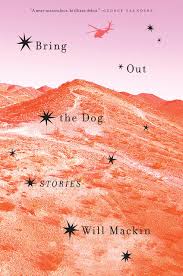

The John Leonard Prize, our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers, is awarded for the best first book in any genre. In advance of the announcement, we're inviting members to contribute appreciations of titles under consideration. (If you're interested in doing so, please email nbcccritics@gmail.com with the subject line Leonard.) Below, NBCC member Brendan Driscoll writes on Will Mackin's story collection “Bring Out the Dog” (Random House).

One of the recurrent visuals in Will Mackin’s debut collection of war stories, Bring Out the Dog, is something called “sparkle.” The narrator of “Yankee Two,” a brutal glimpse of a couple “bad nights” had by some Navy SEALs in Iraq, explains:

One of the recurrent visuals in Will Mackin’s debut collection of war stories, Bring Out the Dog, is something called “sparkle.” The narrator of “Yankee Two,” a brutal glimpse of a couple “bad nights” had by some Navy SEALs in Iraq, explains:

We each had a device mounted to our rifles that generated sparkle–i.e., an infrared spotlight with a laser at its center. We used it to illuminate targets, and see into dark places we otherwise couldn’t. Bobby’s infrared spotlight, for example, brightened the depths of the storm drain.

Together with night-vision technology, sparkle allows the SEALs a mostly invisible means of navigating their surroundings and thus a tactical advantage in combat. It also serves as a silent means of communication; a means of collective reassurance amidst dicey circumstances; a pushing back, however ephemeral, against the darkness.

Bobby stopped sparkling the storm drain and continued walking up the street. Lou, not even limping, stepped off behind Bobby…Then, all at once: Lou sparkled a pile of trash; Zsa-Zsa sparkled a bedsheet hanging from a rooftop clothesline; and Tull sparkled a ground-floor window, making it surge like a portal to another dimension.

“This ain’t Dark Side of the fuckin’ Moon laser light show!” Spot radioed, and all the sparkles went dark.

Sparkle is a real thing, of course, just like cell-phone signal triangulation and holographic rifle sights and laser-directed remote air attacks and all of the other technological means of warfare that figure prominently in Mackin’s narratives. But, in a book in which so much takes place in the dark, all of this sparkling also functions symbolically, to underscore one of Mackin’s recurrent themes: the yearning for clarity and perspective within the dissociative, surreal experience of contemporary war. Our uneasy SEAL team may be the ones sloppily toggling sparkle everywhere as they go house-by-house in Iraq, haunted by the memory of a recent near-miss. But each story in the collection, even those set stateside, in Utah bombing ranges or in cheap North Carolina motels, reiterates that war equals confusion; alienation; the inability to see things–most of all, one’s self–accurately.

Sometimes the infrared light helps. But sometimes sparkle leads to distortion; muddle; a potentially deadly compounding of fear:

Now Hit was shaping up to be something of a milk run. Or so I thought until I saw the infrared waves, in Bobby’s sparkle, reversed. Did waves diverging from the laser mean that we were fucked? Or was it waves converging, à la Qa’im? It could have been so much worse.

One of Mackin’s many talents is his ability to communicate the weird concentration of experience that characterizes war with such economy of language. The majority of his words are dedicated to describing technical items, like infrared scopes, or explanations of the ways and means of SEALs. The emotion, however, is never far away. When it emerges it feels like an ambush. But oh, how beautifully it sparkles.

Brendan Driscoll's work has appeared in Booklist, The Millions, and other periodicals. He is writing a novel about food, love and immigration status. Originally from western New York State, he now lives in Colorado.