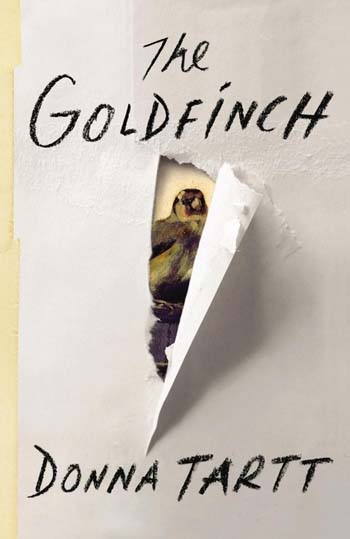

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, in the ninth of our 30 Books 2013 series, NBCC board member Colette Bancroft offers an appreciation of Donna Tartt's fiction finalist, “The Goldfinch” (Little, Brown and Co.).

Donna Tartt’s novels arrive only about once per decade, but “The Goldfinch” is more than worth the wait. Deeply anchored in the traditions of novelistic storytelling yet freshly contemporary in its tone, subject matter and approach to art, “The Goldfinch” is, like its namesake painting, a strikingly original work.

It begins with a bang. One April morning when Theo Decker is 13, he and his mother, a breezy beauty with a lively intelligence, make an impulsive stop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is exhilarated by an exhibition of Dutch Old Masters, including Carel Fabritius’ 1654 painting “The Goldfinch,” but Theo is distracted by a girl about his age who is viewing the paintings with an elderly man. Theo has just walked away from his mom for another glance at the girl when a bomb goes off.

Theo says of his mother on Page 7, “Things would have turned out better if she had lived. As it was, she died when I was a kid; and though everything that’s happened to me since then is thoroughly my own fault, still when I lost her I lost sight of any landmark that might have led me someplace happier, to some more populated or congenial life.”

It’s a fine bit of foreshadowing, except almost everything in it might be wrong. Certainly Theo’s life is richly populated, with a cast of characters Tartt brings to life with skill and heart. There’s James “Hobie” Hobart, the gentle restorer of antiques whose Greenwich Village townhouse becomes a healing haven for Theo. There are the members of the wealthy and quietly weird Barbour family, who take him in. And, when his dreadful estranged father shows up and whisks him off to the barren suburbs of Las Vegas, there is Theo’s friend Boris Pavlikosky, a thief, a liar, a brawler, an enthusiastic drunk and abuser of drugs, a hilarious storyteller, a resourceful ally and one of the most memorable characters in recent fiction.

In terms of style, “The Goldfinch” is several novels in one, each of its five sections distinct. The nightmarish account of the museum explosion and its aftermath, the warm domestic charm of Theo’s early relationships with Hobie and the Barbour family, the black comedy of the Las Vegas episode, the crisp social satire of the chapters about Theo’s engagement, the feverish noir of the book’s last section – each has its own integrity of style and tone, yet each contributes to the larger story.

Although it draws upon many influences, “The Goldfinch” echoes in particular with the works of Charles Dickens and J.D. Salinger. With its vividly drawn characters and its complex, sometimes coincidence-driven plot, “The Goldfinch” recalls such books as “David Copperfield,” “Oliver Twist” and “A Christmas Carol.” Like Salinger, Tartt writes mostly about young people and has an uncanny knack for capturing their voices. As the book's narrator, Theo has a quick intelligence, observant eye and cynicism as shield for a battered heart that recall Holden Caulfield.

But “The Goldfinch” is no copy; it's the real thing. Tartt's style, lush with description and crackling with great dialogue, is her own. And the story she tells, by turns heartbreaking and heartwarming, terrifying and thrilling, is irresistible.

New York Times interview.

Washington Post review.