My Kill Adore Him, University of Notre Dame Press, 2009.

My Kill Adore Him, University of Notre Dame Press, 2009.

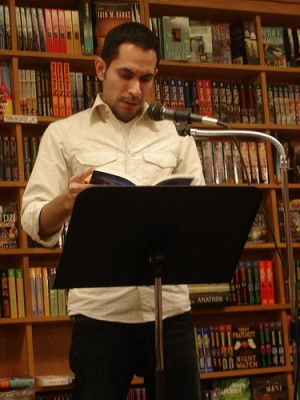

Paul Martínez Pompa is the author of Pepper Spray, a chapbook published by Momotombo Press in 2006. My Kill Adore Him, his first full-length collection, was selected for the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize in 2008.

The city of Chicago has now become the largest urban city in the U.S. with the highest number of Latinos of Mexican descent. It’s no accident that Mexican/ Chicano culture is now part of every artistic fabric of the city. You work and live in Chicago–are you a native? How have you seen the Latino literary landscape change in the Windy City in recent years?

More Latin@s actually live in suburban Chicago than in Chicago proper. I don't think many people outside of the Chicago area realize that. I am a native of suburban Chicago, not Chicago. Readers unfamiliar with Chicagoland demographics may mistake my work as speaking exclusively to urban issues when in reality I’m writing about a suburban landscape as much as an urban one. As far as the literary scene goes, it wasn’t until very recently that I felt part of a recognized literary community in Chicagoland. Even though there are more opportunities for Latin@ writers now than even just a few years ago, Latin@s have been doing their thing in defiance of the literary status quo for decades in Chicago (e.g. Ana Castillo, Carlos Cumpián, Gregorio Gómez, and of course La Sandra). Current Latino-themed reading series like Palabra Pura and Proyecto Latina and public spaces like Irasema González’s Tianguis Books have been a big help in making our work more visible, but we’ve always been here. So I suppose the main change is one of recognition.

Who are some of the important Chicago and non-Chicago influences, Latino and non-Latino, in your work?

The first significant influence was Ana Castillo. I immediately connected to the underlying anger in her work. I understood that it stemmed from a deep love and desire for truth. I was also drawn to her ability to use a more communal diction to address complex social issues. Hers was a poetics that could hold its own on the streets and in the academy. Another big influence was Kevin Young, who was a professor of mine at Indiana University. He got me thinking more intensely about the line and its importance as an entity in its own right and how each line, enjambed or not, should attempt to evoke something meaningful, not just be a passive set up for a subsequent line or image.

Despite the cultural and economic wealth associated with Chicago, your poems inhabit the working class spaces and speak out about the injustices against its day laborers, sweatshop workers, Latino youth, the homeless, etc. And by the final section of the book the tone is all-out politics and poetic manifesto. Is the distance between the haves and have-nots a palpable rage in the city?

The difference between the haves and have-nots is a stark contrast that is found just about everywhere in Chicago. It’s difficult to grow up in the area without some degree of class consciousness. As an undergrad, I transferred from a community college to the University of Chicago, a top-tier, private university. Many of my U of C peers were from wealthy and/or educated families while I was not. It was an eye-opener to see how the haves lived and where they came from. It was there that I first started writing poetry. I used it as alternative space for resistance, a space where I could examine the differences in privilege that I watched play out on and off campus, a space where I could reflect on class and race-based childhood experiences, a space where I could do and say whatever the fuck I wanted. I grew up in a neighborhood that included section 8 families, but we were within walking distance of million dollar homes inhabited by 6-figure-salary families. You see similar contrasts now in the city, where pricy, pristine condos have been erected literally across the street from dilapidated projects. When I write about class, to some extent I’m writing from memories of inferiority, shame and disempowerment, but I attempt to reconcile such feelings by placing them in their proper historical and economic contexts.

How did you negotiate preserving the fury of the tone without slipping into propaganda or preachiness?

As much as I hated my U of C experience, I learned a lot from it. Regardless of your major, you had to write like crazy there. And you couldn’t bullshit. You had to come correct with your political posturing because there was always someone who had more information than you and who was just waiting to call you out on your inconsistencies and intellectual shortcomings. It was an extremely intense place where everyone—peers as well as professors—challenged your intellect. I felt constant pressure to stay on my toes for fear of being perceived as stupid or unworthy of attending that institution. Considering where I had come from, I was way out of my element there. I quickly realized that how you said something was just as important as what you were saying. I learned to keep my craft tight because that would be the first thing under attack as a means of dismissing my political stance or, worse, dismissing my very existence. Because of the context in which I started writing, my politics became an inseparable part of my poetics and craft. They’re one and the same for me. I don’t think you should write poetry if you don’t have anything meaningful to say, if you don’t write from a politically conscious place. I don’t care if you’re writing about petunias or police brutality; you better make conscientious choices throughout the entire writing process not only out of respect for the art but also out of respect for the political positionality you’re representing.

The lessons and heartaches of growing up a Latino male open the collection, and these poems illustrate that a number of the early encounters with oppression and violence take place in the school (the boys bathroom, sex ed class, etc.). And then come the streets, which are both dangerous and wondrous. Is it because childhood and adolescence is the crossroads of conflict and curiosity that you were able to mine the poetry? What do you see as distinctly Latino about these universal stages of human development?

I see my first book as largely an interrogation of masculinity. This interrogation is no more informed by my Chicano heritage than, say, an Irish or Italian American poet is informed by his heritage. That is, it is hard to say what is distinctively Latino about my treatment of maleness because I see the same anxieties about gender and sexuality play out in so many other cultures. American sociologist Michael S. Kimmel conceived of homophobia as being more than a fear of homosexuals; homophobia stems from men’s fear of other men, from a man’s fear of being emasculated in front of men. This fear manifests itself in all sorts of neurotic and sometimes violent behavior. I find the complexity and contradictions of masculinity to be both fascinating and horrifying. How men negotiate power and disempowerment certainly plays out differently along economic and racial lines, but, ultimately, the contradictory pressures placed upon the development of male sexuality are, I think, universal. It is the manner in which men conform to, resist, or reconcile those pressures that is perhaps culturally specific. Even then, the differences are rather small.