For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

Carmen Maria Machado’s writing considers the individual. Within her words the reader finds new questions—and answers are found sprinkled throughout the text, sometimes in the most unexpected places.

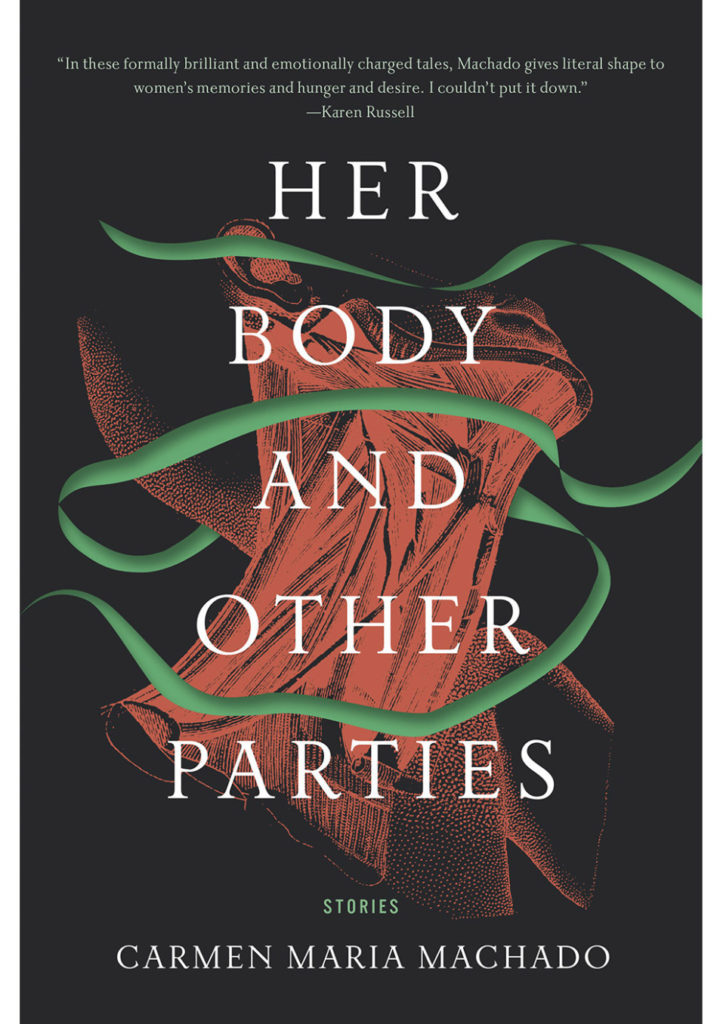

Recipient of the National Book Critic Circle Award’s John Leonard Prize for debut fiction, Her Body and Other Parties (Graywolf), is a story collection rich in femininity, identity, uncovering trauma and independence. Machado’s sentences are lyrical, often poetic but never indirect. Her imagery is surprising, but in the same moment, intensely recognizable.

From her home in Philadelphia, Machado spoke with The New School MFA student, Wynne Kontos about grieving turkeys, the female experience and staying strong as a new writer.

Do you remember some of the earliest stories you ever wrote?

I wrote a lot of poems, very dramatic essays and short stories. Of course I use these terms very loosely. The one I remember most clearly is a book I wrote on my father’s stationery called, “The Biggest Turkey Can’t Find the Farm.” It’s about a turkey who’s lost and trying to get home. At the very end he gets to the farm, and the final page is a roast turkey on a plate that says, “I wish I did not come here.”

My parents were really disturbed, but I was very interested in this darkness. It’s weird when I look back at stories I wrote as a kid because I have the same interests. It’s all about death and illness and sadness—all the same things. I’m just a better writer now.

The stories in this collection have recognizable bits of our world, but often include a twist. What was it like workshopping pieces like this? Have you ever received pushback from peers or editors to more clearly define the ethereal aspects of your writing?

Mostly, no. The only time someone responded super negatively was when I workshopped “Especially Heinous.” One classmate loathed it and wrote me a very mean and angry letter. [Other than that] my workshop experience was really positive and I felt really supported with my projects.

What about in the publishing process?

I struggled to publish certain stories. For instance “Especially Heinous” took me a long time to sell. The biggest sort of obstacle I faced was that they were short stories. It wasn’t about world building, or experimentation. I’m really lucky I’ve been able to find a publisher, an agent and people who took a risk with my work.

What is some writing advice that you applied to this collection?

My beloved teacher Michelle Huneven, who was one of my teachers at Iowa, gave me a really hard time about my sentences. She was like, “Your sentences are almost good, but you’re getting lazy about them. You really need to sit on them—work on your sentences.” That became something I really kept in mind, and was on my mind as I was writing and editing.

How do you “sit on your sentences?”

I had to spend more time with them and not forget them. There were things I was sort of doing, that now I do all the time, like read my sentences out loud for example. Really thinking about each sentence and what it’s doing and not thinking of them as secondary. They become a really important way to get into a piece of writing.

So much of the female experience is rooted in mental or physical pain, and your writing captures that in such detail. In “Bad At Parties” a woman lives with the aftermath of physical trauma, in “The Husband Stitch” you write about childbirth and the sexualization of an episiotomy procedure. But then we have “Inventory” or “Eight Bites,” which begin with the lead character’s discomfort. While physical pain is often part of the female condition, there’s also the reality of just—discomfort, and your characters experience this too. From these types of pain or discomfort your characters often find strength rooted in their experiences. Can you talk more about why you’re compelled to explore these concepts in your work?

That’s a really good question. I feel like pain and suffering, whether it’s physical or not, is a sort of thing you have to work around. You won’t be able to get where you need to go. That place is very interesting for me as a writer, and that comes from my own life and feelings about being a woman in the world.

The novella in this collection, “Especially Heinous,” is 272 imagined synopses of Law and Order: SVU episodes. There were several moments of humor, but this piece also reminded me how discomfiting it is to admit I’m a long time viewer of this program. It’s a show that tries to draw attention to issues around sexual assault and abuse, but it’s still using those traumas to entertain us. Is this novella a commentary of any kind?

I think it’s a combination of a love letter to, and a critique of, a show I watch and have a lot of feelings about. The show itself is an interesting way to examine narratives about sexual assault and how they play out and how we consume them. It’s relevant to me that the only currently running Law and Order franchise is the rape one. But it has this real staying power that has outlived every other version.

I was recently re-watching some old episodes of Law and Order: SVU, and it’s so much better than the new stuff. The early SVU is actually pretty solid in a lot of ways, and I was kind of admiring how decent it was in an aesthetic sense. But [the novella is] a critique and a perfect lens to discuss this issue, it’s sort of weird how perfect it is. The novella gave me the space to talk about the things I feel strongly about which is the narrative of sexual violence and also what it feels like to binge watch something on Netflix.

A favorite part of this collection for me is the conversations with other women that it inspired. There’s something extraordinary about reading powerful work about women, but also something overwhelming about identifying these common experiences we share. Why do you think that is?

Everybody sort of knows that feeling of someone saying a thing and you think, “I thought I only felt that thing.” It’s this shock of being recognized and the intensity of realizing the shared experience is a highlight of the trauma. [It can] feel like it’s a lot of pieces have fallen into place and can be a very uncomfortable experience.

I think that’s the reason the story “Cat Person” went viral because it’s a sudden moment of common recognition of a very specific, very relatable scenario that felt very familiar to a lot of women—this very varied sort of trauma that’s hard to talk about it, which in that case is technical consent, when you just feel like you can’t be bothered, or you can’t say no because it’s too much of a hassle.

What does your ideal writing day look like?

I’m not at home. I’m somewhere in the wilderness, away from my whole life. I don’t write very well at home. I kind of need to be elsewhere. I write in my apartment or little coffee shops, but I prefer residencies.

When I’m at home, there’s always something to clean, always something to do. I want to wake up really early and have coffee, have a little bit of breakfast and just write until noon and then read or hike for the rest of the day and then go to bed super early. That’s my ideal writing day.

What can you tell us about your upcoming memoir, House in Indiana?

Because it is still very much a thing in flux, I can’t talk about it too much, but what I can say is it’s an experimentally structured memoir about physical abuse in same-sex relationships, trauma and narratives of trauma—and probably other stuff too.

What are some things you wished you’d known while you were in your MFA program?

I would’ve said, “Calm down it’s going to be okay.” I was figuring out who I was as an artist and was very anxious about performing in a certain way. The agents who visited Iowa would tell me, “It’s very hard to sell short stories! Call me when you have a novel!” I’d feel very dejected and despondent. [Other writers] were getting picked up left and right and I was sort of like sad George Michael from Arrested Development thinking, “I’m never going to get picked up, no one’s going to want me!”

Every teacher I had, even Lan Samantha Chang said, “just make good art, take the time, don’t get to overly worked up about the professional stuff, it’ll all work out. Just try to work on your work.” I always felt like, easy for you to say, famous writer!

But it’s true. All the other stuff will fall into place. I would try to get myself to be a little less anxious about the professional stuff, honestly. It’s fine and it all works out.

That’s lovely to hear. All writers can do it; we’re going to survive!

Yes! Just make good art, everything else will fall into place. But you’ve got to make good art.

Is there anything you feel would be good for emerging writers to know?

You don’t have to live in New York to be a writer. People always say that and I don’t think it’s true. You have to keep reading, because when you read a really good book, story or essay it’ll remind you why you want to be writing.

Photo Credit: Art Streiber