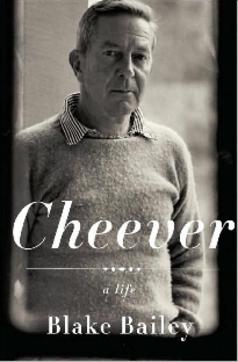

Each day leading up to the March 11 announcement of the 2009 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Steven G. Kellman discusses biography finalist Blake Bailey's Cheever: A Life (Knopf)

Each day leading up to the March 11 announcement of the 2009 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Steven G. Kellman discusses biography finalist Blake Bailey's Cheever: A Life (Knopf)

Writing fiction saved John Cheever’s life. On the strength of a collection of short stories, The Way Some People Live, that he himself considered so wretched he tried to destroy all copies of it, Cheever was mustered out of the 22nd Infantry Regiment and into writing fiction for the Army-Navy Screen Magazine in Queens. Assigned to storm Utah Beach on D-Day, most of the soldiers he had trained with eventually died in combat.

A handful of Cheever stories, including “The Swimmer,” “The Five Forty-Eight,” “The Country Husband,” “Goodbye, My Brother,” and “The Enormous Radio,” seem indelibly etched into the canon of American literature. The Stories of John Cheever won the 1979 NBCC award for fiction. Yet to his mind, the long form was the summit of literary achievement, and, not adept at constructing plots, he struggled to write novels. “I want to write short stories like I want to fuck a chicken,” he confided in a letter. Blake Bailey argues that even Cheever’s most acclaimed novels, The Wapshot Chronicle and The Wapshot Scandal, are constructed as story sequences, and he describes how “The Swimmer” succeeds precisely because its author abandoned his initial plans to make it a novel.

Bailey, whose biography of another chronicler of suburban angst, Richard Yates, A Tragic Honesty, was an NBCC finalist in 2004, offers an ancestors-to-afterlife, kitchen-sink biography of an heir to the Yankee Protestant descendancy whose kitchen was littered with empty gin bottles. A prodigious feat of research that required processing thousands of unpublished pages and coaxing testimony out of reluctant witnesses, Bailey’s exhaustive account fills more than 700 pages. While analyzing and admiring Cheever’s fiction, the book corroborates and elaborates upon a psychiatrist’s assessment of him as “a neurotic man, narcissistic, egocentric, friendless, and so deeply involved in [his] own defensive illusions that [he has] invented a manic-depressive wife.” It documents the life of a chronic alcoholic who suffered continually from what he, following the French, called cafard–the cockroach that is a metaphor for overwhelming, debilitating depression. Cheever’s own daughter, Susan, described her father as a “sexual omnivore,” and his ravenous libido, propelling him toward women, men, and masturbation, remained conflicted and at least partially, and painfully, closeted.

Bailey is attentive to his subject’s triumphs as well as his binges. “A page of good prose remains invincible,” declared Cheever in 1982, while accepting the National Medal for Literature, six weeks before his death at 70. In a journal entry written just before that ceremony, he declared: “Literature has been the salvation of the damned, literature has inspired and guided lovers, routed despair and can perhaps in this case save the world.” Literature saved Cheever from an early death in battle, but, in Bailey’s vivid portrait, it could not save him from his own tormented self.

Click here to read an excerpt from Cheever: A Life.

Click here to read Bailey on the messy research of revisiting Cheever's journals (a task made no easier by Hurricane Katrina…)