When we asked NBCC members to talk about their favorite books about music, nobody gravitated to one particular genre. Indeed, many respondents selected multiple books that addressed a variety of styles; more on those soon. But a few picks were firmly rooted in rock/punk/blues firmament, starting with Larry Baker's pick, Life in Double Time, a 1997 memoir by drummer Mike Lankford. Baker writes:

When we asked NBCC members to talk about their favorite books about music, nobody gravitated to one particular genre. Indeed, many respondents selected multiple books that addressed a variety of styles; more on those soon. But a few picks were firmly rooted in rock/punk/blues firmament, starting with Larry Baker's pick, Life in Double Time, a 1997 memoir by drummer Mike Lankford. Baker writes:

Lankford's memoir is the best book ever written about life on the road as a musician. Not the glamorous life of the superstars, but the daily grind of living out of a van and dodging beer cans in a redneck honky-tonk. His story begins like all musicians' stories begin: practice practice practice in somebody's garage and then high school band contests, all in preparation for the big time with groupies and stardom. But Lankford takes us on the road traveled by most musicians: long drives, cold nights, minimum wage pay. His description of the time he spent as the white drummer in a black trio is rendered in prose that is both meta-physically insightful and descriptively physical. Lankford's journey is laced with violence and drugs and sex, but his language is brilliantly funny as well as graphically disturbing.

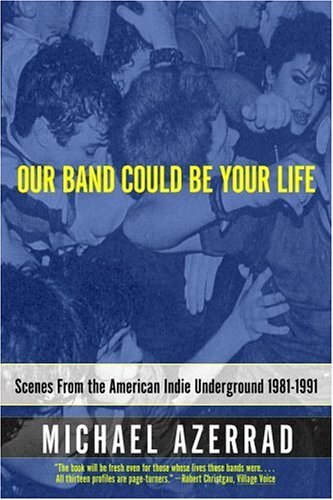

David Varno chose Michael Azerrad's expansive history of American postpunk, Our Band Could Be Your Life:

This may be a predictable choice for someone of my generation (who first heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit” while in the fifth grade), as Please Kill Me would be for another, but its appeal is made up of more than great stories. Azzerad succeeds in articulating a loose, hard-to-define network of voices that screamed before and well past the hype of Nevermind. While Legs McNeil catalogued the destructive thrill of punk, its unconsciously heroic nihilism, Azerrad went after the D.I.Y. spirit that congealed in the ashes, a set of codes that, if not for the practitioners' continued rebellion, would have been more at home in a suburban Boy Scout troop than on the Bowery, the streets of Detroit, or Sunset Boulevard. As Azzerad wrote in his introduction, “The Minutemen called [D.I.Y.] 'jamming econo.' And not only could you jam econo with your rock group—you could jam econo on your job, in your buying habits, in your whole way of life…You could take charge of your own existence…as the Minutemen put it in a song, 'Our band could be your life.'”

And Paul Wilner weighed in with a handful of recommendations:

Start with Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta, by the late, great Robert Palmer (the musician and critic, not the British musician, although Palmer also played clarinet for the the seminal band the Insect Trust, so-named for a passage in Naked Lunch). Palmer was extraordinarily knowledgeable without ever falling into archival reverence. The contributions of Robert Johnson, Sonny Boy WIlliamson, Muddy Waters, and lesser-known but no less worthy lights like Junior Kimbrough are all recorded here with a passion no less effective for being minimal, Palmer passed too young, at 52, beset by his own demons, but his work continues to command, and demand, attention.

Also on the Southern spectrum, no one–and I mean no one—has written about the Rolling Stones better and with more passion than Georgia's Stanley Booth in The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, his harrowing account pf the band's infamous 1969 tour, culminating in the Altamont debacle. “He was terrified,'' Booth writes of Mick Jagger at the outdoor “celebration.'' “And so, it must be said, was I.''

One more addition to the rock lore: Mikal Gilmore's Night Beat: A Shadow History of Rock and Roll.' A winner of the NBCC nonfiction award for Shot in the Heart, his 1995 memoir of his troubled relationship with his brother Gary, Gilmore always brings a searing social consciusness and a deep respect for his subjects—even when they deeply annoy him, like Keith Jarrett, to his work. Whether he's writing about Dylan (whom he recently interviewed for a cover story for Rolling Stone) or Michael Jackson, Gilmore always finds a way to bring it back home.