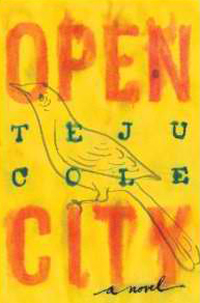

Each day leading up to the March 8 announcement of the 2011 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, in #10 in our series, NBCC board member David Haglund offers an appreciation of fiction finalist Teju Cole's “Open City” (Random House).

“And so when I began to go on evening walks last fall, I found Morningside Heights an easy place from which to set out into the city.” And so Teju Cole sets the mood and the direction of his unusual and beguiling debut novel, Open City—a finalist for the NBCC Award in Fiction this year—right from the start. With that odd “And so” we are immediately in medias res, and in the middle of a life as well—we are even in something like “a dark wood”: These are evening walks, begun in the fall; Open City has something of the dusk about it.

The book’s narrator is a 30-something man from Nigeria named Julius who is in New York on a psychiatry fellowship. He is both highly educated and immensely curious about the world around him; one of the great pleasures of the book is its unabashed intellectualism. On his walks around the city, Julius reflects on the work of artists and composers and philosophers without any of the apologetic irony one might expect to find in a contemporary American novel. Julius is nakedly and intensely interested in rarefied art—painting, opera—and history with a capital H; many extended passages in Open City begin with Julius noting what used to stand at various addresses he passes on his walks. The novel is highly essayistic—even more so than previous NBCC finalist (and winner) Austerlitz, by W.G. Sebald, a writer Cole appears to have learned a great deal from. Cole’s writing is less dreamlike than Sebald’s, more plain; James Wood wrote that the book is “as close to a diary as a novel can get.”

Which is not to say the book lacks its own kind of lyricism. On his walks Julius also thinks about his own past, in Nigeria; he travels to Brussels, where his maternal grandmother lived. Julius’s fascination with both his own past and that of others means that the novel is also partly about death; hence the book’s dusk-like, autumnal mood. Back on that first page Julius tells us that, in addition to his new evening walks, he has begun “watching bird migrations,” a second habit he suspects might be connected to the first. Birds looking down on the people in the city might see something similar, he thinks, to what he sees looking at the birds—small, vital creatures flitting about, the skyscrapers “like firs massed in a grove.”

And on the last pages of the novel Julius impulsively boards a boat at Chelsea Piers, one that traces “a fast arc south,” so that “the taller buildings in the Wall Street area” soon loom into view. And there’s the Statue of Liberty, the crown of which, Julius says, has remained closed since late 2001. The statue has always, of course, been a symbol of migration to the U.S.; until 1902, it was also, Julius notes, a working lighthouse, one that both “guided ships into Manhattan’s harbor” and “fatally disoriented birds,” which would crash into it and die in dozens and even hundreds—huge numbers of birds falling at the statue’s feet, eventually to be collected for the uncertain and imperfect purposes of science. With these dying birds the novel ends, closing Julius’s own, somewhat melancholy arc through a city and a decade shadowed by death and the past.