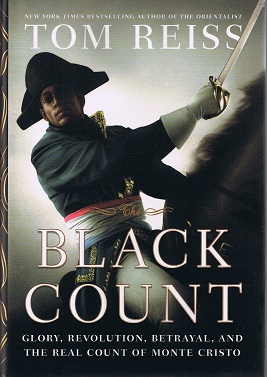

In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member Marcela Valdes offers an appreciation of biography finalist The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (Crown) by Tom Reiss.

Alexandre Dumas was one of those unforgettable men. Dashing. Powerful. Intelligent. Kind. In battle, he performed like a superhero: single-handedly defeating dozens of men. With his wife, he performed like a romantic: writing soulful letters from the front. As a General commanding some 50,000 soldiers, he succeeded where others had failed, and knocked the Austrians off the Alps for France. He was a legend in his own time. He inspired The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Men like Alexandre Dumas are not forgotten — they are wiped out, carefully, by other men.

Alexandre Dumas was one of those unforgettable men. Dashing. Powerful. Intelligent. Kind. In battle, he performed like a superhero: single-handedly defeating dozens of men. With his wife, he performed like a romantic: writing soulful letters from the front. As a General commanding some 50,000 soldiers, he succeeded where others had failed, and knocked the Austrians off the Alps for France. He was a legend in his own time. He inspired The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Men like Alexandre Dumas are not forgotten — they are wiped out, carefully, by other men.

“The life of General Alex Dumas,” Tom Reiss explains, “is so extraordinary on so many levels that it’s easy to forget the most extraordinary thing about it: that it was led by a black man, in a world of whites, at the end of the eighteenth century.” Dumas was born in 1762 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. His mother was a slave, in a place where slaves were considered cheaper than sugar and tens of thousands were gruesomely slaughtered. His father was the brother of a plantation owner; a French aristocrat, he made off with Dumas’s mother and hid for years in the island’s hills.

Even as a boy, Dumas must have been a charmer. For his father sold all his other children into slavery and brought only young Dumas back with him to France. There the marquis dressed his mixed-race son in fashionable silks and sent him to an elite school. When the French Revolution declared all men equal, regardless of color, Dumas was ready. Under the old monarchy he would have had trouble becoming the lowliest of officers. In the new Republic, his courage and talent earned him General-in-Chief of the Army.

Only an ill-fated sea voyage and the venom of Napoleon himself could arrest his sensational career.

Creating The Black Count, Reiss has performed rather like a super-hero himself. Blowing up a safe, hunting down ancient letters, military reports, and newspaper clippings, he has reconstructed the life of a man who has been dead for more than 200 years. With precision and élan, he captures the suspense and vigor of Dumas’s life while also turning it into a study of “the world’s first civil rights movement,” a time at the end of the 18th century when the French Revolution ended both slavery and discrimination based on race. His concise histories of the sugar trade, the Enlightenment, and the French aristocracy tease out the complexities of France’s economic dependance on slaves and its philosophical interest in liberating blacks.

In the end, economics won out. Backed by slave-owning sugar barons, Napoleon eventually seized control of the faltering Republic, keeping a shell democracy even as he shut down newspapers, reinstated slavery, re-segregated the armed forces, and returned to the old royal practice of insisting that all military officers be white.

“As France rejoined the wider world of slaveholding nations,” Reiss writes, “the elevation of nonwhites to positions of power or respect became a dangerous anachronism. In the armies that General Dumas once led, suddenly the very concept of a black soldier commanding white troops was impossible — a black general of division or general-in-chief of an army, unimaginable.”

Dumas had come of age in a time of hope and possibility. His son, the author of The Count of Monte Cristo, grew up impoverished, “in a world of rising, rather than diminishing, racism.” The General himself died despairing, betrayed.

Reiss’s account of Dumas’s betrayal reminds us that racism means not only discrimination, but erasure. And that, at its finest, biography can be a kind of resurrection.

Links:

Tom Reiss' website

Guardian review

Christian Science Monitor review

Washington Post review

New York Times review