What's your favorite work of resistance literature? That's the question that launches this year's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees at this time of cultural shift. (NBCC Reads from previous years here.) We're posting these in advance of the #WritersResist events to be held on January 15–Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday– throughout the country, including an event on the steps of the New York Public Library. Andrew Solomon, president of NBCC Sandrof-award winning PEN American Center and Trustee Masha Gessen will host; American Poets Laureate Robert Pinsky and Rita Dove will share original “inaugural” poems written for the occasion; and dozens of writers and artists including Laurie Anderson, Mary Karr, A.M. Homes, Michael Cunningham, Jeffrey Eugenides, and others will speak and read on the ideals of democracy.

What's your favorite work of resistance literature? That's the question that launches this year's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees at this time of cultural shift. (NBCC Reads from previous years here.) We're posting these in advance of the #WritersResist events to be held on January 15–Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday– throughout the country, including an event on the steps of the New York Public Library. Andrew Solomon, president of NBCC Sandrof-award winning PEN American Center and Trustee Masha Gessen will host; American Poets Laureate Robert Pinsky and Rita Dove will share original “inaugural” poems written for the occasion; and dozens of writers and artists including Laurie Anderson, Mary Karr, A.M. Homes, Michael Cunningham, Jeffrey Eugenides, and others will speak and read on the ideals of democracy.

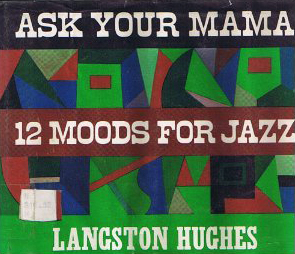

When Langston Hughes began writing his last great long poem, ASK YOUR MAMA (he used all caps for the title and much of the poem) he might have feared that history had left him behind. As the critic Scott Saul has shown, Hughes started it at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, after young white fans rioted when they couldn’t get in: the city canceled the concerts, and advanced black jazz players staged their own event afterwards, with Hughes as MC. It’s a poem whose multiple, braided voices, shouts and laments look to multiple traditions in black American—and not only black American—music-making, from early acoustic blues to boogie-woogie to European art song to the new dissonances of Coltrane, or Coleman. Hughes opens “IN THE QUARTER OF THE NEGROES/ WHERE THE DOORKNOB LETS IN LIEDER” and blazes on through (among many other things) a very Hughesian rewrite on gospel motifs: “DOWN THE LONG HARD ROW THAT I BEEN HOEING/ I THOUGHT I HEARD THE HORN OF PLENTY BLOWING/ BUT I GOT TO GET A NEW ANTENNA, LORD/ MY TV KEEPS ON SNOWING.”

That’s the kind of great stanza you might expect from Hughes, in 1960 or 1925. But there’s much more: ASK YOUR MAMA always asks for more—it is, above all, never satisfied, and it never says just one thing. The repeated title “ASK YOUR MAMA” means “look to your heritage” (if you are black) but also “stay angry,” and also “don’t ask me.” There’s a roll call of eminent African Americans and postcolonial leaders from “JIMMY BALDWIN” to “LUMUMBA” to Blind Lemon Jefferson: the poem is, in part, an excuse to list those leaders. Yet that list suggests that international, revolutionary movements have the momentum, while black and white American society, left to itself, might indeed (as Hughes implied twelve years earlier) “explode”: “THE TOLL BRIDGE FROM WESTCHESTER/ IS A GANGPLANK ROCKING RISKY,” “ON THE BIG SCREEN OF THE WELFARE CHECK/ A LYNCHED TOMORROW SWAYS/ WITH ALL DELIBERATE SPEED.” (Italics alongside those lines reads, in part, “the metronome of fate begins to tick faster.”)

ASK YOUR MAMA explores Hughes’s frustration with readers—white and black—who thought of integration as the end of history, as the ultimate goal, and with Americans who think “America” is the best name for what we most value, who think “America” can do no wrong. “ONE SHOULD LOVE ONE’S COUNTRY/ FOR ONE’S COUNTRY IS YOUR MAMA”—that couplet leaves many rooms for many tones, from sarcasm to quiet insistence to flailing resignation. What do you think of your country and where it’s headed now, Mr. Hughes? Senator Reid? Mr. Brown? Mr. Rice? Mr. Garner? YOUR MAMA.

With its indications for musical accompaniment (“ Maracas continue rhythms”), its back-and-forth between quatrains and shouted free verse, ASK YOUR MAMA has to be Hughes’s attempt to hear and respond to the first notes and strands of free jazz, of the Black Arts Movement, of 1960s radical consciousness, of decolonization, with resolute hope. But it’s also a poem about what to do, what sounds you can make, and what art you can assemble, out of frustration and rage at the frayed end of what looked like a multiracial, forward-looking, American project in politics and the arts, whether it’s one festival in one city, or the early (and most multiracial) phase of the civil rights movement, or the Obama administration, or the rule of law.

The sound ASK YOUR MAMA makes—raucous, fed-up, agitated, uncertain— is the sound of “what do I do next?” and the sound of “what do we do?” from a poet who knows who “we” are—in this case, African-Americans and Afro-diasporic listeners—but not, exactly, where he belongs. And it’s the sound—or sounds—of resistance: not just to any particular politics, not just to any explicit artistic program, but to anyone who thinks they know just what’s coming next, and what we can do. It’s a poem whose metrics, whose organization, even whose typography stays upset, and keeps us uncertain, because certainty is the enemy of politics, and the enemy of hope. To anybody who thinks things will surely get better, or surely get worse; to anybody who wants to tell a group or an individual that their anger doesn’t count; to anybody who hasn’t noticed the danger signs in the news or in the right streets, and to anybody who thinks that only their program will do, Hughes’s polyphonic phrases have a message. What do they tell you? ASK YOUR MAMA.

Steph Burt is a poet, literary critic, and professor of English at Harvard University, and author of the essay collection Close Calls with Nonsense (Graywolf Press, 2009), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and, most recently, of The Poem Is You (Harvard University Press 2016).