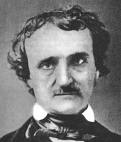

On the occasion of the anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s death this week, NBCC member Allen Barra sent along the following thoughts on the writer’s fading star.

Someone – I’ve never been able to find out who, though I’d bet it was either G.K. Chesterton or Cyril Connelly – once wrote that a favorite Victorian writer of his youth had entered “the twilight realm of the praised but unread.” It’s hard to tell when a writer is slipping into that realm; it’s even harder to tell when they’ve already been there for a couple of decades.

As we approach the 160th anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s death on October 7 – and it seems more fitting to talk about Poe on the anniversary of his death than of his birth – it might be time for a revaluation of sorts. In How To Read and Why, Harold Bloom commented that Edgar Allan Poe’s poems and stories, “despite their permanent worldwide popularity, are atrociously written … and benefit by translation, even into English.” Ouch! Bloom is right about Poe’s stories and poems being atrociously written; they are often prolix and florid and most of them seem to have been written in a tone of near hysteria – though, considering most of Poe’s subject matter, one could argue that the tone was appropriate.

Bloom may be wrong about Poe’s permanence. Though he is still widely praised by most critics and his work still included in many anthologies, Poe may be fading into that twilight realm, indeed as he was as early as 1950 in Ray Bradbury’s story, “The Exiles,” where he is languishing on Mars with Shakespeare and Dickens, among others, as people back on Earth burn their books.

Shakespeare and Dickens are still pretty solid, but Poe’s stock is slipping. His name is as much with us as ever – the Edgars are awarded annually to writers of the best mystery stories and the American celebration of Halloween owes more to Poe than Christmas does to Dickens. One of his poems even inspired the nickname of the National Football League franchise in the city of Baltimore, where Poe died under mysterious circumstances 160 years ago this week. His name is still instantly recognized; a few years ago he popped up on an episode of “Sabrina The Teenage Witch,” where his ghost has ceased writing macabre tales and taken up inspirational greeting cards (“where the real money is”). Earlier this year Harper published On A Raven’s Wing: New Stories in Honor of Edgar Allan Poe with fictional homage by writers such as Mary Higgins Clark and Rupert Holmes.

Yet the readership of Poe the writer seems to be shrinking. For a couple of decades, the 1938 edition of The Complete Tales and Poems (which included a few of Poe’s critical essays), with an introduction by Hervey Allen, was the standard Poe at 1,028 pages. (It was reprinted in 1965 and sold for $3.95, the edition my mother bought for me on my birthday.) In 1971 Modern Library replaced that with Selected Poetry and Prose (also with the critical essays and 23 pages of notes by T.O. Mabbott), which checked in at 428 pages. There was a 1992 reprint of The Complete Tales and Poems, but most editions since then have been far slimmer: in 2006 Modern Library issued a 160-page edition of the Inspector Dupin tales with an introduction by Matthew Pearl, and the next year saw a new edition of Poe’s novella, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

You can find a complete Poe these days, but who reads it all? Most Poe collections of the last twenty or so years include just a handful of his best known stories and poems, seldom more than 200 pages worth. The recent In the Shadow of The Master: Classic Tales by Edgar Allan Poe (William Morrow) paired seventeen Poe stories with commentary from modern writers (Sample: Stephen King on “The Genius of the Tell-Tale Heart”).

The size of Poe’s oeuvre that is still read grows smaller every year, and the chorus of those who praise him becomes more marginalized. Outside of mystery and hero writers, it’s hard to find anyone who still thinks Poe is a genius. Nine years into the 21st century, he has become what Peter Ackroyd in his 205-page biography, Poe: A Life Cut Short (published this past January to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Poe’s birth), calls “the image of the poet maudit, the blasted soul, the wanderer. His fate was heavy, his life all but unsupportable.” Okay, the image is still with us, but what is Poe’s literary standing?

For the first 75 years after his death, he was lionized by Europeans who couldn’t understand why we couldn’t understand him as well as they did. Tennyson thought him to be “the most original genius that America has produced.” Nietzsche, Kafka, Yeats, and Joyce all claimed to draw inspiration from him, and, as we all know, the French, most famously Baudelaire, regarded him as the greatest American export till Jerry Lewis. Maybe Bloom was right about Poe benefiting from translation.

But is that really true? In his 1996 study of Baudelaire, Marcel A. Ruff wrote that “many commentators have attributed considerable importance to the influence of Poe on Baudelaire’s thought and work, basing their opinion on the poet’s enthusiasm, and the tenacity with which he carried out the vast undertaking of translating Poe’s work into French. However, we must interpret Baudelaire’s fascination with prudence. It is true that we can call upon many facts and documents concerning Poe. Five volumes of translations are in existence, representing fifteen years of more or less sustained effort in the course of Baudelaire’s life. His admiration, formulated in no uncertain terms, was stated in the various commentaries that accompanied these translations, as well as in his correspondence. In the light of such evidence, some critics have posited a genuine infatuation on Baudelaire’s part and have affirmed, as did Paul Valery, that Poe’s conception of aesthetics ‘was the principal factor in influencing Baudelaire’s art and ideas.’ ”

Such assertions, thinks Ruff, “call for a thorough examination of this question.”

Referring to the work of an American scholar, W.T. Bandy, Ruff asserted that “Baudelaire did not become acquainted with Poe’s work until 1852. Before this date, he had not read either his poems or his theoretic treatises. He had become familiar with these works only that year, after the publication of his first important article, ‘Edgar Poe, sa vie et ses ouvrages.’ This article was, for the most part, simply a translation of two American articles.”

Poe’s influence, then, on Baudelaire’s later work, including Fleurs du Mal (1857), concludes Ruff, “would be disquieting only if Poe had actually exercised on Baudelaire the cardinal influence which ahs been attributed to him by the critics…. Baudelaire was profoundly by this man, whose unfortunate fate struck him as resembling his own.” Poe’s real influence on Baudelaire was that it “confirmed him in the certainty of his genius, and the knowledge of his destiny.”

It may well be that much of what we thought was Poe’s influence was an error in translation – or, in some cases, in interpretation. One of the more interesting revelations of Brad Gooch’s recent biography of Flannery O’Connor, Flannery: A Life, regards Poe’s actual influence on O’Connor’s work. Gooch quotes Elizabeth Hardwick, her friend and contemporary, on the subject of Poe. “We didn’t have a lot of books in my house, but we did have the complete Poe,” said Hardwick of her childhood in Kentucky. “I bet they [the O’Connors] had the same edition. I remember sitting on the front porch in Lexington and reading ‘Murder in the Rue Morgue.’ I’ve often looked back and thought, ‘How did that happen?’ You have nothing to read when you’re twelve and you’re reading Poe.”

Indeed, the O’Connors did have the same ten-volume “commemorative” edition of Poe on the family bookshelf. “She enjoyed,” Gooch writes, “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, a short lyric novel about a stowaway on a whaling ship whose survivors resorted to cannibalism. But her favorite was the volume eight, the Humorous Tales, including ‘The Spectacles,’ ‘The Man That Was Used Up,’ and ‘The System of Dr. Tarr’ and ‘Professor Fether.’ She later recalled, ‘These were mighty humorous – one about a young man who was too vain to wear his glasses and consequently married his grandmother by accident; another about a fine figure of a man who in his room removed wooden arms, wooden legs, hairpiece, artificial teeth, voice box, etc. etc.; another about the inmates of a lunatic asylum who take over the establishment and run it to suit themselves.’ ” (In the same letter from O’Connor quoted above, she added: “I’m sure he wrote them all while drunk, too.”)

If someone has asked O’Connor, I’m certain she would have included “Some Words with a Mummy,” a cynical and satirical story about a mummy who, when revived by archeologists, lectures a group of them about the superiority of ancient Egyptian life over the marvels of the early nineteenth century West. The story, along with the others O’Connor named, was very popular among high school and college English teachers when I was growing up in Alabama in the 1960s.

So Poe did in fact have a profound influence on the writer who many consider the ultimate writer in the Southern Gothic tradition – though not in the sense that many have believed. What O’Connor liked best was the relative handful of sardonically humorous stories that we no longer read today.

So what are we left with as a pure, unadulterated influence? Stephen King?

If Poe is stripped of much of the support that Baudelaire and Flannery O’Connor lent to his reputation, who then, more than a century and a half after his death, still lines up behind him? He’ll always be an influence on the mystery writers; they wouldn’t exist without him. He didn’t invent gothic horror, but he did give it some gravitas and a veneer of literary authenticity. But can a serious case really be made for Poe by claiming that H.P. Lovecraft and Stephen King found inspiration in his work?

Mystery and gothic horror, though, are still genres, no matter how much their fans try to inflate them with significance. It’s true that great writers who transcended genres were inspired by Poe, but their admiration does not lift him to their level. We accept their praise for Poe as genuine, but less and less are we compelled to read him.