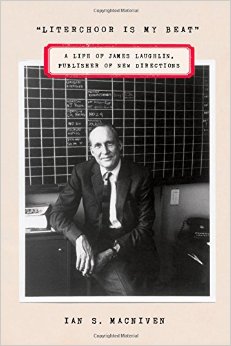

In the weeks leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Kate Tuttle offers an appreciation of biography finalist Ian S. MacNiven's “Literchoor Is My Beat” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

As founder of the publishing house New Directions, James Laughlin wielded enormous influence over midcentury literary culture, bringing out books by everyone from Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams to Herman Hesse and Thomas Merton. In addition to his role as an editor, Laughlin was also a poet – albeit one plagued by self-doubt – and an athlete, whose lifelong love of skiing led him to found a ski lodge in Alta, Utah, which he owned and helped run for many years. Although his was never a household name, in Ian S. MacNiven’s biography we can begin to understand what a central, indispensible figure Laughlin was.

Born in 1914 into a wealthy Pittsburgh steel family, Laughlin was a “shy, clinging, and rather delicate” [13] child, MacNiven writes, close to his father and afraid of his strict Presbyterian mother. He fell for modern literature at Choate, prompting a row with his mother, who was so unnerved by a passage from his copy of T. S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” that she “wept and prayed over him.” While a student at Harvard, Laughlin managed to spend summers in Europe, meeting Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound, who would become his lifelong friend, teacher, and albatross.

Although Laughlin never lacked for romantic love – starting but not ending with his three marriages – it’s his relationships with his writers that occupy the heart of this biography. Pound was the first and deepest influence; schooling Laughlin in modernism at what he called “the Ezuversity,” one-on-one lectures delivered over food and wine or during long walks near Pound’s Mediterranean villa in Rapallo. If Pounds ideas were at times vexing – Laughlin once called the process “education by provocation” – it was through the elder poet that Laughlin explored and expanded the sensibility that would make him a great publisher.

Laughlin founded New Directions while still an undergraduate, publishing his “New Directions in Poetry and Prose” in 1936. Its contents included work by Stein, Pound, Wallace Stevens, Elizabeth Bishop, Marianne Moore, Jean Cocteau, and E. E. Cummings. Over the next several decades, Laughlin was so successful at spotting and nurturing talent that he saw many of his most successful writers, including Nabokov and Williams, scooped up by bigger presses. Still, he maintained rich friendships with most, loaned money to many of them, and paid for Delmore Schwartz’s psychiatric care. “Once a person had entered J’s good books,” MacNiven writes, “he would put up with almost anything.”

MacNiven’s portrait of Laughlin is equally generous: clear-eyed, yet affectionate. Making great use of the trove of letters posted among the publisher and his writers, his wives, his other family and friends, writing with particular sensitivity about his fears of inheriting his father’s bipolar disorder, his literary insecurity, and his knack for falling in love with too many women at once. In the end, Laughlin emerges as a man of enormous vitality and vulnerability, brilliance and self-doubt – a fascinating individual, and also, of course, a man of his times.

Other reviews: