Many of the works of literary journalism recommended in the latest iteration of NBCC Reads fit into neat categories: war stories, travel pieces, immersion journalism, and so on. Many don't, though. Which doesn't make them any less worthy, of course. If anything, they reflect the diversity of the form. Donna Iverson, for instance, recommended Masha Gessen's blend of history and biography, The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. Wendy Lesser, editor of the Threepenny Review, recommended an eclectic early work by one of the New Yorker's finest reporters:

Many of the works of literary journalism recommended in the latest iteration of NBCC Reads fit into neat categories: war stories, travel pieces, immersion journalism, and so on. Many don't, though. Which doesn't make them any less worthy, of course. If anything, they reflect the diversity of the form. Donna Iverson, for instance, recommended Masha Gessen's blend of history and biography, The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. Wendy Lesser, editor of the Threepenny Review, recommended an eclectic early work by one of the New Yorker's finest reporters:

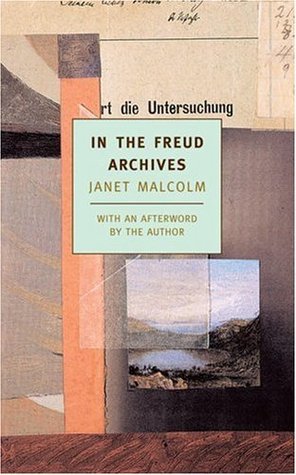

My favorite work of literary journalism is Janet Malcolm's In the Freud Archives. I have read this book several times and always find it different and exciting in new ways, just as one does with a novel. The narrative voice is brilliant, the people in it masterfully portrayed. I am an admirer of all of Malcolm's work, but this one, I think, is my favorite.

Steve Wasserman chose two books, published three decades apart, that shed light on two different aspects of California history and culture:

Carey McWilliams’s Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California. Published in 1939 just two months after John Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath, McWilliams’s muckracking expose of the depredations inflicted on workers and upon California’s Imperial Valley by the growth of corporate agriculture was, like Steinbeck’s fictional portrayal, a national best-seller. It was, in the words of The New York Times, a story “masterfully told.” It sadly remains as relevant today as it was nearly three-quarters of a century ago.

Robert E. Conot’s Rivers of Blood, Years of Darkness. It is a remarkable anatomy and investigative reconstruction of the 1965 Watts riot, the first of the racial disorders of the 1960s. Published in 1967, Conot was indefatigable in his efforts to put a human face on a conflict that was, for many Americans, as surprising as it was violent. Interviewing more than 1,000 people and taking written statements from another 500, Conot succeeded in writing a moving and incisive post-mortem of an uprising whose most difficult lessons, alas, still elude us.

Jane Ciabattari recommended a more recent work of longform reportage:

“After the Tsunami: Nothing to Do but Start Again,” by Charles Graeber, published in Bloomberg Businessweek, winner of this year's Overseas Press Club Ed Cunningham Award for magazine reporting for abroad.

Graeber reported on the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami in Kamaishi, Japan, focusing on the story of one family — 80-year-old Kenji Sano, and his son, Shigeru, who ran a liquor business and bar. He tells the tale with texture, fresh language, empathy, and dimension. Graeber gives a multi-generational perspective to a town that has been battered by nature and decimated by bombings and nuclear holocaust without dirge-like drumbeats. A man survives and continues. A smashing piece of work.

I chaired this year's OPC Ed Cunningham awards judging committee, with fellow judges John Freeman, former NBCC president and editor of Granta, and Joel Whitney, OPC board member and editor of Guernica.

And Michael Lindgren admires the sole work of sportswriting that was recommended in our informal poll:

Most sportswriting barely qualifies as journalism, let alone literature, but to my mind the finest exception in both categories is the writing on baseball that Roger Angell did at the New Yorker in his heyday, from 1963 to 1987 or thereabouts. For a quarter century Angell wrote about baseball with peerless grace, precision, and intelligence, a corpus that was collected and issued every five years in handsome Houghton-Mifflin hardcovers, battered, plastic-slipcased copies of which found their way into my hands courtesy of the Boston Public Library. Roger Angell educated me not just in how to be a baseball fan, but how to be a writer. To this day I hear in my mind's ear, when struggling to shape sentences, echoes of the rhythms of his prose, lucid, lightly erudite, casually poetic, and warmhearted.

To wrap up NBCC Reads in the coming days, we'll include a couple of contrarian views on the form, and a last word on literary journalism from the person who's arguably most closely connected to the term.