What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launched this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, Convenience Store Woman, or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, The World of Yesterday.'The deadline is August 3, 2018. Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

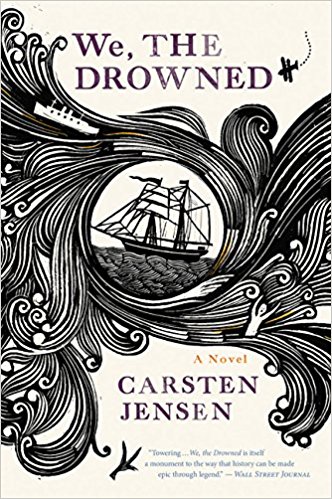

From the first line onwards, Carsten Jensen’s seafaring epic, We, the Drowned (tr. Charlotte Barslund and Emma Ryder), is a magnificent combination of history and legend: “Many years ago there lived a man called Laurids Madsen, who went up to heaven and came down again thanks to his boots.” Jensen traces the history of Marstal, a small island off the coast of Denmark, across nearly two centuries of war, peace and maritime adventure, starting with conflict with the Germans in the 1850s and continuing through to the aftermath of World War II. Over the decades readers meet four generations of fathers and sons, whose journeys reflect the island’s dependence on the sea. The book has many identifiable influences, from Homer to Heart of Darkness via Robinson Crusoe, and, though it is a translation from the Danish, its 700 pages read as fluently as any English-language text.

While the novel also includes first-person and third-person omniscient sections, the predominant use of the first-person plural is particularly clever because the identity of the narrating group shifts as the story progresses: first it is Marstallers generally, then schoolboy peers, and later the widows left behind on the island. Having this mutable body of observers – almost like the chorus in a Greek myth – allows Jensen to show every situation from the inside, but also to introduce occasional doubt about what has happened. An example is the slyly postmodern chapter following a central character’s death: “We don’t know if that’s how it actually happened. We don’t know what [he] thought or did in his final hours. …We don’t really know anything, and we each have our own version of the story.” It’s that blend of ancient epic-style storytelling and fresh perspective that makes this book so enthralling.