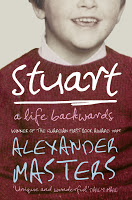

Today's posts will focus on “Stuart: A Life Backwards” by Alexander Masters (Delacorte Press), which is a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award for memoir.

Today's posts will focus on “Stuart: A Life Backwards” by Alexander Masters (Delacorte Press), which is a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award for memoir.

“Stuart: A Life Backwards” defies categorization. Mark Haddon, author of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” called it “possibly the best biography I have ever read.” The Sunday Times referred to it as “gripping,” usually a word reserved for suspense novels. The London Review of Books called it “hilarious,” suggesting a comedy. And these are just from blurbs from the book’s cover. No wonder the NBCC Board had so much difficult in deciding which award category “Stuart” belonged in before finally nominating it for the NBCC Autobiography/Memoir Award.

One thing we knew for certain: “Stuart: A Life Backwards” was not fiction. If only Alexander Masters were describing an imagined world rather than the harsh and at times terrifying reality of the homeless. Drug addicts, alcoholics or just people down on their luck, the people of the street are all too real, no matter how often we avert our eyes.

But categorizing this book as a depressing expose of life on the streets, a sociological study of how people end up homeless doesn’t work for “Stuart” either. Plenty in “Stuart” is disheartening, especially the part about how society has failed so many of its most vulnerable, but the book also is quirky, highly personable and, yes, hilarious.

So “Stuart” is neither fiction nor dispassionate nonfiction. Nor is it straightforward biography — and not only because Masters, on the advice of Stuart himself, tells the story of the ex-junkie’s life “backwards,” beginning with his present-day mess of a life and tracing back to the smiling 13-year-old Stuart Shorter so we can see “what murdered the boy I was,” as Stuart puts it. For Masters is not just writing about the life of a particular homeless man – he’s also writing about his own life among the homeless and of the improbable friendship that arose between himself and Stuart.

Yes, friendship. A transplanted New Yorker, Masters went to England to study physics and mathematics and ended up working at a hostel for the homeless and running a street newspaper. The improbable fact that he found a true friendship with a member of what he refers to as the “chaotic” homeless, “the worst face of homelessness, and when not the most hateful, the most pitiable extremity of street life,” is nearly a miracle. And it is what makes this book so unique. Masters tells us the story of Stuart and his exasperation with this knife-wielding, psychopathic alcoholic in a genuinely funny and disarmingly honest way. The way you would describe a much beloved friend. And that is just what Stuart was to Masters. Masters bonds with the maddeningly complex and strangely engaging Stuart. He gets us to bond with him, too, making it just that much harder for us to avert our eyes the next time we pass someone who is homeless.