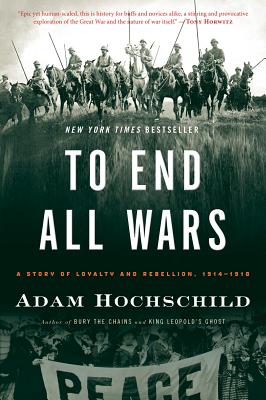

Each day leading up to the March 8 announcement of the 2011 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, in #16 of our series, a nonfiction finalist, Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) reviewed here by NBCC board member Karen Long.

Reading “To End All Wars” calls to mind the playground.

Reading “To End All Wars” calls to mind the playground.

In this charged, lucid account of the First World War, we watch generals and politicians reach for techniques common to any middle-school brawl: catcalls, face-saving, paeans to honor, appeals to manliness, cries to God and gleeful maneuvering so as to be able to say, “He started it.”

Celebrities stoke the hostilities, like boys circling the fray. Thomas Mann, Germany's greatest living writer, declared the coming war meant “purification, liberation” from the “toxic comfort of peace.” Just as bellicose was Rudyard Kipling, whose writing characterized the nasty British aggression in the Boer War as a foretaste, “a first-class dress-parade for Armageddon.”

Nearly a century after World War I, the truism remains — the war was folly — yet the scale remains difficult to grasp. The indispensable Adam Hochschild has a way with telling detail, including this one: “If the British dead alone were to rise up and march 24 hours a day past a given spot, four abreast, it would take them more than two and a half days.”

And still, the civilian toll – an estimated 12 million to 13 million dead – was higher than the military's. The war ignited famine and seeded the Armenian genocide. Hochschild, in his signature way, also notes what few governments bothered to count: the deaths of 400,000 underfed, whipped African porters along the Western front.

The writer begins by walking the northern French countryside, stopping in hundreds of cemeteries, reading markers and visitor's logs. Here, the gunners' ears bled from the concussive noise and the farmland is still pitted and gouged. Here, too, passers-by still trigger unexploded shells – 31 such deaths in 1991 alone.

Hochschild has written two classic books: “King Leopold's Ghost,” about forced labor and murder in the Congo; and “Bury the Chains,” about England shedding its slave trade. A founder of Mother Jones magazine, he has long been a keen and eloquent student of how cultural consensus is reached, resisted and remade.

It helps that his writing is as clear as a church bell. Hochschild describes the obstinate prosecution of Europe's first industrial war and the patchy resistance to that conflict, mostly in England, where some 20,000 men defied the draft. Roughly 6,000 conscientious objectors went to prison; some were executed.

Fifty were handcuffed, transported to France and informed, a few days before the Battle of the Somme, they would be executed if they refused to fight.

“In an act of great collective courage . . . not a single man wavered,” Hochschild writes. “Only at the last minute, thanks to frantic lobbying in London, were their lives saved. These resisters and their comrades did not come close to stopping the war, and have won no place in the standard history books, but their strength of conviction remains one of the glories of a dark time.”

Hochschild follows the stories of a handful of such individuals, including the anti-war crusader Charlotte Despard, whose brother commanded the British forces in Europe, and Albert Rochester, a railway signalman court-marshaled for his temerity in questioning why every English officer kept a personal servant to polish his boots.

At trial, Rochester was as withering as the era's most celebrated resister, Bertrand Russell.

“This war is trivial, for all its vastness,” wrote the mathematician, who was also prosecuted and jailed. “No great principle is at stake, no great human purpose is involved on either side. . . . The English and French say they are fighting in defence of democracy, but they do not wish their words to be heard in Petrograd or Calcutta.”

Questions of patriotism and morality sting along these pages, which chronicle the lethal advent of tank warfare, chlorine gas and German women so hungry they tear apart a faltering horse. Kipling, we learn, rushed his only son into uniform at age 17, pulling strings to have the boy's myopia overlooked.

A shell fragment in Belgium shattered John Kipling's mouth. He was last seen crying in pain; his body was never found. No one dared tell his formidable father, who imagined his son's last act as laughing at some soldierly jest. Still, when an American friend came to visit the imperialist poet, he squeezed her hand hard and said, “Down on your knees, Julia, and thank God you haven't a son.”

Such scenes cut us and underscore Hochschild's fairness and empathy. Many books about World War I crowd the shelves; more will arrive to mark its centennial in two years. Here is one to give pause to the United States, still at war, still trying to discern its own purpose in arms.

Idealists all around fought in and resisted the Great War, and, as Hochschild shows, all that sacrifice, all those rivers of blood, changed the world for the worse.