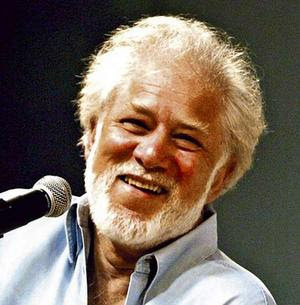

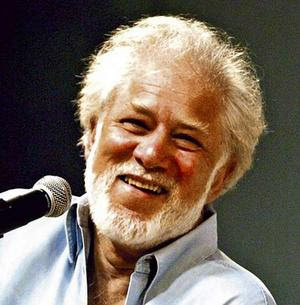

The following essay comes to us from Molly McQuade, former NBCC board member, poet, and author of the critical volumes “By Herself” and “Stealing Glimpses.” Here, in this first part of a three-part essay, she steals glimpses of critics as they grapple with Michael Ondaatje’s latest novel, “Divisadero.”

A TOP LITERARY editor who lost his job in book publishing not long ago said to me in passing, more recently: “The book review as it used to be is never coming back.” (Since he is sixty-something, he spoke with a certain wizened, knowing rue.) The editor went on to cite the New York Times Book Review as a good example, he said, of the undeniable, necessary limits of the current state of the art. Then he mused, “And just think of what even they are up against . . . .” Then, he said again what he had said only an instant before: “The book review is never coming back.” Finally, he changed the subject, never to return.

Even if the book review as it used to be is never coming back, back it comes to my mind now anyhow, only partly because my friend the editor said that it “never” could. Despite the widely mourned decline, over the past twelve months, in numbers of reviews published in mass-circulation venues, some reviews indeed remain among us. The next review, like the last, may quite possibly be published, and—improbable as this may sound—it may quite possibly be read. For those reasons, after a year of unusual tumult in the book-reviewing business, would it seem timely to review a few of the reviewers who continue, against whatever odds, to read and write?

The idea is half bad, and half good. Bad because it encourages intramural nitpicking when what the profession most needs, arguably, is money, vigor, and unforeseen imagination. Bad too because the idea itself doesn’t sound particularly joyful, or even—perhaps—all that illuminating. Yet it’s good, also, because if publishers (and advertisers) belittle the need for criticism, then who but a critic should try to prove them wrong, right, irrelevant, lazy, or crazy? Besides, although I don’t yet talk to myself (later, it may happen), I do think to myself, like many a critic, much of the time; and, just like any other critic, I pine to “share.” Lastly, I’ll pursue my idea because some questions seem worth asking at a moment when outsiders to the work of book reviewing have dashed the enterprise, or tried.

A few of my questions: what have we done, this past year; how did we do it; and why care?

To narrow the field to a tolerable squinting range of possible answers, it seems fair to choose a single new book that, when first released, seemed likely to pose an interesting challenge to critics and to evoke varied reactions in a wide span of periodicals—and then, to survey those. The book I’ve chosen is Divisadero by Michael Ondaatje, a novel published by Knopf last May. Unlike some other difficult and enticing books of 2007, this one would not be ignored. Enough time has passed by now for us to be able to look backward at it, but not so much that we’ll forget how.

For the most part, I’ll limit my survey to reviews not written for the chosen few. Or, even if they were written for the few, they were published for the many, in large-circulation American newspapers and periodicals. My logic: if that’s where book reviews have lately fallen on the hardest times, because publishers assume that most Americans will rarely read any, then that’s a prime place to check now for critical vitality. Either it’ll be there, or it won’t.

A disclaimer: Michael Ondaatje is a writer whose books I would much rather read than review, although I can’t say how other critics feel. Did most seek out their Divisadero assignments, or merely receive them from above, unasked for? In fact, I have never reviewed him, though I have often taught his work to undergraduates and graduate students, most recently this autumn. While I always savor the moment of entranced bemusement overtaking a typical new reader of his words, to explain the words themselves (or the bemusement) might seem peculiarly at odds with the consciously elusive sensibility of his writing. Better to write in his footsteps, perhaps, than to summarize, adjudicate, or analyze?

Even so, I can’t quite justify my own hunch against reviewing him. Nor would I urge it on the good or bad critics of Ondaatje. Actually, if pressed, I know exactly which three pages in which book of his I might leap to analyze at length, one day. (They are pages 72 through 75, entitled “Tongue,” in his memoir, Running in the Family.) Maybe, some day, I even will.

Until then, another disclaimer: I have read as many reviews, at random, of Divisadero as seemed reasonable. (I have also read, and reread, Divisadero.) I don’t know personally the authors of those reviews, although I might be able to pick out one or two from a lineup. None of them has given me book review assignments, reviewed any of my own books, or edited me. None has served on the board of directors of the NBCC with me when I served. A frequent complaint about book reviewing insists that conflicts of interest beset the work. In this case, none should.

Finally, I’ve never met Michael Ondaatje, and I sincerely doubt that I ever will.

The Incurious

First, a few general remarks on the reviews and reviewers of Ondaatje’s Divisadero.

Incuriosity seems to bedevil us, as critics. (In this, we seem a separate species from novelists.) By incuriosity I mean a range of besetting inabilities, or perverse choices.

For one, as critics, we rarely have ideas that are not already a little old, maybe too old to be called ideas. Old ideas are so familiar, to the writer or the reader, that they can hardly behave like ideas anymore.

But if we do have an idea that isn’t old—and if we decide to share it—usually it comes to no more than a jotted sentence or two. What we don’t do is exactly what should be done with an idea: explore, expand, expatiate, imagine.

Even if we do have an idea, and try to share it, often enough our words can’t keep up with our thoughts. The thought surpasses the nouns, verbs, and adjectives. But if the words fail us, then how can our readers ever find the thought? Those words of ours are imprecise, clichéd, summary, haphazard, or hurried, so that a reader’s mind, like the eye, will begin to wander.

Incuriosity is hard to define or describe by a mind that has grown incurious. Still, asking questions—and pursuing answers, without many expectations—seems a sign of life, for the curious.

Rapture, and Rebuke

Incurious critics may seem the wrong choice, as reviewers of various and sundry books. However, they seem especially unsuited to writing reviews of books by Michael Ondaatje. For Ondaatje does not write books that belong unambiguously to genres—be those fiction or nonfiction, memoir, essay, history, or poetry. Instead, characteristically, he takes what he needs from a genre and makes up the rest, altering or omitting stock ingredients as he wishes. (In a review posted at Amazon.com, A. Lakusta commented that Divisadero “reads more like a collection of three novellas than it does a novel. It also travels in reverse chronological order.” Added Lakusta, “Ondaatje tells you a story, but not all of it. He leaves the unwritten to the reader to piece together.”)

Characteristically, Ondaatje’s way of handling even such a common element as the character in fiction can undermine or replenish a reader’s expectations, as may Ondaatje’s characteristically flexible pursuit of plot. (Some claim that his fiction forgoes plot.) His work has been described by the writer, or by his readers, as formally “Cubist,” “nonlinear,” “collaged,” and “blurred”—none of which says much, in and of itself. But by dint of their maverick structure, his books slink their own fastidious way. His writing seems less likely to explain anything—including itself—than many another writer’s prose. The lack of explanation might tempt curiosity, invite curiosity, or beckon to the curious to “explain” it. In any case, opportunity lurks. And yet, most critics of his most recent book appear to stop short, limiting themselves by their own choice; namely, they either commit rapture or rebuke in their reviews. Although either rebuke or rapture can give me something interesting to read, by itself neither will lead me far enough. The reason is simple: either reaction excludes at least as much as it includes.

stay tuned for part two of this essay…..