In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the John Leonard award for the first book in any genre that has been published in the US in 2017. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard reviews on promising first books.

The John Leonard Prize is our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers. Named for the longtime critic and NBCC co-founder, John Leonard, the prize is awarded for the best first book in any genre. Previous winners include: Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (2013), Phil Klay's Redeployment (2014), Kristin Valdez Quade’s Night at the Fiestas (2015), and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016).

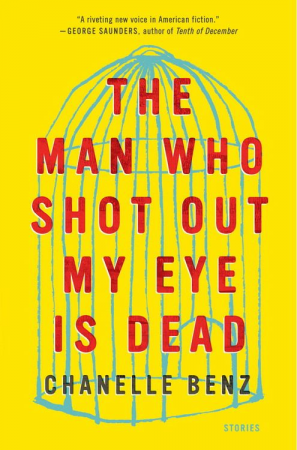

This impressive debut short story collection by Chanelle Benz consists of ten stories that move fluidly through time and place. We begin with “West of the Known,” a 19th century western tale about a woman and her half-brother, and we end with “That We May Be All One Sheepefolde,” a story about a 16th century monk. In between we visit, among other locations, contemporary Philadelphia, the Kalahari Desert in 2001, and Arkansas in the 1930’s. Each story is deeply rooted in its setting, and there are moments when it seems unlikely that the same writer penned such different narratives. And yet the themes of rage, violence, and loss as well as the always strong and often moving prose show us that these stories are, in fact, tightly linked.

This impressive debut short story collection by Chanelle Benz consists of ten stories that move fluidly through time and place. We begin with “West of the Known,” a 19th century western tale about a woman and her half-brother, and we end with “That We May Be All One Sheepefolde,” a story about a 16th century monk. In between we visit, among other locations, contemporary Philadelphia, the Kalahari Desert in 2001, and Arkansas in the 1930’s. Each story is deeply rooted in its setting, and there are moments when it seems unlikely that the same writer penned such different narratives. And yet the themes of rage, violence, and loss as well as the always strong and often moving prose show us that these stories are, in fact, tightly linked.

At times, the collection is reminiscent of John Keene’s wonderful collection Counternarratives. Both Keene and Benz are interested in examining the lives of those whose stories have not been told and in doing so across time. But while Counternarratives is primarily concerned with retelling stories of race and slavery, Benz’s collection is equally interested in gender and class. Its movement through time is also more jarring. Once we get used to the rhythm of the book, though, it’s part of its great appeal: Where will the next story take us? What can we learn from the sequencing of the stories? How does the present reflect the past?

In lesser-skilled hands, this collection might feel gimmicky: here’s a story about the Wild West! A spy story! The handwritten confession of a murder! But it is precisely the examination and the rewriting of these traditional narratives that gives them their power. Benz knows how to get at the heart of her characters, how to explore the human condition no matter the time or the setting. In each story, I found myself initially aware of and in awe of the prose, but as the stories progressed, I got so drawn into them that I became part of their world.

“The Mourners,” which takes place in 1889, follows Emmeline, a black woman who has recently lost her white husband as well as two of her three sons. In the early days following her husband’s death, we feel Emmeline’s deep grief and pain as well as the love for her remaining son: “Only Judah, squirming on her lap, could slip under and touch, his fingers reminding her with their hot wet that though no longer a wife, she must be a mother.” In “James III,” the ninth-grade protagonist is running away from an abusive step-father and goes to visit his father in jail: “But when I opened my mouth there was a God-robbing crack in my chest and I knew that my life was not ever gonna come correct.” And in “Snake Doctors,” two twins, Robert and Izabel, tell the story of the days after their mother’s death, Izabel recounting “So I breathed in Robert and the horses and a world that didn’t have my mother in it.” Again and again, loss lies at the center, and Benz finds new and moving ways to describe it.

Violence and rage, too, are found throughout. In “West of the Known,” a woman is being abused by her cousin:

Always I heard his step before the door and I knew when it was not the walking by kind. I would not move from the moment my cousin came in, till the moment he went out, from when he took down my nightdress, till I returned to myself to find how poorly the cream bow at my neck had been tied.

There is something intentionally disquieting about the fact that violence is often portrayed here in stunning prose. Benz seems to be saying that not only is violence a necessary part of life but that part of being human is to understand our attraction to it. This collection shows us, again and again, that loss, death, and violence are at the heart of the human experience, shared by us all.