This is the first in a series of blog posts by NBCC board members covering the finalists for the NBCC awards. The awards will be announced on March 6, 2008, at the New School.

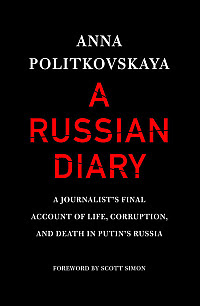

A RUSSIAN DIARY: A Journalist’s Final Account of Life, Corruption, and Death in Putin’s Russia, by Anna Politkovskaya (Random House.

Journalism has always been a potentially deadly game, especially when played by the time-honored creed of comforting the afflicted and afflicting the powerful. This was how the 48-year-old Anna Politkovskaya chose to do her work, and, apparently, it’s why she was one of 13 journalist killed in Russia since Vladimir Putin came to power. Her murder in 2006 remains unsolved.

“A Russian Diary” is a posthumous testimonial to Politkovskaya’s reportorial skills and her despair about what has happening to her country. Drawn from the journals she kept between December 2003 and August 2005, it frames Putin’s reelection as a rigged event that, among other things, pulled the curtain on how the government responded after Chechen terrorists took hostages in a Moscow theater in 2002. Politkovskaya, who went to Chechnya 39 times as a reporter for the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, had been called in to try to negotiate with the hostage takers, but to no avail. Russian forces stormed the theater, killing not only the terrorists but also 130 of the 912 hostages. She held the government accountable.

Politkovskaya boils over with anger in 2004 when the same kind of tragedy takes place in Beslan, a small city near Chechnya. There, Chechen separatists invade a school containing 1,200 innocents—teachers, parents and children. Once again, negotiations fail, and 331 die. Politkovskaya describes the bewildered survivors, including one mother who was horribly injured and still waits for her son to come home. Even though the military collected remains of boys her son’s age, they’ve never been identified. “Zhorik in a bag? Never!” the mother cries.

Politkovskaya’s journals show us a Russian state that’s under siege much as the school was, with Chechens and Muslim radicals serving as both a reason and an excuse for curtailing freedoms. An unpopular distant war requires scouring for soldiers and fending off the Party of Soldiers’ Mothers, with the “maternal urge that sweeps all before it.” Politkovskaya, a mother herself, sees this new party as one of the few real antidotes to Putin’s “diabolical cynicism.”

For journalists in this new Russia, she says, the “choice is not between having a job or being unemployed, but between earning a fortune or a pittance.” Collaborators are paid well, she says, just as the oligarchs who cooperate with the government are colleting fortunes while pensioners starve.

As Scott Simon points out in the book’s introduction, Politskovskaya knew she was in danger and could have left Russia to spare herself. She could have retired to be with her daughters and her new grandchild. Instead, she chose to earn a pittance—and to write the truth as she saw it. “A Russian Diary” is a worthy tribute to her relentless zeal for reform and justice.