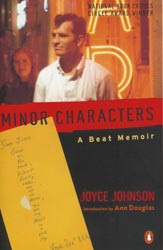

I n Critical Mass's ongoing “In Retrospect,” in which contemporary critics revisit former winners and finalists for the National Book Critics Awards, Vince Passaro, a critic and author of “Violence Nudity Adult Content: A Novel,” considers Joyce Johnson's “Minor Characters.” (Updated from August 20, 2007.)

n Critical Mass's ongoing “In Retrospect,” in which contemporary critics revisit former winners and finalists for the National Book Critics Awards, Vince Passaro, a critic and author of “Violence Nudity Adult Content: A Novel,” considers Joyce Johnson's “Minor Characters.” (Updated from August 20, 2007.)

Much to my chagrin, I am walking around now, at 50 years of age, in the new millennium, when Manhattan has for a good while been transformed into the most densely populated and expensive shopping mall/casino complex in the universe, thinking somehow the year is actually 1957, and apartments are $45 a month, and you can work part time here and there and get by okay, and meet your friends for drinks at the Cedar Bar (not to be confused with the Cedar Tavern, which has also ceased to exist, we don't want to get our lost-forever touchstones mixed up) and you can write and paint and make music, secure in the knowledge that a life dedicated to art, even unrecognized, is a life of honor, and ideas still matter, and there is in the air a collective yearning for beauty and for meaning.

As Bugs Bunny once said, of an obstinate and easily baffled bull, “What an ultramaroon.”

In part I blame Joyce Johnson’s “Minor Characters” for this mental disease, which has led to so man of my delusional and bad decisions. I read “On the Road” at 18 or 19 years of age, and by my early 20s I was wise enough to know it was a piece of high American romanticism and reflected reality only obtusely, in the way of Walt Whitman’s accounts of his wanderings on the waterfront, gazing upon the stevedores — which is to say that it reflected reality at a beautifully distorted, highly entertaining angle that would never be replicated. “Minor Characters” however — like William Burroughs’ letters from that period – dealt in real life, in darkness and want. It had an overbearing mother and an only half-rebellious youth, who one suspected suffered more than the fully rebellious or the fully conquered. It had bad jobs and sad nights and rents to be paid and lovers taken and lost and writers who were struggling to write and painters struggling to paint. The life Kerouac imagined had no struggles at all. Even his sadness felt then (we knownow it wasn't) like passing sadness, it glittered beautifully and transiently, like sunlight on water near end of day.

Johnson herself (I was fortunate to take a class with her in graduate school) has no such illusions as mine; she knows what’s past is past. The other great strength of “Minor Characters” is its intelligence, the combined skills of having the truth well in hand and presenting it artfully, in a clear and muscular prose. Her youth in the Village coincided with a deep and powerful moment in New York’s swollen literary history; there will be no others even half as rich in my lifetime, and Joyce Johnson is its most reliable witness. The “minor characters” of the title are, of course, the women in those men’s world. There is a startling scene near the end of the book when Joyce sees them down the street, and thinks of their beauty and their obliviousness (or so I remember the moment now). The genius of the book in part was a turning of the tables in which Johnson shows you that not the women but the men are beautiful unworldly romantics, easily broken. I can see the truth of her point in myself, even now. Much as I might in later years have written off Kerouac, it is still the romantic disease that kept me a believer long past the day when my illusions were affordable – no woman would have held onto such a childish and impractical idea for so long. Certainly not one as smart as Johnson.