In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the John Leonard award for the first book in any genre that has been published in the US in 2017. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard reviews on promising first books.

The John Leonard Prize is our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers. Named for the longtime critic and NBCC co-founder, John Leonard, the prize is awarded for the best first book in any genre. Previous winners include: Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (2013), Phil Klay's Redeployment (2014), Kristin Valdez Quade’s Night at the Fiestas (2015), and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016).

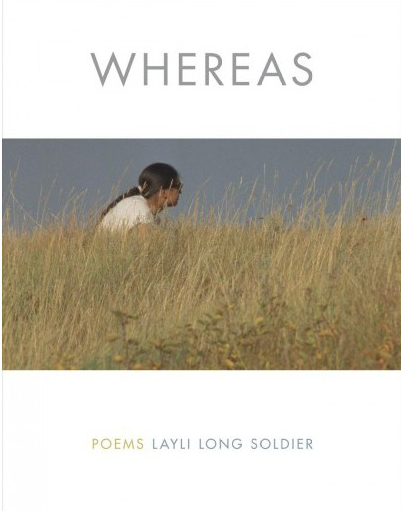

Whereas by Layli Long Soldier. (Graywolf Press). Review by Daisy Fried.

Whereas by Layli Long Soldier. (Graywolf Press). Review by Daisy Fried.

The Oglala Lakota poet and artist Layli Long Soldier writes, she says in her stunning poetry debut Whereas, in “dual citizenship”—tribal and U.S. “In this dual citizenship, I must work, I must eat, I must art, I must mother, I must friend, I must listen, I must observe, constantly I must live.” At the book’s heart are centuries of broken treaties, genocide, non-apologies and non-reparations for crimes by our government against the indigenous tribes. Whereas is also intimately domestic and more than willing to appear autobiographical. Diverse in format—narrative lyrics, legalistic prose, prose poems, concrete poems, lineated confession—the book’s many themes include landscape, identity, grief, loss, birth, death, motherhood, history and oppression. It is also a very good read.

Some particularly scenic moments come early on in “These Being the Concerns,” a sequence that operates partly as Lakota lexicon. The prose poem “Ȟe Sápa” (Lakota for Black Hills, homeland and heartland of broken promises) showcases one of Long Soldier’s dominant sounds: controlled surge, its beauty grounded in fact and description and interrupted by etymology: “Ĥe is a mountain as hé is a horn that comes from a shift in the river, throat to mouth. Followed by sápa, a kind of black sleek in the rise of both.”

Making a different sort of noise, the book’s title sequence takes up its second half. “Whereas” riffs on, interrogates and perhaps attempts to redress the Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans, signed in 2009 by President Barack Obama, read five months later to five tribal leaders (of over 560 federally recognized tribes in the US) then folded into an unrelated piece of defense appropriations legislation. Each of Long Soldier’s own 20+ statements begins with the word “WHEREAS,” as if announcing conditions for a legal resolution, then moves into stories concerning identity, feeling and feeling’s failure, speaking and failing to speak:

“WHEREAS a string-bean blue-eyed man leans back into a swig of beer work-weary lips at the dark bottle keeping cool in short sleeves and khakis he enters the discussion…“Well, at least there was an Apology, that’s all I can say”…Whereas under starlight the fireflies wink across east coast grass I sit there painful in my silence glued to a bench in the midst of the American casual…

Long Soldier’s movement between collective and personal experience makes this book intimate and urgent. “Left” is a standalone lyric about a miscarrying mother. “I self-soothed then/curled to the mattress my eyes splintered tree limbs red tips night window…//at the sign-in window the procedural lady with a computer queried/what’s my home phone cell phone where did I work what’s my address/I’m bleeding I need help now I said then…” After what might be an evocation of the moment of the miscarriage’s completion—”quiet as snow at the mercy us avalanched empty”—the poem cuts to a dream in which the poet finds herself “in a train station bathroom of all places filthy/more stained and stinking wretched by the second,” where she finds a baby she assumes is dead—“but my conscience said hold him.” The dream baby turns out to be alive, covered in sores, horribly deformed. He’s joined by two older brothers. The poem ends

in a train station bathroom I held a forgotten baby left

in a bathroom where no one possibly feels washed

surrounded by three boys

needing a mother I was

their mother in a dream wherein they visited

me in a stanza where we could be nearest each other breathing

the filth they found me in or I would rescue them from—

which in this world is it.

Cleansing here isn’t just a matter of soap and water. A womb “cleanses” itself of a baby. Elsewhere the US has “cleansed” the Lakota and other tribes from their native lands. “How do I wash clean one year later from a dream,” writes Long Soldier. She can hold the dream-baby, will fix it, care for it. But no one in the bathroom is clean, including the mother who has lost a baby and found three sons, all breathing filth and in need of rescue, as the poet-speaker is in need of rescue into fresh motherhood. But if cleansing isn’t necessarily good, then filth isn’t necessarily bad. Is the poet dreaming she would rescue them from filth? Or from cleansing? Can she rescue herself by rescuing them? Is rescue possible? Is remedy impossible?

In the context of Whereas and its histories, this scenario can’t be only personal. When we descend, in this poem, into a dream about miscarriage from which we don’t emerge within the poem, a connection is made—emotionally, symbolically—between individual and collective trauma. That might be this excellent book’s best achievement.

An NBCC Board Member, Daisy Fried is the author of three books of poems, most recently Women's Poetry: Poems and Advice, poetry editor of the political/literary journal Scoundrel Time, and teaches in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers.