The latest NBCC Reads question asks: What is your favorite work of literary journalism? Here, member Richard Melo considers the legacy of Tom Wolfe:

Tom Wolfe? Ewwwwwww. Him? Get outta town. Tom Freakin’ Wolfe. He sure ain’t no Thomas Wolfe, or Tobias Wolff, or Virginia Woolf, or Howlin Wolf. He’s the least of all writerly Wolves, while jes mebbe the most wolflike of ‘em all.

Tom Wolfe? Ewwwwwww. Him? Get outta town. Tom Freakin’ Wolfe. He sure ain’t no Thomas Wolfe, or Tobias Wolff, or Virginia Woolf, or Howlin Wolf. He’s the least of all writerly Wolves, while jes mebbe the most wolflike of ‘em all.

Okay, I’ll stop writing like that now. While that isn’t exactly the reaction I get when I mention that I like Tom Wolfe in the company of book people, I have found that mentioning the man in the white suit often rubs people the wrong way.

What does the world hold against Tom Wolfe? It could be his conservatism, including his defense of the values of George W. Bush, or that the famously non-reading ex-president counts himself a Tom Wolfe fan.

It could be the sound effects Wolfe writes into his prose (like repeating the word hernia over and over to mimic the sound of a Las Vegas slot machine), a technique many writers give up after the eighth grade. Did I mention the white suits?

Wolfe isn’t beloved in the same way as other literary journalists of his time: Hunter Thompson, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, to name three. Those writers work hard to bring you over to their side. Wolfe is more comfortable as the outsider’s outsider. If one of the premises of American literary journalism is to hold up a mirror so people can see how they appear to others, the mirror image that Wolfe wants readers to see is that of a pig. Scathing satire won’t win you many friends when your readers are among those you’re mocking.

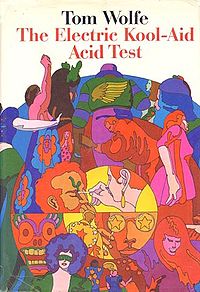

Long before the Mike Daisey era, Wolfe stirred a truth vs. fiction pot of his own. Wolfe’s brand of the New Journalism included getting inside the heads of the people he wrote about, second guessing thoughts and intentions, and calling it reporting. One example is his description of the psychedelic and paranoid freakout of a Merry Prankster named Sandy in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Readers said there was no way Wolfe could be that much inside Sandy’s head, that he was using too much of a fiction writer’s license in his writing. Unlike Daisey, Wolfe knew what he was doing. He was giving readers something to talk about, and talk about it, they did, and he sold a lot of books.

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, is the seminal book depicting the 60s youth counterculture written in real time; it took years for novel writers to catch up. As a bright blue paperback that put the mass into mass market, it was a book that hippies heading out to communes took with them, and a book that affirmed the Silent Generation’s worst suspicions about young people. You can look at The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as the middle book in a trilogy that begins with On the Road and ends with Helter Skelter.

No stranger to controversy, Wolfe in the late 1990s embroiled himself in a real, live literary feud. It began with Wolfe’s supposition that novelists ought to to draw from the reporter’s bag of tricks and base their fiction on real people and events more than their imaginations. It ended in a bout of public name-calling with Wolfe on one side and strange bedfellows John Updike, Norman Mailer, and John Irving on the other. While Wolfe’s prescription for the novel never came to pass, and if anything has gone in the other direction with the reverie around novels such as The Road, Wolfe’s own The Bonfire of the Vanities is the pinnacle of the late twentieth-century Dickensian journalistic novel and a blueprint for other novelists wanting to see how it’s done.

There’s more to why I like Tom Wolfe. I admire his technique of describing the actions of his subjects/characters with the same speech pattern they would use in describing themselves. I also think highly of The Right Stuff, and how Wolfe took the sprawling history of the space program and managed to base the story around the verbal tics of the key players (phrases like “pushing the envelope” and “screw the pooch”), and the book’s opening chapter is one of the best pieces of journalistic storytelling I’ve ever read.

However, what I find most remarkable about Tom Wolfe is his writing on race. White, male writers often carry on like race is invisible, except when writing about it is either a) convenient or b) unavoidable. Wolfe’s writing starts with the premise that race isn’t just hiding in plain sight, that race is everywhere. Race is certainly front and center in his three novels (The Bonfire of the Vanities, A Man in Full, and I Am Charlotte Simmons).

Underlying Wolfe’s satire is the idea that people getting worked up over skin color is ridiculous, which is not itself an innovative concept. From there, Wolfe pushes the envelope, mocking the excesses not only of the white establishment but also those of anti-racism activists. The most prominent of Wolfe’s pieces in this vein is the 1970 article “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” about a fundraiser Leonard Bernstein threw for the Black Panthers where the players come off more self-serving than altruistic. when Wolfe writes about race, reader reactions often fall somewhere in between a squirm and a cringe, but there is laughter in there, too. Satire likes to hammer home the point that everything is stupid, but with the subtext that it can be better. As a pop figure doing social commentary, Wolfe might have more in common with Dave Chappelle than many of his literary contemporaries.

Over time, Wolfe’s legacy might center more on his race writing than his contributions to the New Journalism and the other hot buttons he pushed.