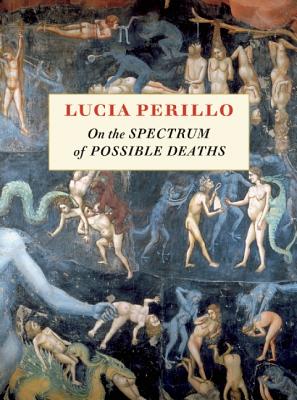

In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member John Reed offers an appreciation of poetry finalist On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths (Copper Canyon Press) by Lucia Perillo.

The personal, the political. The complex, the simple. The tragic, the comic. The culture of the snob, the culture of the noob. Wisdom and doe-eyed naiveté. Those are the dichotomies of good essays, of good prose, of good art, of good living, of good poetry. What's surprising is that Lucia Perillo doesn't bank in any particular duality, nor is there a sense that she has her preferences, that this or that might really be better. Perillo is everywhere. A slate gray boulder, glinting with mica.

The personal, the political. The complex, the simple. The tragic, the comic. The culture of the snob, the culture of the noob. Wisdom and doe-eyed naiveté. Those are the dichotomies of good essays, of good prose, of good art, of good living, of good poetry. What's surprising is that Lucia Perillo doesn't bank in any particular duality, nor is there a sense that she has her preferences, that this or that might really be better. Perillo is everywhere. A slate gray boulder, glinting with mica.

The Pulitzer prize finalist and MacArthur fellow renders her all-in style with staccato precision in On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths, her sixth book of poetry. Mortality—the horror that none of us can quite forget—is both the subject and the subject of the joke in Spectrum, which is as apt to reach out to the reader with a warm hand as a squawk of laughter. “Now my body has become so stylish in the ancient way—didn't Oedipus / also have a bloated foot?”

Perillo ably explores the memory of the body and the mind and the shared experience of those around her. She leaps into her details, or perhaps darts is the better word—moving with sudden stops and turns of direction, maneuvers baffling to aeronautics, but born to the hummingbird. Of course, Perillo's ease is a deception. Adam Plunkett, The New York Times (May, 2012): “The poems in On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths are taut, lucid, lyric, filled with complex emotional reflection while avoiding the usual difficulties of highbrow poetry.”

The literal “spectrum of possible deaths” is too infinite to ponder, and Perillo gestures to the statistical span only in historical terms simultaneously mundane and exceptional. She ticks off a few creeping poisons and abrupt demises in “Aunty Roach,” where one finds a kind of comfort, an understanding that the better part of living is just as flippant, just as irreverent as death. In “Bats,” we find, if not hope, divine distraction in the summersault feedings of the night fliers. In “Black Rider,” we see ” … a boy / skateboarding down the new asphalt of the walk / that he veers off so he can jump / and slide along a tombstone.”

Perillo's is a kind of irresistible amusement—a joy that comes with the backwash at the bottom of the bottle. The bubbles of experience are something uproarious and nauseating, and in that regard all the more uproarious. In “Again, the Body,” Perillo bluntly extolls the dubious virtue of being in skin:

When you spend many hours alone in a room

you have more than the usual chances to disgust yourself—

this is the problem of the body, not that it is mortal

but that it is mortifying. When we were young they taught us

do not touch it, but who can keep from touching it,

from scratching off the juicy scab?

Links:

Lucia Perillo's website