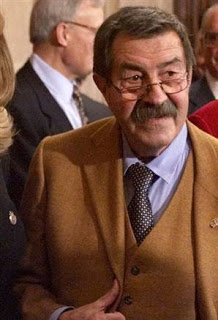

On July 5, 2007, Critical Mass published John Freeman's interview with Günter Grass, whose memoir Peeling the Onion, which described his journey to becoming a writer, his infatuation with the army, and his enlistment in the Nazi troops and belief in its cause, had just been published. Grass's new novel, The Box: Tales from the Darkroom, carries the story forward, in fictional form.

On July 5, 2007, Critical Mass published John Freeman's interview with Günter Grass, whose memoir Peeling the Onion, which described his journey to becoming a writer, his infatuation with the army, and his enlistment in the Nazi troops and belief in its cause, had just been published. Grass's new novel, The Box: Tales from the Darkroom, carries the story forward, in fictional form.

Peeling the Onion is a powerful, odd, beautifully structured book about the fallibility of memory and the distance that puts between an almost elderly elder statesman and the young man he was six decades ago. However one feels about the way Grass has made public his time in the Waffen SS — he says he spoke of it in the '60s and no one in Germany paid it any attention — the measured, sometimes mysterious way he peels and peels away at the self he once was is riveting. I asked him a few questions about memory when he was in New York the other week and here is what he said:

Q: Is it extremely important for Germany to remember that memory is imperfect?

A: I think it is important for every country. Defeat was so absolute, there was no chance to go back and ask questions. My generation has had to write about it – it was the way out. And I got to recreate my hometown, this lost city of Danzig, in my words. That’s one of the possibilities of fiction – to look back, and to recreate something you have lost.

Q: In some ways, this feels the most naturalistic of your books — there are no three year old prodigies, no talking animals. Was it strange to write in this fashion for you?

A: Well, this book works on several levels of memory – at one point, it is the story of this boy who wanted to be an artist, who through all the changing times and difficulties, the destruction of Germany after the war, continues. The other side is all the books I have written later are founded on these early years – so there are many different time levels. It’s not very naturalistic, it’s very open form.

Q: Why did you decide to put drawings into this book?

A: That’s mostly when I hand in the manuscript, I have sketches. In the first version was written by hand, very old fashion, the beginning of a chapter, the sketches, would help the situation. Then when I finished this book I was concentrating on the audience. This happens very often to me –

Q: Throughout your entire career you have been the source of or focus of controversy — does this ever make you question whether you should continue?

A: But I can’t help, I have to go on, I have to write the next book. I was astonished when I wrote Too Far Afield and that was controversial, but now all the critics are silent…but at the time it arrived it was controversial. There is always the reaction of the critic, but the readers are different – this book got so many letters from my generation, old people, and also young people – people saying to me I was finally at last able to say I was able to talk to my children about my time during the war. The same of the young people – they said it was the first time our grandparents talked to us about our time during the war. And I think this is a marvelous reaction – if they are reading the book and able to speak out.

Q: At one point you say “my silence pounded in my ears” – you must feel a certain relief as well.

A: Yes, of course, it was for me necessary, and in a way it was also helpful to write this book – in the ‘60s I spoke openly about my time in the Waffen SS but nobody takes care, and afterwards I didn’t speak about it for year to year I got more news about the crimes done by the Waffen SS, so it was necessary to write this book. But much more for me to speak of all these questions I didn’t ask in my book about my uncle who was shot down during the beginning of the war, or about this boy who didn’t touch the rifle, but they are much more painful to me than my short time in the Waffen SS – like many of my generation I didn’t speak out.

Q: You have basically spent your entire career writing about this period — do you ever wonder if you would have become a writer without that experience of war-time and post-war Germany?

A: From seven years old I wanted to be an artist – without this German past, without these two lost wars, without the blemish in every family, and all this crime, and this burden of guilt, we had no other choice as an author then to write about it.

Q: Is that a point you were making in My Century?

A: The same question I could ask to every country, some months ago I was in Spain, now in Spain very late begins a discussion of a civil war in the Franco time. You will have the same discussion here in America about the Iraq War and the lies and all these things – it needs sometime. The difference is this kind of war we are engulfed in, really happened in Germany, everybody was touched – in the US Vietnam, Iraq is far away. There is only a group of soldiers who are coming back with the trauma, all their life.