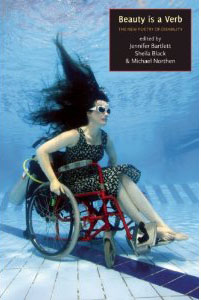

Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability, Cinco Puntos Press, 2011.

Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability, Cinco Puntos Press, 2011.

Edited by Jennifer Bartlett, Sheila Black & Michael Northen

Bartlett’s preface and Northen’s essay “A Short History of American Disability Poetry” situate the need for such an anthology as Beauty is a Verb. Among them, to “look at poetry influenced by an alternate body,” and to highlight writing that “eschewed sentimental poetry that made disability the object of pity or charity” and that “rejected the image of the supercrip, the inspirational hero that overcomes insurmountable odds.” The varied voices in this anthology certainly speak to those expectations and more–they write about (and from) disability with quite a dramatic range of aesthetics and emotions. Indeed, the poems speak for themselves. What roles do you envision for the essays (some biographical and scholarly, others personal) that accompany a number of these poems?

We made the decision early on to compose the anthology of poems and an essay representing each of our contributors in order to crack open a little and allow for the active consideration of what would make a “disability poetics.” Our goal was not to present a monolithic construction of disability—not doing so in fact was very important to us; in part, because all three of us felt that the “traditional” or “historical” stances available to people with disabilities have been so limited. We hope the essays will be used to spread the word that there are many stances available—that disability is a topic that is actively being negotiated and in creative and differing ways all the time by people with disabilities. They also provide for a conversation among the anthology contributors and between an individual poets essay and his/her poems that will be particularly useful in the classroom. As such, the short answer to your question might be, we envision these essays playing multiple roles—but certainly being used in part as tools for teaching.

In Brian Teare’s essay there’s a breathtaking moment when he states, “All along my body has been its own book of wisdom, articulating far more about the terms of living than my mind can always be conscious of.” And another poignant moment (among many!): when Raymond Luczak declares, “I wasn’t going to hide the fact that I was deaf–and gay–in my own writing.” It’s empowering to witness poets refuse to conceal the body from the creative/ intellectual process (a positive affirmation of identity) and to challenge socially constructed stigmas. As you were reading some of these essays and poems for the first time, and watching the community of the anthology grow, what was your initial response? When did it become clear that this project was more than an anthology, but a manifesto of “Disability Poetics”?

As the anthology has grown, it has been very enlightening to all three of us to be in the company of poets/thinkers with all sorts of disabilities who actually have power—or a voice—in society. Our poets are professors, mothers, business people, and lovers with full lives. Like many disabled people, especially women, the two of us with visible disabilities (Bartlett and Black) have often felt very isolated from other disabled people; there tends to be a lot of social pressure on people with disabilities 1) not to claim a disability identity; and 2) not to feel part of any clear-cut group. That is another aspect of working on this anthology that was tremendously rewarding—to realize that while disability culture is enormously diverse, there is an area of shared identity and experience.

We haven’t quite looked at Beauty as manifesto – we wanted to be careful about putting it forth as such because it is not a monolithic, nor a comprehensive vision. Our specific vision for the anthology has to do with negating disability as tragedy and putting forth the idea of social construction. By social construction, we mean that—for example—Bartlett as a woman with cerebral palsy, feels her disability only exists in the way that society negatively reacts to it. Her declaration of resistance to the social and medical model of disability as both a tragedy and something to be fixed is one all three editors share. Yet, to allow difference within disability is very important to us. We are therefore resistant to presenting the book as a manifest—there are so many takes on disability from with the ‘community’ and even the poets within the collection do not agree with each other! For example, while Petra Kuppers is a strong Crip Poetics activist, Josephine Miles would have been suspicious of being in such a collection as Susan Schweik points out in her essay on Miles’ life and work. Jim Ferris and Jillian Weiss are both poets who write unabashedly about their disabilities yet disagree on the trajectory of disability poetics. At the same time, one aim we certainly had in putting together Beauty was refiguring certain poets and poetic stances through a disability lens. We were very taken with Michael Davidson’s idea that, viewed from a certain angle, most twentieth century poetic movements can be understood as types of “disability poetics.”

Readers would not be surprised to find poets such as Kenny Fries, Lucia Perillo and Hal Sirowitz in such an anthology since their particular disabilities are common knowledge. But other poets are “coming out,” for lack of a better term, by contributing their work to an anthology that’s honest and clear about its criteria for inclusion. What sort of conversations did you have as editors about how to approach certain poets who may or may not want to be part of this project or how to reach out to a poet who you didn’t know identified as a person with a disability? A distinction is made between disability and illness or disease, but was there a poet that challenged that particular demarcation? Was the criteria shaped by the editors or by the poets?

One minor correction—Lucia Perillo is mentioned in the anthology, but she is not a contributor. As to how we gained our contributors, the three of us have been working poets—and, in Mike’s case, editor of a poetry journal focused on disability poetics—for some time; we had previous relationships with a great many of the poets we approached. In some cases, these poets were not actively identified as having a disability. For instance, Jennifer wasn’t sure whether Hal Sirowitz or Bernadette Mayer would want to be identified as disabled, but since she knew them both, it was easy to ask. It was a little more difficult with poets we didn’t know, but we worked hard to write a very clear letter of solicitation that outlined the philosophy and goals of the anthology. That really helped. A number of poets we didn’t know came on board due to this statement of purpose. In that statement we outlined our curiosity in exploring disability poetics and addressing such questions as how the experience of disability might influence a poet’s formal choices and/or how disability as a phenomenon might force new ways of looking at “beauty” and “function” in society as a whole. Happily for us, these proved questions a great many poets we were interested in were interested in looking at.

In terms of criteria for inclusion, we decided early on to focus on physical disability and within that context largely visible physical disability because we were interested in how society reacts to a body which appears different. However, there are a couple of poets included in the collection who might ‘pass’ upon first glimpse. Our criteria was also poetic. We are all writers first, and we wanted to choose writing that we found interesting as writing.

As for the distinction between disability and illness, this is an important yet sometimes difficult distinction. None of the poets we chose directly challenged this distinction; however, there were occasions where a writer referred to their condition as an illness rather than a disability. Cynthia Hogue did this in part because she was responding to work by Virginia Woolfe essay “On Being Ill” and so she had to toggle between vocabularies.

As with any identity politics, there is always this debate about separatism versus integration: shouldn’t the aim be not another category (or genre) but securing inclusion (or representation) is all anthologies? How do you position Beauty is a Verb in this debate, or does it even engage it?

We have heard disability referred to as another category we don’t need many times, and this strikes us as another version of the abled resisting to give people with disabilities equal rights, employment, and presence in American Society. In a time when over 70% of people identified as “having disabilities” by the government are unemployed, disability is clearly a category that has to make itself heard. It is also worth remembering that people with disabilities only secured legal recognition of their full civil rights with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. We see disability strongly as a social problem not a personal problem; which is why we wish foundations would put money into making buildings accessible and having affirmative action for employment rather than exclusively finding a “cure.” Of course, we would like people with disabilities to be included; yet we don’t believe there is a way to secure representation without category.

To relate it back to anthologies, in reading the recent Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry, edited by Rita Dove, which has generated some controversy for appearing in some sense category-driven, there is not one poet who identifies as disabled. Further, there is no mention of Crip Poetics, which has been the most outward coming out of a disability poetics. Similarly, in writing programs all over the country, introductory English classes are geared toward including African American, Ethnic, Feminist, and Queer literature. But— even though many students have a disability—you will be hard pressed to find any essays or literature by disabled writers. On a practical level, we hope the successes of our anthology–and by all indications so far it is very successful— will work to propel some of those poets we have included into those more general anthologies like Dove’s, where we definitely feel they deserve to be.

In short, we secretly—and not so secretly—hope that disability does become a category. We also hope it is one that speaks valuably to other categories, including the work of writers of color and LGTB writers—in ways that increase our real embracing of a diversity that encourages the maximum valuing of all.

Finally, can you comment on that arresting image on the cover?

Isn’t the picture wonderful? We were so lucky the designer for Beauty is a Verb, the amazing Albuquerque-based Jeff Bryan of Alamosa Books found the image by UK artist and wheelchair user Sue Austin on Google. We were even luckier Sue was so nice about letting her artwork be used for our cover. What do we love about her picture?—it’s an intelligent, fearless, challenging, mysterious, and sexy image of disability—what we want our book to be, a (by-no-means-complete) exegesis and a celebration.