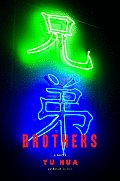

Each week Critical Mass features an exemplary review by an NBCC member. Below, in a review that originally appeared in Worlds Without Borders, Brendan Patrick Hughes considers Yu Hua’s Brothers

It is a shame that Groucho Marx is not available to appear on film in the role of Baldy Li, the ridiculous, hedonistic, almost vaudevillian main character of Brothers, Yu Hua’s epic comic novel of China’s thirty-year transformation from Maoist horror show to capitalist horror show. Only Groucho could convincingly ham his way through Baldy’s life, from his early days of humping telephone poles and hanging out underneath the town toilets to peek at women’s bottoms to his role as hymen inspector at a beauty pageant and rise to scrap metal millionaire and astronaut-tourist. Packed with gags, word games, and quotations from Mao’s “Little Red Book,” Brothers makes absurdity its hallmark—and why not? As Baldy Li and his unfortunate brother Song Gang demonstrate, to have come of age during both the Cultural Revolution and Deng Xiaoping’s market-based reforms is to have grown up absurd.

The novel begins quite literally in the toilet. Hanging by his feet over a cesspool, Baldy Li glimpses the bottom of Lin Hong, the town’s beauty, when he is pulled up suddenly by Victory Zhao, the town poet, and admonished for his unseemly behavior. Baldy Li is fatherless—his father attempted the same toilet-peeking maneuver but fell in, drowning in excrement—and thereafter Baldy Li is recognized, to his mother’s shame, as “a chip off the old block.” When his mother, Li Lan, marries Song Fanping, a school teacher and father of Song Gang, who is “a year older and a head taller” than Baldy Li, the two boys become inseparable. Much is made by both the boys and the townspeople of their brotherhood when in fact they are not technically brothers at all.

Hua’s novel has a sprawling cast—upwards of twenty by my count, and those are just the major characters—but the eponymous brothers are the focus, and Hua means for them to stand for their generation: those Chinese born after the rise of Mao and before the Cultural Revolution who lived through the economic reforms of the 1970s and 1980s, those who had the experience of both arbitrary violence and arbitrary affluence. Hua himself is a member of this generation and has said that the experience has given him “the soul of a hundred-year-old man.” That idea of arbitrariness lives at the center of Brothers. When the Cultural Revolution arrives, the boys’ father, Song Fanping, is hailed as a revolutionary leader one day and the next denounced as a scion of the landlord class because his father owned property. Unable to understand the revolutionary fervor run amok, Baldy Li and Song Gang join in instead, wandering “through town like a couple of stray dogs. They followed one brigade after another, repeatedly yelling ‘Long live!’ after one and ‘Take down!’ after another. They shouted until their tongues were parched and their throats were raw and swollen.” It seems like great fun and excitement until the mob turns on Song Fanping and beats him to death.

During the Cultural Revolution, a person could, like Song Fanping, be denounced just on the word of his or her neighbors, and so language became a very powerful weapon. It could be used to settle scores or inflict senseless violence under the guise of enforcing Maoist ideology. Hua delights in wordplay throughout Brothers, probing the gap between what is said and what is meant, between professed motives and underlying ones. A recurring gag is Baldy Li’s exploitation of his “brotherhood” with Song Gang in order to get what he wants. In one scene, after Song Gang has won over Lin Hong, Baldy Li collapses in tears and then tries to coerce Song Gang into leaving her. “Song Gang rushed at Baldy Li saying, ‘If it were you, what would you do?’ ‘If it were me,’ Baldy Li shouted back, ‘I would slaughter you!’ Song Gang looked at Baldy Li in surprise and, pointing at himself, said, ‘But I’m your brother!’ ‘Even as a brother, I would still slaughter you,’ Baldy Li immediately retorted.” It’s enough to wrangle Song Gang into giving him one last shot at getting the girl, but the threat is prophetic.

Song Gang takes care of Baldy Li after their mother dies and selflessly renounces Lin Hong out of concern for his brother, but their paths soon diverge. While Baldy Li is entrepreneurial and self-absorbed, his brother is reserved, even diffident, and always puts family first. Song Gang aspires to be a writer but gives up after a colleague criticizes one of his stories. Baldy Li, on the other hand, is consumed by an impulse to build and acquire. After Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, he starts a scrap business and eventually becomes a millionaire. Song Gang, on the other hand, drifts through a life of poverty, contracting a lung infection and working as a traveling salesman of breast enhancing cream (in another of Hua’s comic flourishes, Song Gang gets breast implants in order to demonstrate the product and improve sales). When he returns home and finds that Baldy Li has taken up with his wife, Song Gang commits suicide by throwing himself in front of a train. At the end of the novel, Baldy Li, who has paid $20 million to be launched into orbit in a Russian rocket, prepares to take his brother’s ashes into space, and the reader starts to sense the creeping entropy. The book doesn’t so much end as spin out to the sound of crazed, raucous laughter.

It is interesting to compare Brothers to Yiyun Li’s novel The Vagrants, which covers some of the same historical ground. Both authors are Chinese-born (Li is twelve years younger than Hua), but Li’s novel is relentlessly grim and serious, a sharp contrast to Brothers, which despite its spasms of horrific violence hardly goes a page without Baldy Li hatching a new harebrained scheme. Both are powerful in their own ways, but the dissolute grip of Brothers is harder to shake and its dark comedy contains a more powerful critique of post-Cultural Revolution Chinese culture. In the novel’s closing chapters, the unnamed narrator muses on Baldy Li’s and Song Gang’s disparate lives and fates: “Thus was life: Someone who was walking toward death might linger over the setting sun’s glorious rays, while two others who were hedonistically pursuing pleasure might be completely oblivious to the beauty of the sunset.” In the China of Brothers, it’s the acquisitive pleasure-seeker, not the wandering beauty-lover, who survives.