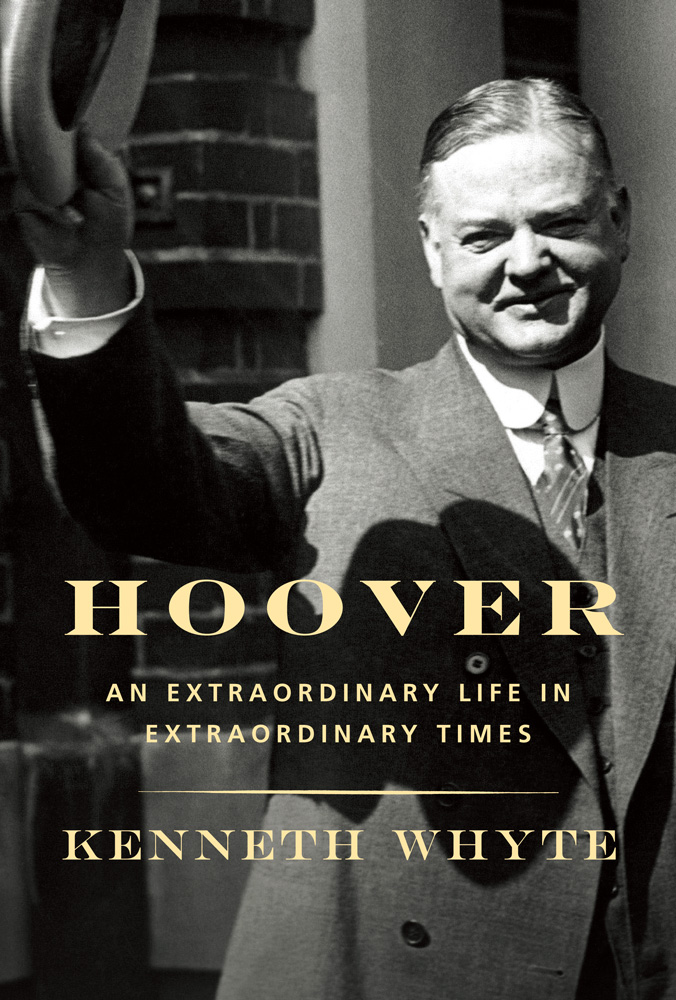

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 15 announcement of the 2017 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Mary Ann Gwinn offers an appreciation of Kenneth Whyte’s 'Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times' (Knopf).

If Herbert Hoover had capped his career with his star turn as U.S. Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s, he would be remembered as an organizational genius and a world-famous humanitarian. Called to action in World War I by the British government, Hoover almost singlehandedly saved Belgium from starving through a massive and unprecedented relief effort. As commerce secretary, he used his genius for massive relief mobilization to aid victims of the catastrophic Mississippi River flood of 1927. But Hoover, a congenital overachiever, could not rest. Buoyed by a wave of American prosperity, he sought and easily claimed the Republican nomination for president in 1928, then won the presidency in a landslide.

If Herbert Hoover had capped his career with his star turn as U.S. Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s, he would be remembered as an organizational genius and a world-famous humanitarian. Called to action in World War I by the British government, Hoover almost singlehandedly saved Belgium from starving through a massive and unprecedented relief effort. As commerce secretary, he used his genius for massive relief mobilization to aid victims of the catastrophic Mississippi River flood of 1927. But Hoover, a congenital overachiever, could not rest. Buoyed by a wave of American prosperity, he sought and easily claimed the Republican nomination for president in 1928, then won the presidency in a landslide.

Then came the stock market crash of 1929 and a worldwide depression that brought the American economy to its knees. Hoover spent most of his single term as president trying, and failing, to rescue the country from economic disaster.

In his new biography, Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times Kenneth Whyte describes what happened next. After Hoover’s thrashing at the hands of Democratic presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, Roosevelt, a ruthless politician, continued to use Hoover as his “all-purpose scapegoat” as he overrode Republican objections to his New Deal suite of programs. Roosevelt eventually achieved political immortality for his leadership during both the Depression and World War II. Today people think of Hoover, if they think of him at all, as the man who failed to help the American people at an hour of dire need. Whyte, a Canadian author and journalist, aims to correct that, and he largely succeeds, resurrecting Hoover in all his flawed complexity.

The son of Iowa Quakers, Hoover was orphaned at age 9 and spent the rest of his youth moving from one temporary home to another. He evolved from his devout Quaker upbringing to become a taciturn, ruthless businessman who accumulated his fortune through some very sketchy maneuvers in international mining. A gifted writer and astute judge of character, Whyte sums up the young Hoover: “He was determined to succeed by any means necessary, subordinating questions of right or wrong to the good of his career and driving himself crazy with his hunger for power and control, his hypersensitivity to perceived threats to his independence and stature, and his overarching need to measure up.”

Then something changed. Hoover, a wealthy man living the genteel life in London with this family, retained the Quaker commitment to public service. When he was called to action by the Brits to help Americans stranded in Europe after the outbreak of World War I, he took charge. Then he was tasked with keeping occupied Belgium from starving. Hoover set a massive humanitarian effort in motion, negotiating with bitter enemies Britain and Germany and pulling off an enormous feat of logistics in feeding the 7.5 million Belgians living under the German occupation. When he returned to America his glowing reputation earned him another mammoth job – managing America’s food supplies once it entered the war. From that point on political success seemed inevitable, but history had other plans.

Whyte’s narrative never flags, whether it’s chronicling Hoover’s hardscrabble upbringing, his hardball business tactics, his political success–then his massive public humiliation and his self-imposed exile. Embittered by his treatment at the hands of Roosevelt, Hoover refused all attempts to return to government service. He hated the New Deal, equating it with “Bolshevism, Hitlerism, Fascism.” He became, as Whyte puts it, “prophet and philosopher” of a new strain of conservatism in American politics. His organizational gifts were sidelined until Harry Truman coaxed him back into the public arena to chair a series of committees tasked with reorganizing the American government.

Throughout these ups and downs, Hoover remains a satisfying, even compelling read. Readers may not agree with Herbert Hoover’s worldview, but after reading this book, they will never forget him.

REVIEWS

Washington Post review by Michael Taube.

The New Yorker: “Hating on Herbert Hoover” by Nicholas Lemann.

David Frum in the Atlantic.