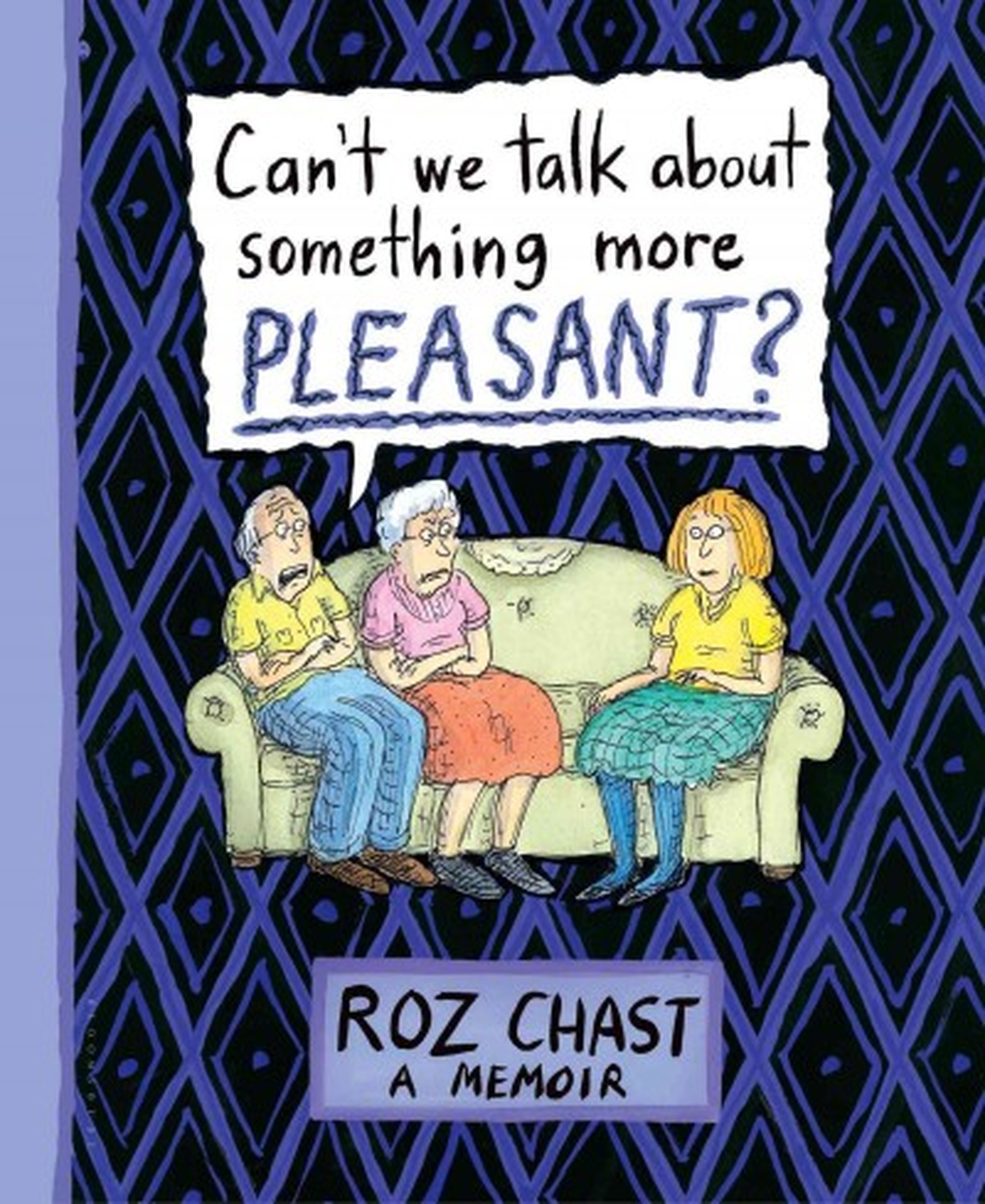

In the weeks leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Eric Liebetrau offers an appreciation of autobiography finalist Roz Chast's “Can't We Talk about Something More Pleasant” (Bloomsbury).

Caring for aging parents is a difficult, frustrating, messy, expensive, and time-consuming proposition, utterly exhausting on every level. While a parent’s physical decline is tough to handle—the aches, pains, declining hearing and vision—the mental erosion is often the most heartbreaking aspect of the endeavor. To watch someone you love slowly fade out of their essential character is one of life’s cruelest struggles.

In the early 2000s, beloved New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast began to experience all of these feelings and more. In her revelatory, pitch-perfect and—yes—often-hilarious graphic memoir of that time, she masterfully captures the kaleidoscopic array of emotions involved in the caregiving for her 90-something parents. The author’s trademark style—a distinct blend of wry gallows humor and heightened awareness of her own, and others’, idiosyncrasies—is on full display, but this book is much more than just a collection of cartoons. At time where graphic novels and memoirs are finally receiving the acclaim they deserve, Chast sharply demonstrates the potency of expression that the format allows.

Humor and pathos intermingle freely—and in just the right proportions—but Chast is never mawkish or overly sentimental. She is honest and understandably distraught, and she is not afraid of airing her own shortcomings.

“Meanwhile, my father lived with us,” she writes after chronicling her mother’s transfer to an assisted living facility. “Any Florence Nightingale–type visions I ever had of myself—an unselfish, patient, sweet, caring child who happily tended to her parents in their old age—were destroyed within an hour or so.”

When it became apparent that both parents required assistance beyond her abilities and had to leave their apartment in “DEEP Brooklyn, the Brooklyn of people who have left behind everything and everyone,” Chast “began the massive, deeply weird, and heartbreaking job of going through my parents’ possessions: almost 50 years’ worth, crammed into four rooms.”

Here, the author briefly shifts formats, delivering pages of actual photos of the accumulation of stuff over those years in their cramped, grimy apartment, including “random arts supplies,” hundreds of pencils, a drawer of jar lids, and decades-old first aid supplies—not to mention whatever is molding in the fridge. It’s the perfect complement to the text-and-cartoon portrait of her parents she paints throughout the narrative, a portrait she echoes later when her mother is near the end, “existing in a state of suspended animation. She was not living and not dying.”

In the last few pages of the book, Chast includes a showcase of her pencil drawings of her mother as she took her last breaths in 2009. These pages sit in stark contrast to the dynamic emotional roller coaster that has unfolded over the previous 200 pages, a fitting, understated closing frame to a story that, though universally relatable, has rarely been as powerfully rendered. For anyone going through a similar situation, skip the end-of-life self-help shelf and pick up this book instead.

More:

Kirkus review of the book, which won the 2014 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction.

New York Times review.

Guardian review.

San Francisco Chronicle review.

NPR interview.

Chast’s appearance at Politics & Prose.