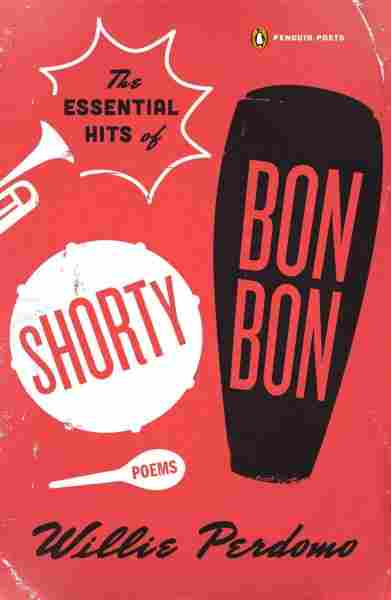

In the days leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Gregg Barrios offers an appreciation of poetry finalist Willie Perdomo's “The Essential Hits of Shorty Bon Bon (Penguin Books).

In his new collection poet Willie Perdomo weaves poetry, music, and song into a long jam session (a descarga) that chronicles the brief, unsung life of Shorty Bon Bon, a Puerto Rican percussionist who came to the mainland of Manhattan and found his destiny in the music.

The telling is not unlike a reporter on deadline, fashioning an obit about the night the music died. It takes the form of a live recording session with Perdomo bearing witness to what will be Shorty’s last set: “Once the red light flicks on there is no time / to fix mistakes, Poet.”

The poem “How I Came to My Name” is the opening riff, as the young ambitious tyro learns to fight for the music – not unlike the recent film Whiplash: “Palmieri points his first finger / Straight at my heart & says, / You – Shorty bon bon blen /Bien bip bap – don’t squeeze / Too hard, this ain’t rehearsal. / Don’t go promoting half-truth…. / don’t ask for a / Thing, don’t flinch – stop only / in heart-stop & when you feel / Like it’s on the money – jump.”

Told in the jazzy, bebop beat lingo and lexicon, the language rhythms take on a life of their own, and soar, giving rise to the history behind the origins of Latin music when “the salseros, the real life soneros, / the palo-players that gang-busted / dancehalls with fish-crate yambú; / the tumberos who recorded the earth / in clay jugs.” And, later on the mainland their off-springs become quintets – “who changed their names from Joe Loco to Joe / Panama, Joe Ponce to Joe Cuba… /who vamped it up and whistled evil / out of garden their Africando / was so hot, co-op boards had to / call the police.”

In a “selfie ode,” Shorty relates in hip-hip swagger: “How Cool Was I”. “So cool – I chased God like he was on the run. / So cool – that when Puente heard my speed I made him bite his tongue. I’m saying I made the Mambo King bleed.” Later, Perdomo performs a CSI autopsy on Shorty to see what makes him tick: “If you were to cut Shorty open out would spring Rose like a wind-gusted boulevard, a rooftop call for love and war, a late-night radio dedication, a gat to your chin, a boy with a flag, a dragon chase, a notebook full of dreams and number…”

And what would the life of a musician be without a love jones? In Shorty’s case, it is Rose, the singer with the band. Perdomo evokes those smoky dives and clubs in noir B-movies. The poem “The Soul May Better Understand” opens with the siren on the bandstand. “Rose’s first note carried Beautiful black faces, Guts & Apocalypses… / One night she invited Wrong & Right / Backstage to a fair one – / Beat the ditty out of both… / Just imagine, Poet: Your house is burning down / and there’s no fire escape / To bust free of form.”

Later, Rose confesses the kind of love she desires from Shorty: “Be crystal, / crash into me / like a new star, / like the ground / rips open just for us. / Be gentle when you / talk, pretend you got kicked / in the head by a mule / and when you lost vision, / the first thing you heard / was my song.”

Perdomo captures their bittersweet breakup succinctly: “Candlelit, she disappeared the way she appeared – / No encore, no applause.” Devastated, Shorty returns to the Boricua motherland: “In the dream, I was in Puerto Rico. It was raining and headless worms inched along the dates of my tombstone.”

The dream is fueled by a hysterical, historical high: “The weed so good / you swear that La Niña is on the horizon… / When Columbus steps ashore, you call him / Negrito, you say, Take off the brim, lose the / Doublet, get rid of the girdle, –it’s hot, bro.”

In the end, Bon Bon’s demise arrives not as a crescendo but a gentle “no words, no air.”

This collection may well be Perdomo’s masterpiece. He has created a soulful, poetic narrative of a man who lived, loved and died for the music. His choice of poetic forms from scat singing, décimas, free verse, rap and sonnets is both imaginative and dope. If his use of hip-hop verse, reminds you of Manuel Lin Miranda’s reimagining of history in his musical hit Hamilton, it is an early clue in the new direction Latino writers and playwrights from Piri Thomas and Oscar Hijuelos to Richard Blanco and Junot Díaz have brought to the literary table that is both original in its vision and language and in the telling of our collective history to a new diverse generation of readers and audiences that are an integral part of this crazy quilt that we call America in the 21st century.