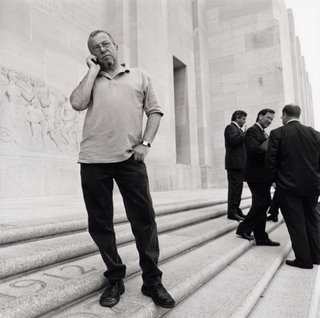

This is the third in our series about New Orleans writers. It's hard to judge how many writers have been displaced, dislocated and disoriented by Katrina and aftermath. Romanian-born New Orleanian Andrei Codrescu is a poet (It Was Today), novelist (The Blood Countess, Wakefield), essayist, screenwriter, English professor (at LSU in Baton Route) and editor of “Exquisite Corpse.” You can hear his NPR commentaries regularly (his Katrina anniversary contribution is scheduled to air on August 27).He answered a few questions on the status of his Katrina recovery.

This is the third in our series about New Orleans writers. It's hard to judge how many writers have been displaced, dislocated and disoriented by Katrina and aftermath. Romanian-born New Orleanian Andrei Codrescu is a poet (It Was Today), novelist (The Blood Countess, Wakefield), essayist, screenwriter, English professor (at LSU in Baton Route) and editor of “Exquisite Corpse.” You can hear his NPR commentaries regularly (his Katrina anniversary contribution is scheduled to air on August 27).He answered a few questions on the status of his Katrina recovery.

Q. Where do you work now? As compared to where you worked before Katrina? (What do you see from your window, for instance?)

A. I'm in my small apartment in the French Quarter in a building only

slightly battered by the Storm. Until last week I heard four Mexican

workers going about fixing the stairs, walls, and gutter. They

listened to a pop station in Spanish and said hello every time I went

out. On the other side of the building, another crew was working on a

crumbling brick chimney. They listened to hip-hop. Right now they are

all gone and the Quarter is empty on a weekday. There are no tourists,

there is no calliope on the river, there aren't even any bums in

Jackson Square. I haven't heard the cathedral bells and I have the

feeling that the city is dead. Last night I went to see a movie shoot

at One Eyed Jacks, and the hipsters, such as are left, looked tired as

they went through their fifth take of dancing. I'm getting ready to go

to Envie, my internet cafe on Decatur: there are always a few

desperate souls there pouring their souls into their laptops.

Q. Have you been able to pursue any of the writing subjects you were working on

pre-Katrina? Or has the experience fully shifted your focus?

A. Katrina and the Aftermath (my new band) changed everything. I haven't

touched my notes for the Tristan Tzara novel and I haven't looked at

the poems I was supposed to collect for a book. I did write The Storm

Songs, a series of poem/songs that will be released as a CD by the New

Orleans Klezmer All-Stars. It's been an intensely feverish and

creative time, all of it having to do with Miss K, the world-stopper.

I've always thought that the world was ending, but I feel a new

urgency. My artist friends feel the same: the waters started a fire

under our butts. At the same time, it's hard to work if you're

depressed. Exaltation and depression follow each other every few

hours. I feel a bit like a ghost.

Q. How would you describe the difference in your mood between putting together

your earlier collection, The Muse Is Always Half Dressed in New Orleans and New

Orleans, Mon Amour, which includes your powerful rage-filled post-Katrina

essays as well as earlier ones.

A. When I put together that book I was full of rage at our federal,

state, and local governments for permitting this tragedy. I felt that

I was drawing the portrait of a city that would no longer exist. I was

right, but now the moods are shifting as we pass through the Gray

Zone. Here is my latest essay, it's about as current as I can make it:

HOW WE SEE US ONE YEAR AFTER

By Andrei Codrescu

About six months ago I went to St. Bernard Parish with my cameraman

Jason to get my own share of disaster photography for the documentary

that I'm making, which is different from the documentary everybody

else made or is making. Every fifth person in New Orleans is either

making or helping make a documentary. We are like the Amazon tribes

whose families were said to consist of a mother, father, children, and

one anthropologist.

We chose for our first foray a beached shrimp boat in St. Bernard

Parish, that was carried several blocks inland by the storm surge

before it slammed into a house and rested there to provide a backdrop

for the news. On the lawn of the house there was a broken plastic

Santa shadowed by the huge boat, and a bunch of soggy school books. I

bent down to examine a notebook that was having its paged riffled by

the wind, and saw that it was a first-grader's exercise book and the

page I was looking at had on it, written in a child's hand, a poem

entitled “I LOVE SANTA.” I kid you not. It got to me. I read the poem

out loud and a tear I hadn't counted on sprung down my cheek. I hope

that Jason got a closeup.

When I stood up, two women wearing shirts that said, “Make Levees not

War,” were coming toward me, and we struck up a conversation. They

told me that they had houses on that street and that this was the

first time that they'd come back from Dallas after the Storm. I asked

them how badly their houses fared, and they told me that they hadn't

gone to their houses yet, they'd come to see the shrimp boat first

because they'd seen it on the national news. One of them said that she

was afraid to see what remained of the house where she'd raised her

kids, and her friend had tears in her eyes. I was in the middle of

asking another question, when my interview exclaimed: “Now, there is a

real celebrity!” She tore off the lapel mike and headed for Anderson

Cooper, who had appeared suddenly with his own cameraman.

Anderson thought that he might use the shrimp boat as background to

anchor next day's news. I asked him, while he signed autographs for

the residents, how he could keep from becoming part of the story. He

shrugged. Of course, we filmed the whole thing.

Those were the last days of the photogenic disaster when no matter

what you pointed your camera at you were bound to hit pay dirt. On

August 18, just shy of the one-year anniversary, somebody burned down

the shrimp boat. Around the same time, two bulldozers belonging to a

company building a monument to the victims of the Ninth Ward, were

stolen from the site.

The two crimes against image and symbol-making were psychically

related. One year after Katrina, we are no longer photogenic. The

cameras focus on narrow slices of rebuilding, which is all that fits

within the lens. If you've been looking at the city for a year, things

look better. Most of the flooded cars packed in the neutral grounds

and under freeway overpasses are gone. There is no debris in places

most visible to motorists. There are trailers and gutted houses in

every wasted neighborhood. If you look only at the swarms of life in

isolated spots you might feel optimism, but if you look at what's

around these spots you might feel dread instead. Yes, there is a

recovery going on, but there is also a pervasive depression. The media

isn't equipped to deal with both hope and despair, it can only show

and tell one story at a time. The Gray Zone where we live is beyond

its power.

In New Orleans nothing is what seems. People believe things they don't

say and say things they don't believe. To the media, we are

recovering. To ourselves we are sinking. Our heavily mediated and

heavily medicated city is generating paradoxes not certainties. About

the time the shrimp boat burned and the monument-building machines

were ripped off, there was a picture in the newspaper of a young woman

from Los Angeles playing songs on a guitar to St. Bernard residents

waiting in line at a parish office. The singer looked super-optimistic

and the women looked amused and disbelieving, but at least they beat

the August 29 deadline/anniversary for permits to rebuild.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. On my nerves. I'm going to Romania Sept 12 to receive the Ovidius

Prize, their highest literary honor, named after Ovidius, the Roman

poet exiled to Romania by Augustus. Ovid never got to go back to Rome,

but I get to go back to my native first home. Kinky, but I left there

long ago. I may end up being an exile from New Orleans, my second home

now. There just isn't enough time in one life for so many exiles. It

sounds sappy, but you should see Ovidius complaining to the Emperor in

the Tristae: the winters are frigid, the women paint themselves blue,

the locals are cultureless savages.Didn't work for him, I don't think

it will work for the 250,000 New Orleanians in exile who are

complaining right now about the barbaric lack of spices in the foods

of the North and the joyless people of the high plains.

Q. Anything else you'd like to mention? Does anything give you hope about the

future of the city?

A. There are thousands of bright-souled volunteers in the city now

helping gut houses and rebuilding. The hope is them and what they'll

learn here. The city itself will be shaped by developers' money. The

good samaritans will leave their mark in the form of a new spirit of

place that will add itself to the existing genii locus and maybe help

them live. Ask me the same question one year from now.