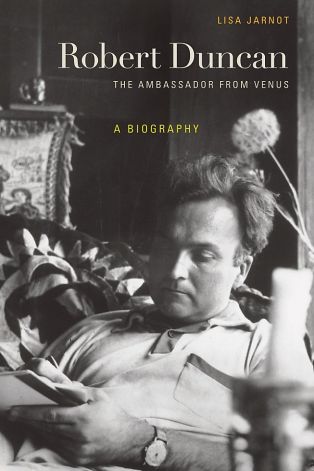

In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member Stephen Burt offers an appreciation of biography finalist Robert Duncan, The Ambassador from Venus: A Biography (University of California Press) by Lisa Jarnot.

If you believe that poets are a special and inspired kind of person, visitors or vessels or inhabitants of energies that the rest of us don’t know, then Robert Duncan (1919-1988) might well be, for you, the major poet of our century: few writers anywhere have lived out so ferociously, so sincerely, so gregariously the ideal of the prophetic poet’s life. If you believe in magic—in the occult, or in American literature inspired by the occult, by hermetic and mystical traditions—then Robert Duncan is surely a poet for you. And if you believe in none of those things, but you take a sustained interest in the poets and poetry of the American West Coast, from the Beats and the Berkeley Renaissance through Thom Gunn and Michael Palmer to the present day, then you may need to read up on the life of Duncan, whose charismatic productions so often connected these poets to one another; many venerated him. Lisa Jarnot’s thorough and responsible biography gives us a chance, at last, to do just that.

If you believe that poets are a special and inspired kind of person, visitors or vessels or inhabitants of energies that the rest of us don’t know, then Robert Duncan (1919-1988) might well be, for you, the major poet of our century: few writers anywhere have lived out so ferociously, so sincerely, so gregariously the ideal of the prophetic poet’s life. If you believe in magic—in the occult, or in American literature inspired by the occult, by hermetic and mystical traditions—then Robert Duncan is surely a poet for you. And if you believe in none of those things, but you take a sustained interest in the poets and poetry of the American West Coast, from the Beats and the Berkeley Renaissance through Thom Gunn and Michael Palmer to the present day, then you may need to read up on the life of Duncan, whose charismatic productions so often connected these poets to one another; many venerated him. Lisa Jarnot’s thorough and responsible biography gives us a chance, at last, to do just that.

The last of his biological mother’s ten children, Duncan was adopted as an infant by an Oakland family given to spiritualism: his parents may have believed that he was a messenger from Atlantis, though after their move to Bakersfield in 1927 the Duncans led a conventional bourgeois life. Robert’s teenage escapes included poetry, the movies, and sexual trysts with other young men. Attending the University of California at Berkeley, he accreted the first of his many circles of collaborators and admirers, among them the painter Virginia Admiral, and he began his own never-ending, idiosyncratic, and decidedly ambitious program of study, promoting—before it was fashionable—H.D. and Gertrude Stein as modernist models. (Duncan would labor for decades on the study he called The H.D. Book, published posthumously in 2011.) In 1939 he followed his first great love, the graduate student Ned Fahs, out of Berkeley and to the East Coast, where Duncan would start little magazines, labor on unfinished books (one called The Shaman as Priest and Prophet), and make his first contact with Black Mountain College, the experimental school in North Carolina, active until the mid-1950s, whose radical, sometimes spontaneous, often collaborative artistic practice would inform Duncan’s own. (The last event ever put on at Black Mountain was a performance of one of Duncan’s plays.)

Duncan’s New York City years also began his astonishing web of connections, not just with other poets, but with eminence in the other arts. Jarnot shows how he knew and often inspired, in New York and North Carolina and in the Bay Area, the future film critic Pauline Kael, the fiction writer and memoirist Anais Nin, the filmmakers Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage, the philosopher Norman O. Brown, the painter R. B. Kitaj, the social critic and activist bell hooks, as well as the poets of four generations on three continents—H.D., Spicer, Ginsberg, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, Kenneth Irby, the Scottish concrete poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, the Scottish Bay Area poet Helen Adam, Jerome Rothenberg, Gunn, Palmer, Bernadette Mayer, Aaron Shurin, Australia’s Robert Adamson.

Briefly in the army, briefly married, Duncan returned to San Francisco in 1945 ready to take part in the Berkeley Renaissance, along with Robin Blaser and Jack Spicer, who shared his homosexuality and his mystical convictions, but not his outgoing personality. Olson called Duncan an ambassador from Venus; Spicer liked to say that his poems came to him over a radio from Mars. Yet the poets made their discoveries together: “through conversation and correspondence with Spicer,” writes Jarnot, “Duncan was pushed. to study the linguistic basis of poetry, arrange objects in poems as magical talismans, and question the role of poetry and language in the world.” The results were long-lined free verse poems that could sound incantatory, or exploratory, or hesitant: their breaths and pauses seemed to reflect not so much any older traditions of artful writing as a practice of considered, spiritualized speech, “a record of what we are,” as Duncan told Levertov, “like the record of what the earth is left in the rocks.” (Duncan resolved in 1958 not to revise; thereafter, his published poems were his first complete drafts.) Jarnot quotes one of Duncan’s early poems that could have been a manifesto (the idiosyncratic spellings were a lifelong practice):

The shaman sends himself

the universe is filld wth eyes then, intensities,

with intent,

outflowings of good or evil

benemaledictions of the dead,but

the witness brings self up before the Law.

In 1952 Duncan and the painter Jess Collins (known simply as Jess) moved in together; they would remain a couple for 36 years, Duncan’s high-energy talk and wish to travel increasingly set against the introverted Jess’s desire to stay home. Duncan and Jess were nonetheless a model for a long-term, happy, openly romantic, same-sex couple when such models were thin on the ground, and their works (collages, paintings, essays, poems) kept paying homage to one another in subtle as well as overt ways. Duncan’s life in the Bay Area during the 1950s and 1960s was at once domestic and busily public; he helped run the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University during the years when the Beat scene took off, and though he quit that job after a few years he never thereafter lacked for poetic companions, students, admirers. Close friends and hosts in his travels remembered him as someone who could hold their attention, but also as someone who would talk nonstop: his dramatic garb, which could include robes and a Spanish-style cape, served as prologue to his linguistic endurance feats.

And he would travel: to New York, to Black Mountain, and, as the decades went on, to Buffalo, to Canton, to Hudson, N.Y., to Vancouver, to London, to Boulder, to Chicago, to Paris, to Innsbruck, Austria, to Ketichan, Alaska, to Sydney, Australia, a beneficiary of the poetry reading circuit that took in more and more festivals and universities in the last half of Duncan’s life. Jarnot’s thorough, responsible book begins as a Kunstlerroman, a book about the making of a very serious artist. Its final third has the feel, instead, of a travelogue, as Duncan visits, inspires, and talks with—or talks at, or out-talks—the poets and teachers in one city after another, especially during the fifteen years between Bending the Bow (1968) and Ground Work I: Before the War (1982), in which he remained on the circuit, delivering lectures and giving readings, while refusing to publish a book of new poems.

And yet the real action remained on the West Coast: there he returned to write, there he kept up his household with Jess, there he took part in, then distanced himself from, protests against the Vietnam War. A declared anarchist, Duncan opposed the war, but he also opposed direct efforts to make poems take part in headline news, in politics, an opposition that led him to his famous break with Levertov. Jarnot documents the Vancouver Poetry Conference of 1963, the Berkeley Poetry Conference of 1965 (Spicer’s last public appearance), the shamanic lectures at Santa Cruz and elsewhere, and the confrontation at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1978, where Duncan interrupted the young avant-garde poet-critic Barrett Watten and attempted to drive him offstage. Watten and his peers, the Language writers, would define their skeptical, anti-mythological, intellectual methods against the intuition and charisma that Duncan could represent, even as they inhabited the Bay Area poetry communities that Duncan and his generation helped to build.

Known for her own compact and serious poetry—some of it song-like, some of it like magic spells—Jarnot has been at work on Duncan’s biography for 25 years; the result might disappoint any reader expecting something overtly “experimental,” but it’s what scholars and fans need: a traditional soup-to-nuts, birth-to-death biography, a serious, meticulous, detailed, and extraordinarily documented record of what Duncan did and said and wrote, and where, and when, and with whom, with reference to Duncan’s own verse, and his letters and notebooks, in which he sometimes (but only sometimes) told us why. That verse and its justifications are not to everyone’s taste, and will never be, but its influence—and the influence of Duncan’s unrepeatable life—remains undeniable: poets as unlike him as Elizabeth Bishop (who knew him in the late 1960s in San Francisco) admired the man, and Jarnot shows why, with facts, dates and careful quotations, not least this introduction he wrote for himself in 1963: “What I call the Divine is what I begin to divine in the poem… The dream, the dance, the falling-in-love and the poem seem to me of one kind.”

Links:

Ange Mlinko’s review in The Nation

UC San Diego professor Seth Lerer’s review in the San Francisco Chronicle

Foreword to Jarnot’s book, by poet and UCSC professor Michael Davidson