“Friends, Writers, and Other Countrymen,”Sidney Offit’s new memoir, covers some 60 years of American literary life, from encounters with H.L. Mencken in his native Baltimore, where he also recalls meeting Rose Burgunder [later Styron] at a dance in 1948 when she was the belle of “Bawlamer,” to decades of writing (novels, “Memoir of the Bookie’s Son,” books for young readers), editing (at “Intellectual Digest,” where he worked with Borges, Neruda, and Octavio Paz), teaching (he still teaches at the New School), administering the George Polk journalism awards, and serving on the boards of PEN American Center and the Authors Guild.

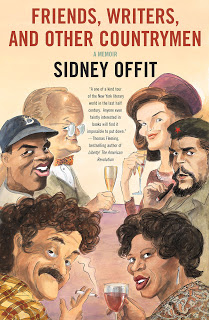

The cover is a masterpiece by Ed Sorel, depicting six of the hundreds of iconic characters within: Jackie Kennedy (“We met at a book party for a book she edited, Francis Mason’s Balanchine book,” Offit recalls), Che Guevara ( “My son Ken says I’m one of the few people who has both smoked a cigar with H.L. Mencken and received a box of cigars from Che Guevara”), Toni Morrison (“we were colleagues on the Authors Guild board; later, at a party honoring her Nobel, she said to me, ‘You should be home writing.’”), Truman Capote (“We met when I dropped by a Southampton book shop to sign copies of my new book, “What Kind of Guy Do You Think I Am,” and Capote asked, “What kind of guy are you?”), Jackie Robinson (“I interviewed him in 1956 at Ebbets field. I asked about the rumor he was being traded. Robinson told me, ‘It doesn’t surprise me; I’ve known all along that all I am here is chattel.’ I thought it was too intimate a conversation to report, and missed my first scoop”), and longtime tennis partner Kurt Vonnegut (“he annointed me his best friend”).

Offit recalls the founding days of the National Book Critics Circle, in 1974 at the Algonquin: “The founding of the NBCC was a response to the overwhelming dominance of the Pulitzers,” he said. In particular, he recalls one of its founders, the New York Times Book Review’s Nona Balakian, for whom the NBCC award for criticism is named. “Nona was a literary enthusiast. Among people I have known, a vast assembly of writers and critics, Nona was the one who took the vows. It was totally her life. Many critics had diverse lives, wrote fiction or nonfiction, had other things in their lives. Nona was almost totally absorbed by her life as a good critic. She was really aware of what was being published. Which isn’t true of everybody who is a critic. Nona tried to be aware of everything.”

And how have things changed? “In the early 1960s, book critics did not socialize with writers very much. They were very cautious. Book critics I knew didn’t think it was a good idea because of the awkwardness when you know a writer and don’t review their book, or review it negatively. All of that changed dramatically in the 1970s. Critics would come to PEN cocktail parties and they become part of the fabric of the organizational life of writers.”

And as an author? “When I published my first book, a novel about the Catskills called “He Had it Made,” I was unaware of criticism. When I had a front page review in the New York Times, I didn’t know how consequential it was. Now I am overly aware because I know so many people in the publishing business. Even at my ripe old age, with the full life I’ve had, when I walk into a book store and look at the magazines I feel vulnerable.

Reviewing isn’t “inflicting momentary pain,” he says. “I don’t know if reviewers knew how unforgiving writers can be. Norman Mailer called attention to his bad reviews by being infuriated. Updike has lots of negative reviews. Even Roth gets clipped. I don’t mean modest reviews. There’s no question that the investment of soul and ego in books is almost universal.

“We have a passion in this country for rating and listing. I don’t think writing is competitive. The enduring work is very difficult to predict. So much of it is determined by the subjective taste of later critics.”

Approaching eighty now, Offit has learned a thing or two about the question of literary immortality. “You write books mostly for yourself,” he says, quotes a line from Shelley’s “Ozymandias”—“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”—and adds, “I love writing about my father, because my father gave me that bookie’s pragmatism.It’s great fun to have had a shot at it. You never know what’s around the corner….”

And off he goes.