Thanks to The School of Writing at The New School, as well as the tireless efforts of their students and faculty, we are able to provide interviews with each of the NBCC Awards Finalists for the publishing year 2013.

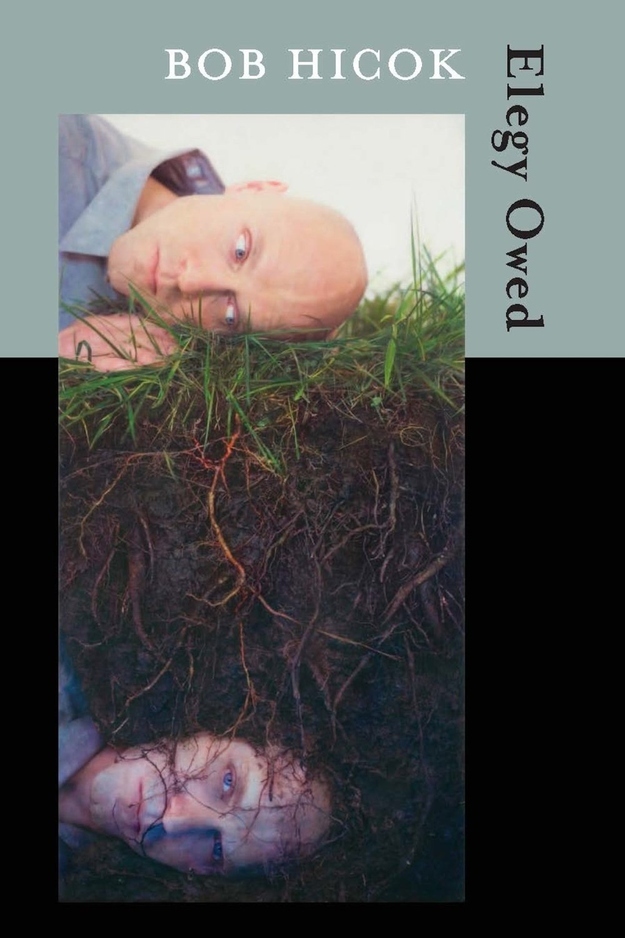

Ben Fama, on behalf of the School of Writing at The New School and the NBCC, interviewed Bob Hicok, via email, about his book Elegy Owed (Copper Canyon Press). Elegy Owed is among the final five selections, in the category of Poetry, for the 2013 NBCC awards.

From the Publisher: When asked in an interview with Gulf Coast, “What would Bob Hicok launch from a giant sling shot?” he answered, “Bob Hicok.” Elegy Owed, Hicok's eighth book, is an existential game of Twister in which the rules of mourning are broken and salvaged, and “you can never step into the same not going home again twice.” His poems are the messenger at the door, the unwanted telegram—telling a joke, imparting a depth of longing, returning us finally to a different kind of normality where “the dead have no ears, no answering machines / that we know of, still we call.” There is grief in these poems, but it is a grief large enough for odd awakenings and the unexpected, a grief enlarged by music, color, and joy as well as sober wisdom.

From the Publisher: When asked in an interview with Gulf Coast, “What would Bob Hicok launch from a giant sling shot?” he answered, “Bob Hicok.” Elegy Owed, Hicok's eighth book, is an existential game of Twister in which the rules of mourning are broken and salvaged, and “you can never step into the same not going home again twice.” His poems are the messenger at the door, the unwanted telegram—telling a joke, imparting a depth of longing, returning us finally to a different kind of normality where “the dead have no ears, no answering machines / that we know of, still we call.” There is grief in these poems, but it is a grief large enough for odd awakenings and the unexpected, a grief enlarged by music, color, and joy as well as sober wisdom.

Ben Fama: In an elegy one would seemingly need to confront religion, and you do, setting yourself apart from those who might be called “believers.” I'm thinking here of lines such as “Those who believe in eternity will sing,” or “My heart is whatever temperature a heart is in a man who doesn't believe in heaven.” The speaker seems to have a stable relationship with God, who appears as a character throughout the book. Was writing this book particularly spiritual for you? Is religion or maybe just our county's culture of religion something you think about a lot?

Bob Hicok: All existence is spiritual. We embody the mystery of creation, the unknowing of how we got here, by being here. Writing–any activity that tilts toward meaning–tugs that embodiment toward consciousness. It's hugely corny but hugely necessary to say that I think the job of poets is to keep reminding themselves and others of the wonder that anything is here, versus nothing. But religion–religion drives me nuts. Religion collides with spirituality in a great and unfortunate particle accelerator sort of way and tends to smash the hell out of wonder in its drive–its fetish–for certainty. My relationship isn't with God but what God stands for–that somehow, all this happened. God—my God—is that somehow.

BF: There is a refrain in the book of the idea that writing can do something when someone goes missing from life (that is painting it in broad strokes). What is this thing it does?

BH: Resurrects. Holds. Gives flesh to. Writing–these little swirls and sticks–are the bodies we give our thoughts, the way (a way) we send them out into the world to be met and held by other minds. When the writing is about some gone soul, or just the notion of that goneness, that loss, it seems an even more tender exchange, the abiding ineffable–that mystery stuff I spoke about above–accentuated and torqued by the intense missing of a person who embodied that mystery, who gave it hair and hips and kisses.

BF: You vary from lyric forms to prose, occasionally using narrative in lyric form. Between lyric and prose, do these styles, which seem very different to me, fulfill different urges for you? I remember years ago, shuffling among literary journals, and I found a short story you had written, which I can't recall the title of or the publication it was in, more so the feeling of it, though the character was able to turn on light bulbs with only his hands, and he was standing in a field performing this to please the other character. Apologies here for what I am misremembering.

BH: What tends to happen is I'll write a kind of poem for a few days and then sit down and feel the limits of that kind of poem and want to move away from it. I love the surreal but the surreal, at its edges, turns cold, and that coldness might push me toward narrative. Narrative in its details can be warm and wonderful but tends to push out figuration and therefore leans toward plainness, which might push me in a more lyrical direction. Lyricism can be a rush for the tongue but easily gets tangled up in and distracted by pretty, and that might push me toward the inventiveness of surrealism. They all work and they all don't. The mash and movement between them has been a wheel in my work, and an ongoing source of disquiet. I wish I felt more settled, in a way, but I don't. I think I'm happiest when they all show up.

BF: Since we are interviewing in regards to your nomination for the NBCC, I want to ask, perhaps indulgently, about your life as a writer. Much has been made that you once ran a successful automotive die design business when you lived in Michigan, where you spent most of your life before moving to Virginia, and I can see why…it is an unexpected biography for a poet. How have things changed for you in your writing practice as your career has shifted? When I studied with you at Virginia Tech, you' always stressed discipline—and in a previous answer you mentioned cycling between modes as you followed your instincts in your day-to-day writing. Can you tell us a day in the life?

BH: In one respect nothing has changed. I wrote every day before and do so now. But I'd reached a limit. The work I did demanded a lot of time–a typical week was 60 hours. I'd done both for decades but was running out of the zip it took to do so.

Day in the life—I could tell you but the telling would put you to sleep.

BF: A poem that stood out to me from the others in your book (for its political content) was “Obituary for the middle class.” In this poem, which I read as dystopian and sweet, the middle class has imploded, and life as we currently live it has become implausible, a fairytale. The poem says, about our future generations: “they will be spared money.” This is something I think about a lot, especially as I see contemporaries of mine with advanced degrees struggling for months, even years, to find jobs that will allow them to maintain a baseline of financial stability. What was it you were seeing in the culture that prompted this poem?

BH: What everyone's seeing–trouble. My family–there are seven kids—was middle to upper middle class. Out of the seven, one might do better than my parents did. Fundamental assumptions about the nature of our lives, such as upward mobility, no longer apply. Simply put, the jobs aren't there. Manufacturing has been hollowed out over a period of decades, but it's the nature of rot that it takes a long time to show. It's showing now. Too many jobs have been lost in too many sectors over too long a period of time for the effects to be patched over. A poem in my previous book begins “My sister's out of work and my brother's/out of work and my other brother's/out of work”–that's what I was and am seeing. These are people with advanced degrees who've all had to scale back what they thought life would be. Unfortunately, the political and philosophical mood of the country is more hunker-down than reach-out. Is this the cheery portion of the interview? Let's call it the interlude of doom.

BF: I like that idea, the interlude of doom, though I certainly didn’t intend to send us in that direction. Since we are here though I want to ask a question about the shootings that occurred at Virginia Tech. I was taking your course there at the time when this happened. It was my fifth year and I was finishing two degrees. VT is a tech school known mostly for football and engineering, and I had a troubled relationship toward that culture of it. In the end, I was saved by the New River and the communal landscape of those living their lives in the valley of the Blue Ridge Mountains, spending leisure time by the New River itself. By association, or maybe projection, I am able to fill my need for this inside your poems. After the shootings I remember an email you sent out letting us know our options as students, and that the shooter had been a previous student of yours. It was April then, and I remember you wrote how you wanted to “walk into summer and keep going.” Nothing sounded better, so that's what I did, and I moved away a month or so later. Instructors didn't have the option not to return to class after the shootings. In the seven years since this event happened, invariably at job interviews, I am asked what the experience was like. This question makes me extremely uncomfortable, I admit, but I've always wanted to ask you how things were for you that summer, and after, as things slowly came back together?

BH: Bit of a cliché, but I wrote my way through it. This happened pretty much immediately and went on for several months. That was it–that’s what I wrote about. Outside of the writing, my abiding feeling was failure–that we’d failed these kids and their families. It’s not rational, really. But those deaths are such a perversion of the normal order–parents die first and no one should die because they went to college. Those feelings have stuck. Oddly, though, being on campus pulls me away from that. I’m surrounded here by young people who need to, who want to get on with their lives. The momentum is forward and campuses are eternally young.

BF: I wanted to end by asking about influence and interests. In your breathtaking title poem, “Elegy Owed,” there is a ravenous and unconditional love, and I say “breathtaking” because there is a moment when the speaker stops breathing, recalling another famous elegy, Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died.” You’ve mentioned before that he’s a writer you like. All artists and writers have to deal with an incredible amount of history and achievement that has come before them in their field, how do you relate to your influences, and do you feel a responsibility to them?

BH: This question is difficult because I didn’t really start reading poetry until I was in my 30s. My influences were musicians, not poets. Take O’Hara (please)—I came across O’Hara long after I’d cut my teeth. And what I do is so far removed from the music I listened to that no, I feel no responsibility to Tom Waits or Rickie Lee Jones. Same with poets I like. Or maybe the way I feel responsible is that good poets make me want to try harder–that’s certainly the case. I always have books or poems around that make me feel thrillingly inadequate. I kind of like the way writers rub off on me now. It’s quite conscious, and there’s no danger of infection, just warmth.

Bob Hicok’s This Clumsy Living won the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry from the Library of Congress. Recipient of five Pushcart Prizes, a Guggenheim, and two NEA Fellowships, his poetry has been selected for inclusion in eight volumes of The Best American Poetry, including The Best of The Best American Poetry. Hicok is currently an Associate Professor of English at Virginia Tech.

Bob Hicok’s This Clumsy Living won the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry from the Library of Congress. Recipient of five Pushcart Prizes, a Guggenheim, and two NEA Fellowships, his poetry has been selected for inclusion in eight volumes of The Best American Poetry, including The Best of The Best American Poetry. Hicok is currently an Associate Professor of English at Virginia Tech.

Ben Fama is the author of Fantasy (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015), Mall Witch (Wonder, 2012), and the chapbook Cool Memories (Spork Books, 2013). He lives in New York City. He is currently an MFA student at The New School.

Ben Fama is the author of Fantasy (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015), Mall Witch (Wonder, 2012), and the chapbook Cool Memories (Spork Books, 2013). He lives in New York City. He is currently an MFA student at The New School.