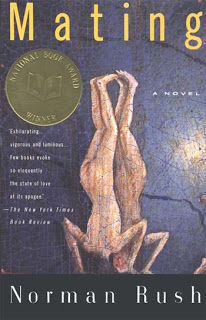

A Theory of Everything — Norman Rush's “Mating”

The following essay by NBCC member Scott Esposito on Norman Rush's 1991 fiction finalist Mating, is part of the Critical Mass In Retrospect series in which contemporary critics reevaluate NBCC award winners and finalists since 1975. Mating is a novel that continues to strike readers today as a profound meditation on love. Rush discussed his narrative challenges at the PEN World Voices Festival last month in a panel cosponsored by Guernica Magazine and WNYC's Jerome L. Greene Performance Space. Video here.

For as long as I've been a college graduate, a return to higher education has held out the promise of something more exciting and meaningful than what I gently folded myself into shortly after graduation: an uninspiring life safely ensconced in America's middle class. Though it may be only an illusion (and a costly one at that), a return to school is at least plausibly more purposeful than office work. In addition to “go back to school,” there are two other paths of escape that I can identify; they are: “live abroad” and “fall in love.”

The unnamed narrator in Norman Rush's outstanding novel Mating (nominated for a National Book Critics Circle award in 1991) takes up all three of these. When the novel starts, she has gone back to school and gone abroad. Though writing a dissertation in Botswana may be a step up from Ronald Reagan's '80s (“like being stabbed to death with a butter knife by a weakling”), the narrator is nonetheless finding graduate school and ex-pat society lacking. Specifically, her theory that the reproduction rate of gatherers is related to their food supply is going nowhere, and the Americans living with her in Botswana's capital, Gaborone, are like a petit version of those she fled from.

So much for the first two means of escape. At loose ends, the narrator heads to Victoria Falls and has a revelation:

I think the falls represented death for the taking, but a particular death, one that would be quick but also make you part of something magnificent and eternal, an eternal mechanism. This was not in the same league as throwing yourself under some filthy bus. I had no idea I was that sad. I began to ask myself why, out loud. . . . One sense I had was that I was going to die sometime anyway. Another was that the falls were something you could never apply the term fake or stupid to. This has to be animism, was another feeling. I was also bemused because suicide had never meant anything to me personally, except as an option it sometimes amazed me my mother had never taken, if her misery was as kosher as she made it seem. There was also an element of urgency underneath everything, an implication that the chance for this kind of death was not going to happen again and that if I passed it up I should stop complaining—which was also baseless and from nowhere because I'm not a complainer, historically. I am the Platonic idea of a good sport.

She does pass it up and responds to her brush with death by going at love, big time. She briefly affairs with three men, all of whom turn out to be wildly inappropriate, but for delightfully different reasons, and then meets a fourth with whom she connects: He is Nelson Denoon. He is an utterly brilliant sociologist (even the Marxists grudgingly grant him approval). He builds things that most people wouldn't even have the ability to think up. He has founded his own utopian, solar-powered, female-dominated colony in the desert.

He is worth almost dying for. Showing a great deal of initiative, the narrator treks, alone, for three days through the Kalahari desert, eventually flopping down at the gates of Denoon's colony on the brink of death. The two fall in love, but before the end of Rush's novel both the colony and the relationship will have fallen apart.

What makes this bulky novel that proudly flexes its erudition so compulsively readable? First and foremost is the narrator, a splendidly conflicted voice whose depth and detail feel like arabesques upon arabesques built to infinity. This is Emerson's multitudes at their finest.

Her number one conflict revolves around men. The narrator is smart, independent, and modern enough to knows just what a catch she is (“My preference is always for hanging out with the finalists”) and vocalize laments like “Why even in the most enlightened and beautifully launched unions are we afraid we hear the master-slave relationship moving its slow thighs somewhere in the vicinity?” Moreover, she respects herself enough to hold out for intellectual love (instead of the debased, physical kind). And yet, she finds fulfillment in that most stereotypically feminine of ways, by following a man. Just the kind of personal dilemma that could fill a book.

It must be said that presenting a 500-page novel solely in the first-person is a very dangerous enterprise—few writers can create characters compelling enough to pull it off—but by the end of Mating I was not only willing but eager to stay with the narrator for another 500 pages. Rush has said that she was the product of great “hubris” on his part; perhaps then it's time to rehabilitate this maligned concept. Though the narrator's language is often scarily erudite (“Tsau, the omphalos of my idioverse”), Rush expertly brings it to bear to create a mind that we can follow for quite a while.

Partly this is due to the narrator's capacity to invent compelling theories to explain herself. Look back at that passage where she's contemplating death before the falls: in three sentences she's expressed three plausible, non–mutually exclusive theories about why the falls make her feel sad, and then we suddenly vault to a speculation about suicide that hinges around her mother, pause for a moment as the falls sublimate her need to do something with her life, and end with a nice, safe insult. Who wouldn't be taken with a mind this fecund? Though the falls scene is one of the book's finest, throughout Mating the narrator is similarly complex and insightful.

Rush's narrator also works because she is so human in her anxiety—though she's smarter than most of us and off on an African adventure with a famous intellectual, she's still someone we can identify with. For instance, on an early date with Denoon the narrator hopelessly shames herself by using the wrong end of an experimental chemical toilet that Denoon invented. The scene might have been just another lukewarm anecdote viewed at arm's length, but what makes it ignite is the narrator's own self-excoriation, which is far harsher than anything the rather relaxed Denoon can dish out. Anyone who has ever been in love has known this self-scrutiny, and the narrator is so harsh that we even feel like we've got a little something on her. She may be fluent in Setswana, but at least we wouldn't go all to pieces like that.

And, lastly, Rush's narrator works so well simply because Rush is an amazing writer. (It's just not right that a book that includes as much Latin as Mating is so easy to read.) Here he is, for instance, expressing the feeling of loving abandon:

For me love is like this: you're in one apartment which you think is fine. . . .You're happy there and then you go into the next apartment and close the door and this one is even better. And the sequence continues, but with the odd feature that although this has happened to you a number of times, you forget: each time your new quarters are manifestly better and each time it's breathtaking, a surprise, something you've done nothing to deserve or make happen.

Continually, Rush finds ways to make his ideas palpable, his people and places immediate. The book is encyclopedic in its environmental detail. Though Mating never shrinks from intellectual difficulty, this is balanced by a fully fleshed world and a compelling plot that one can simply enjoy without ever needing to engage the ideas.

So all praise the narrator, for she is great; but there is another part of this story beyond the narrator and relationship with Denoon: What of the woman-dominated colony in the desert? What of this place that is so intricately imagined—and so believable—that one wonders whether Rush at some point had half a mind to form one himself.

What has Denoon built? He has built a utopia, one based on a couple of radical ideas. To start, he imports most of the good parts of the last best political theory (the one we've done a pretty good job of finding the faults with) and then goes us two better: First off, Denoon's colony will cut back on avaricious disputes over resources by being powered by the one thing the desert never runs out of: sunlight. (There's also a scrip-based exchange system to help mitigate other resource-sharing conflicts; like I said, Rush has definitely thought this out ) Secondly, the colony will fix another defect of modern democracies, patriarchy. Denoon's colony gives women all the power; it aims to discover “what women are or what they might be if they were left alone.” By Denoon's logic, this will be better than what Reagan et al. can give.

As a political theory, matriarchy isn't that bad. First off, there's the fact that, as male rule has more or less been the norm everywhere as long as humans have been writing down their history, a sense of fairness dictates that the next 4,000 years or so should invert things. At the very least, after all the hare-brained regimes tried out in the 20th century it deserves a shot. There's also the fact that patriarchy doesn't have the best track record. Certainly it hasn't been a complete bust, but there have been enough problems along the way to make it at least plausible that a matriarchal society would do better.

Though matriarchy has much to recommend it, Denoon's colony is a utopian community in which the founder takes things a bit too far (a 50-50 power-sharing arrangement seems more fair), so you can probably guess what happens next: Denoon's colony comes apart. From one end, the women are beginning to get a bit tired of living under their benevolent, male ruler. There's increasingly less subtle hints that it's about time for Denoon to leave. (And the question can be asked, Is Denoon's colony even a matriarchy until he leaves it?) Then there's the other end. Men and guns begin to infiltrate the colony, and eventually they spoil it before the women can force Denoon out. Just as Denoon's colony is coming apart, so is his relationship with the narrator.

To Rush's credit, the fall of Denoon's colony isn't meant to give us a message. Rush is far too smart to think that crushing this utopia will offer us any insight into the fallibility of humanity that we don't already have. Rather, what Mating is at this point is a tragedy; Rush is simply showing us what happens when two people lose the most important parts of their world. And, finally, when the devolution is all over, the ways in which our two leads respond to these losses will act as a crucial cap to this novel.

But let's pause here for a moment. It would take an uncommonly dull reader not to notice some kind of connection between Plot A, the woman who throws herself at a man in spite of her self-respect, and Plot B, better living through matriarchy. Clearly, there's a link, but what exactly is the connection? Why juxtapose these two stories? On this Rush is thankfully silent, and those who read this fine novel should have a fine time speculating.

Here's where I see the two coming together. Mating is the story of a search for purity and of the harsh lesson that purity is not for us in this world. Look at the narrator and Denoon: first they leave their (fallen) home country; and then when their adopted homes come up short they take themselves ever farther away, walking out into the desert to live in a rarified society of their own design. Exhibiting the best of American Puritanism, they fundamentally don't believe in reforming fallen creatures; they're looking for the elect, and for those who don't measure up, well, tough luck.

Not incidentally, Denoon and the narrator both find their visions of purity in the opposite gender. For the narrator, this purity is Denoon, the man who will give her intellectual love, a perfect relationship existing in the rarefied world of the ideal. For Denoon, purity is a society ruled by women, one immune to the taint of male aggression. (It's no coincidence that Denoon had an abusive father.)

Both the narrator's and Denoon's images of purity are fundamentally logical in nature, and the great irony of this is that both happily believe in their logical ideals while in the steel grip of that most irrational of creatures, love. They're a good match for each other, but do they have the least idea of why? Doubtful. Recall the busted thesis that starts the narrator out on her quest for purity at the beginning of Mating: the overflowing amour of the gatherers doesn't pay heed to logic. As their resources dwindle, so should their reproduction rates; but they don't. Knowing this, why should the narrator expect her own love to follow the logical peregrinations plotted out in her mind? Why should Denoon not expect his society to one day fall prey to ills just because it's ruled by women?

These two incredibly smart people have paid fealty to the god of the intellect for so long that they have hobbled themselves by forgetting that love is not logical. The narrator is roughly of the age when the steadfastness of youth begins giving way to an understanding that this world requires compromises, and I think this is no coincidence. As for Denoon, he should know better. Maybe it's the effect of too many years in academia, or maybe some people are just idealists through and through.

The fall is swift for these two, the consequences profound. Denoon heads off into the desert by himself, comes back battered and in possession of a singular, mystical experience (or was it just dehydration?). Dressing all in white, eating no meat, virtually comatose, the hyper-purified Denoon makes Ghandi look like a rabid lion.

He now wants to marry the narrator, and, logically speaking, its arguable that this precisely is the kind of perfectly gentle, intellectual man that would satisfy her ideal love; but can any of us blame her at being revolted by the new Denoon? Her belief in purity broken, the jaded narrator ships herself back to the States, where she ends up making a tidy sum in the lecture circuit by discussing the time she spent with Denoon in his colony and becoming a fine academic.

The end holds out the tantalizing possibility that Denoon and the narrator are going to give it one more shot together. In another book this might have been a distasteful dose of Hollywood schmaltz, but in Mating this is exactly right. For all their foibles, we want these two to succeed, and, moreover, after seeing them together it's believable that they'd travel half the world to try it on again. Perhaps now they realize that they're among the fallen, like the rest of us. Perhaps now the relationship will work.