Nona Balakian Citation Acceptance Speech

Someone asked me what I was going to use the prize money for, and I said I was going to hire a body double to give this speech for me.

But freelancer taxes are due, so here I am—the real me, in the sweaty flesh.

I realized I’ve never had to give a speech before. I guess I’m not, generally speaking, a winner, and I suppose none of my friends trust me to give wedding toast. But now you all have given me a prize, your trust, and a microphone. Okay great—now you’re all as nervous as I am.

I have an uneasy relationship to “first” discourse, but I feel the need to note that I’m the first Black recipient of this award. I only mention it to explain why I must, if I ever want to go home again, thank my elders first. So I’d like to dedicate this award to my grandmother, Zelda, who taught me how to read.

Okay, NOW I can thank the National Book Critics Circle and the Balakian committee for this tremendous and truly unexpected honor. I also want to congratulate the other finalists, critics whose work I read this year with deep, deep…envy. To Sarah Chihaya, Christoph Irmscher, Lauren Michele Jackson, and Ruth Margalit, it’s a privilege to be in your company.

Another book critic was giving me advice for this speech, and he said—whatever you do—DO NOT get political, DO NOT get hyperbolic about the importance of what we do, no “the role of the book critic during wartime” or any nonsense like that. Excellent advice, I thought. That should be easy enough for me to follow—right? As a critic who mostly reviews Russian literature?

This has been an unusual year for me. Like all book critics, I’m used to getting frantic texts from friends that say “I have an eleven-hour car ride. What audiobook should I download?” I still get texts like those except now they’re interspersed with “What’s Putin’s endgame?” Simple enough questions like “which translation of War and Peace is the best” have been replaced by: “How likely is a nuclear attack?” And you know the answer to that question, by the way is-…the Maude translation. As one professor I know put it: “it’s the only one that gets the horses right, and that really matters.”

I wish I could say these friends were barking up the wrong tree. That I looked up from my copy of Anna Karenina and replied: “ma’am this a Wendy’s.” However, this has been a conflict where language has been at the fore. Putin used the prevalence of Russian-speaking peoples in eastern Ukraine as a pretext this invasion. As a result, anything to do with language has gotten pulled into the conflict quite quickly, including and especially literature.

On March 16, 2022, a Russian airstrike bombed a theater in eastern Ukraine, killing 600 people who were hiding in the basement. Occupying forces covered the damaged façade with a curtain that had the faces of Tolstoy and Pushkin emblazoned on it. Many in Ukraine have responded by rejecting anything to do with Russian culture and language. Across the country, many have emptied their libraries of Russian-language books and sent them to be pulped. Prominent Ukrainian writers and intellectuals have vowed to never write in Russian again.

As I lay out this context, I’m not sure how I worked up the courage to review anything at all this year. With stakes like these, I don’t think anyone could have blamed me for wanting to throw my laptop into the East River. That’s a Dostoevsky reference. This past year, I reviewed books by writers from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—available in translation thanks to some the very people in this room. Many of these were contemporary writers reflecting on the first stages of the invasion, going back to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the proxy war that’s been unfolding in eastern Ukraine since, and Putin’s neo-imperial machinations across the region.

Why, I wondered, didn’t writing about all of this scare me. I’m just a book critic after all. But then I remembered– I’m a book critic. If there’s one thing we can do (and you know, there might only be one thing we can do), it’s write about language. We, as critics, can hear these writers express a longing for the imprecision and indeterminacy of language in their books and know to read that as a rejection of the politicians who have tried to make language determine everything.

I want to thank the National Book Critics Circle again, not just on my behalf, but for instituting a prize for literature in translation this year. I would have no occasion to review these books and comment on the issues they raise were it not for the work of translators who’ve made this writing accessible to English-speaking audiences. Their work has been a constant reminder to me that language is not just a barrier to be broken down, but the rather the most central element of our art, the quality that makes writing a living, breathing thing, worth fighting for.

Thank you.

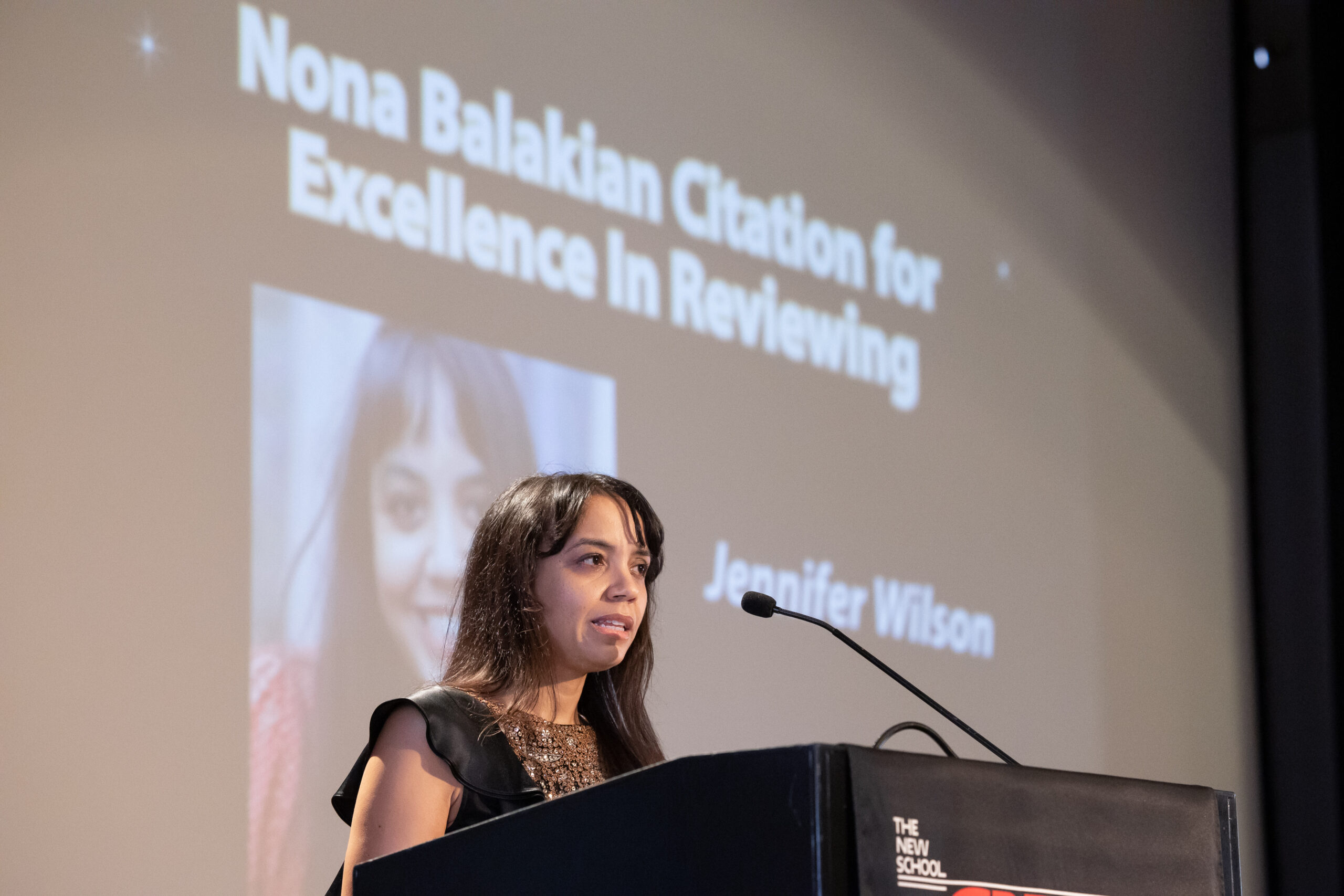

The 2022 National Book Critics Circle Awards, New School Auditorium, New York, New York, March 23, 2023. Photograph by Beowulf Sheehan

The 2022 National Book Critics Circle Awards, New School Auditorium, New York, New York, March 23, 2023. Photograph by Beowulf Sheehan