The development and rise of the American short story in the 19th century was the result of simple market forces. Because urban populations in America were so unstable, workers moving from city to city as new lands and employment opportunities arose, newspapers found that serializing novels was bad business: advertisement space was worthless alongside a chapter from a novel that no one lived in town long enough to read. British novelists like Dickens and Trollope published their novels first in serial form, and then collected the chapters together to sell as a book. American novelists had very few venues for serialization, which is why the shape of the American literary novel differs so radically from its British counterpart: chapters from serialized novels read like episodes of soap operas—each chapter opens with a crisis that is soon resolved and closes with the introduction of a new crisis or cliffhanger which will be resolved at the beginning of the next installment. Not so with the American novel—think Moby Dick or Huckleberry Finn.

The development and rise of the American short story in the 19th century was the result of simple market forces. Because urban populations in America were so unstable, workers moving from city to city as new lands and employment opportunities arose, newspapers found that serializing novels was bad business: advertisement space was worthless alongside a chapter from a novel that no one lived in town long enough to read. British novelists like Dickens and Trollope published their novels first in serial form, and then collected the chapters together to sell as a book. American novelists had very few venues for serialization, which is why the shape of the American literary novel differs so radically from its British counterpart: chapters from serialized novels read like episodes of soap operas—each chapter opens with a crisis that is soon resolved and closes with the introduction of a new crisis or cliffhanger which will be resolved at the beginning of the next installment. Not so with the American novel—think Moby Dick or Huckleberry Finn.

With no periodical market for the novel in the U.S., writers of fiction in the first half of the 19th century borrowed the form of the short tale from German authors such as Wilhelm Kleist and E.T.A. Hoffmann and altered the form to suit American newspapers. The result was the literary form we now know as the short story.

What we now know as a literary form, however, was originally no more high Art than is pop music today. Short stories were commercial products written for newspapers and magazines by writers who were trying to make a living at it. Poe tried to elevate the short story to the condition of Art, and Hawthorne produced a few volumes; there’s Melville’s Piazza Tales, and the little busybody Washington Irving wrote The Knickerbocker Tales. For the most part, however, the short story was a mere short entertainment akin to a sit-com or hour-long drama on the television.

By the time William Dean Howells took over the editorship of The Atlantic Monthly in 1871 the short story form had split into two distinct categories, the same way other art forms split into that which aspires to the Condition of Art and that which exists only to make money. The literary short story had become an art form, but it was also an art form which paid real money. For instance, Jack London once had a contract with Cosmopolitan to write a story a month for a year at the rate of $1000 per story. I once did the math on this number, using rents in Oakland, California as the index of the value of the dollar, and that thousand dollars a hundred years ago is worth about $250,000 in today’s money, what one would get for selling film rights to Hollywood. When a novelist at the turn of the 20th century needed cash to support the novel-in-progress, he would write a short story, and the money would sustain him nicely for a good long while. And it’s no surprise that the short stories, written for money as they most often were, were generally not of the same caliber or difficulty as the novels produced by the same authors. Compare the difficulty level differences between the stories and novels of Henry James and William Faulkner and this becomes obvious.

The rise of film, however, changed the status and ultimately the function of the short story permanently. Just as photography negated the mimetic function of the art of painting, rendering the imitative function of painting obsolete, film’s rise obliterated the short story’s function of delivering short narratives. This took some time, as not everyone had a movie theater nearby and open all hours of the day and night, but today, with movies available with the click of a mouse or remote control, obtaining a short narrative that not only tells a story but which shows the story as well, the short story, for the greater public, has become an artifact of the past and curiosity of the present.

When photography disrupted the mimetic function of painting, artists responded by making paintings that were decidedly non-mimetic, that used as a premise the notion that what they were painting was not reality, but an artist’s impression of reality. Monet’s Cathedral of Notre Dame paintings are not attempts to realistically render the church any more than Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” is an attempt at astronomical accuracy.

The short story has followed suit. When its narrative function was usurped by film, short story writers focused increasingly on the other aspects of the art of fiction. Robert Coover attempts to obliterate narrative certitude, Donald Barthelme operates like a collagist and pop-culture analyst, John Barth fuses criticism and narrative, the minimalists favor style over substance, and it’s almost a universal law that whatever conflict is introduced is not going to be resolved (in rebellion to film, which almost always resolves conflicts neatly and with divine finality). The short story has responded to film by attempting to render in fiction that which is unfilmable.

The short story has evolved into a different creature than its forbears. The short story is no longer a popular narrative medium. Like poetry, the short story has honed itself out of the public eye and entered the depopulate badlands of Art.

There are very few commercial venues in the country for the short story—Harper’s, The Atlantic, Playboy, The New Yorker, Esquire and perhaps a few others. Short story writers publish in literary journals for nominal pay—a few hundred dollars at best—or, as is usually the case, no pay. The majority of readers of short stories are the short story writers themselves—mirroring the state of contemporary poetry. Operating beneath the radar of any culture but their own, short story writers are creating works of Art that bear little semblance to the works being created by novelists. Uncompensated (except perhaps with university posts), unread, short story writers, like poets, are free to write whatever they want to write without fear of low sales, public censure, or even bad book reviews, since their collections, published primarily on university and small presses, usually don’t get reviewed in anything other than the journals in which the stories originally appeared. The books become curiosities for the literary historians of the future even before they exist in print.

My point, finally, is this: the American Short Story has its own unique history and pattern of development. This history and development is not the same as that of the American Novel, which is still a thriving medium and a medium with a wide range of aesthetic intent. The American Short Story, as a popular form, is extinct. Its descendent, the Short Story as Art Form, survives, albeit in the literary fringes of the culture.

In America the novel is generally (although not overtly) favored, granted more prestige, than the short story.

The American Short Story may be fiction, but it is not the same type of fiction as the American Novel.

Though the Short Story garners less prestige, it is nonetheless as worthy an art form as the Novel.

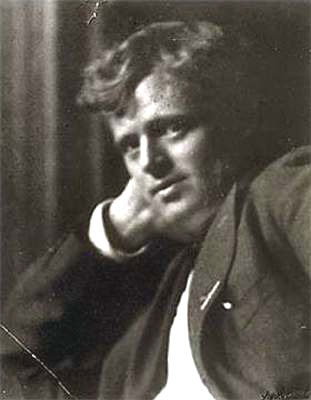

–NBCC board member Eric Miles Williamson is the author of the novels “East Bay Grease,” a PEN/Hemingway Finalist, and “Two-Up.” His new book, “Oakland, Jack London and Me,” is forthcoming.