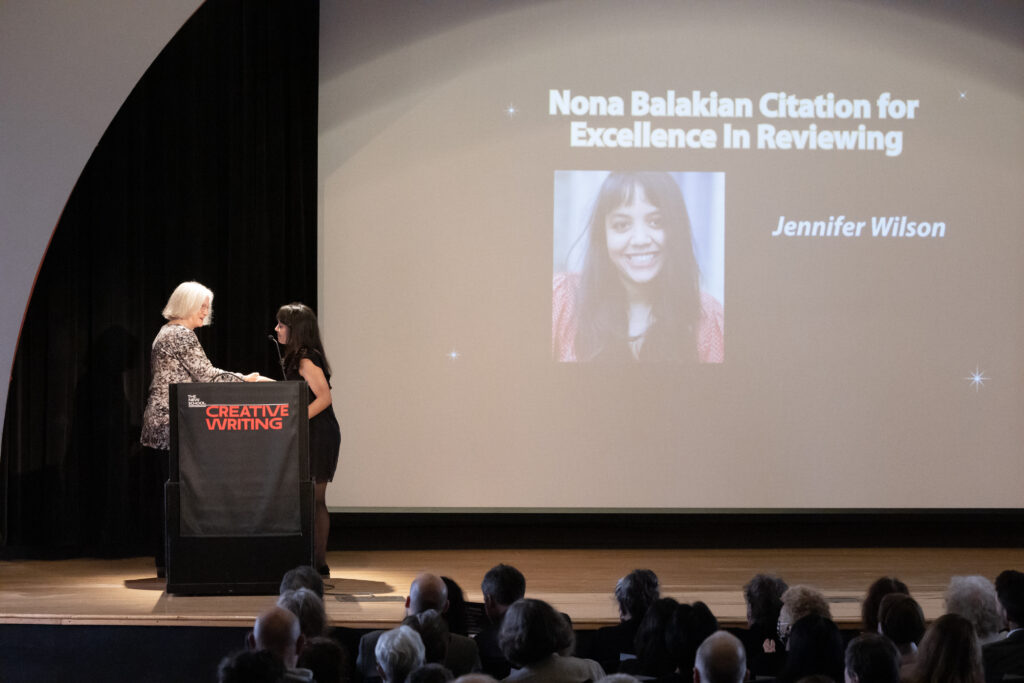

The Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing is awarded each year to honor exceptional work by a member of the NBCC. The 2022 recipient of the Balakian Prize is Jennifer Wilson, a contributing writer at The Nation and a contributing essayist at The New York Times. She teaches arts and culture reporting at the Craig J. Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. She is also currently working on a novel about sanctions.

Your pieces span a number of different forms. Some comment on current affairs through literature, others revisit classics from the past, and yet others analyze recent literary trends. And of course, there are also focused reviews of new books. How do you decide what to write about? How do you choose which books to focus on?

For me, the best part of book reviewing is that you get to essentially write about everything. I’ve reviewed books on Soviet soil science, Chilean poetry, divorce in the Gilded Age. I see each book as the opportunity to become fully enmeshed in a world previously unknown to me. So I tend to choose books that feel like little adventures. I do a lot of outside reading for my reviews, so I’ll see a book and get excited, thinking—yes this would let me spend the next few weeks fully absorbed in African American crime fiction or the 2020 protests in Belarus. I feel the same way about reporting. It’s very much about how I want to spend my time, which is another way of saying it’s about how I want to spend my life.

How do you conceive of the role of contemporary literary criticism?

Well, I do think it should strive to feel “contemporary.” Writers live in a society, and I truly believe every author has something they want to say about that society, sometimes it’s a specific argument, sometimes it’s a declaration of confusion or frustration about not being able to arrive at one. As a critic, I try to identify what an author is trying to communicate about the culture we live in. To me, a good book sharpens our view of the world, pushes us to think more deeply and complexly about our surroundings, and does that not only through plot but through style. A book that can elevate the conversation while elevating the form is what excites me most as a critic.

It feels like the field of Slavic Studies is in a moment of reckoning right now, as we approach the one-year mark of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, in general, increasing interest in race, coloniality, gender, and sexuality across the university. One flashpoint I have in mind is Elif Batuman’s recent essay in the New Yorker, which was a point of contention at a recent talk I attended at the Slavic Studies department at Harvard. Of course, you’ve been thinking about the intersections of Russian literature, race, and sexuality way before this (you did so in your earliest pieces, which date back to 2016). What has it been like watching all of this unfold?

I definitely felt like when I tried to broach these subjects in academia, especially as a Black woman, people would get defensive like– “oh look here comes the woke brigade.” I remember someone accused me of trying to “cancel” Gogol, which is hilarious to me on so many different levels, not least of which is that Gogol cancelled himself (he burned the second volume of Dead Souls). So I very much appreciated that Elif laid out the colonial context in such a clear, unambiguous way, and I think she, as someone who has written so warmly about these very beloved (including by me) novels, made her a great messenger for this much-needed critique. I know there’s been some quibbling over the details, but that’s part of the fun of academia, occasionally arguing over things that don’t really matter.

Not having been there, I can’t speak to the specific objections, but I know it’s been a tricky moment for Slavic academia. The field was essentially built by people who fled the Soviet Union, where for long periods of time literary criticism amounted to digging up charismatic characters from the 19th century canon and explaining how they were actually proto-Bolsheviks. Understandably, these scholars saw disengaging from political readings of literature as a form of protest, and I think that legacy persists. Literary studies also has not been immune from Soviet whataboutism. I definitely remember emailing a professor an interesting article about the Sochi Olympics and Russian colonization of the Caucasus. He wrote back “informing” me that the U.S. Open is played on Native American land. And yes, that’s also true, but one doesn’t cancel out the other. One is connected to the other.

I fully support calls to integrate postcolonialism into Slavic curricula, but I do worry about what it means for this to be happening during a war. I’ve seen some colleagues suddenly start talking about Russian culture as an aggressor culture, which only really bothers me because of how it seems to be placing countries that support Ukraine on a moral high ground that they haven’t earned. Also, it’s just made for bad literary criticism. We all got into this massive fight on Facebook over Oksana Zabuzhko’s essay for TLS in which she argues that Russian literature has been training Western readers to see “imperviousness to evil as a virtue.” She cites Tolstoy’s sympathy for Natasha Rostova after she betrays her fiancé with Anatole Kuragin. This I could not support. I joined the side who objected to this reading. I believe you can stand with Ukraine and stand with Natasha’s libido. That’s the world I want to live in anyway.

The trend in Slavic Studies might be mapped onto a broader cultural conversation about what to do about “the classics” or “the canon.” To be honest, I don’t find this debate (i.e., “the canon is just all dead white men” vs. some inanity about cancel culture) all that scintillating, but I suspect you might have a thoughtful take on all this, given that you’ve written extensively about “the classics,” but always in challenging and creative ways. What do you wish people were paying more attention to in this discourse?

In terms of the canon, I think all of us, including those of us who research 19th-century Russian literature, want people to read beyond Tolstoyevsky. There’s a very interesting working group right now, “The Other 19v” which my friend Helen Stuhr-Rommereim helped start, which looks at minor, non-canonical figures from the so-called Golden Age of Russian Literature. These include writers from outside the nobility. Considering that nobles were required to perform imperial service in Russia, it does strike me as important to think about decanonization and decolonization in the same breath. The problem is that Slavic departments are worried these classes won’t attract the same number of students, and that a drop in enrollments could affect funding, the number of tenure-track lines, or worse (I’ve seen Slavic departments shut down entirely). So, U.S. political life, specifically the defunding of higher education, is also an important context here.

What is your book reviewing process?

Oh god. Well, I will say it depends on the outlet I’m writing for because there’s a different process when you have 600 words versus when you have 4,000. Like everyone else, I go back and read the writer’s previous books. That’s not always possible though; for instance, I have not read all twenty-three of Percival Everett’s novels. I would like to though; he’d make for a really great season of the Mr. Difficult podcast. If it’s nonfiction, you want to read other books on the subject, so you have something to compare this book to. Long-form reviews are a different beast entirely. In that case, you sometimes are doing original research, going back and filling in what a nonfiction writer didn’t attend to in their book. That’s not always a fault of the book; academic books aren’t supposed to be focusing on how they can make a subject really pop for non-specialists, but you as a critic writing for magazines do have to think about this. I even had an author tell me once how much they learned from my review of their book! I don’t think this is unique to me by the way. Every critic I talk to puts in this amount of work or more. It’s very labor intensive.

(If you’re willing to say anything on this, but no pressure) How do you make book reviewing work as a career (that is to say, financially)?

You know, I don’t. Last year was the first year where I really tried to make it happen, and I was so depleted by the end, I decided this year, I’ll focus on writing cover letters instead. In 2022, I wrote twenty-two pieces, many of which were quite long, because otherwise, I wouldn’t have made enough money to get by. And I’m lucky because I have health insurance through my partner, and I mostly write for print now, which pays better. I also adjunct (I teach journalism at CUNY). I’ve been doing some work with the Freelance Solidarity Project (FSP) to try to raise rates across the industry for book reviewers, because like I said above, it’s very labor intensive and too often critics feel like they’re sacrificing their own well-being and financial position to do the amount of work required.

Do you have any predictions for upcoming literary trends? What are you most excited to read this year?

Honestly, I hope there aren’t any trends. I want to be surprised over and over. I’m really craving books with big stages, books that feel ravenous for scale. I’m extremely excited for Lydia Kiesling’s new novel, Mobility; it’s about an American teenager growing up in Azerbaijan who has a front frow seat to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the War on Terror. I’m also looking forward to Sylvia Aguilar Zéleny’s Trash (translated by J.D. Pluecker); it’s about three women—an orphan, a scientist, and a sex worker—whose lives are all entangled with a garbage dump in Ciudad Juárez. And of course, the new Zadie Smith has me so excited I can barely sit still. She’s my vote for greatest living novelist in the English language.

Kathy Chow is a literary critic, an assistant editor at The Yale Review, and a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Yale University. She holds an MTh in Systematic Theology with Distinction from the University of Edinburgh and an A.B., magna cum laude from Princeton University, where she studied political theory. She is currently based in Cambridge, MA.

The 2022 National Book Critics Circle Awards, New School Auditorium, New York, New York, March 23, 2023. Photograph by Beowulf Sheehan

The 2022 National Book Critics Circle Awards, New School Auditorium, New York, New York, March 23, 2023. Photograph by Beowulf Sheehan