Visitors to Critical Mass will recall that in the fall, we canvassed the membership (as well as former winners and nominees) about which books best captured the realities of American politics. This time around, we have cast the net even wider. Our question: which work in translation has had the most effect on your reading and writing?

We heard from nearly eighty people, all of whom deserve our gratitude for their thoughtful responses. Not surprisingly, there was a wide range—geographic, stylistic, chronological—among the selections. Still, a few titles or authors did get multiple nods from the crowd. Scott Esposito, the proprietor of Quarterly Conversation, turned cartwheels over Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus.  “The book embodies so many currents in art and politics,” he noted. “Some of them are timeless, like the Faust legend and the question of morality in art, and some of them are historical but still remain vital (including, of course, that one big question that Jonathan Littell has just demonstrated the continuing resonance of).”

“The book embodies so many currents in art and politics,” he noted. “Some of them are timeless, like the Faust legend and the question of morality in art, and some of them are historical but still remain vital (including, of course, that one big question that Jonathan Littell has just demonstrated the continuing resonance of).”

There was a similar response from David Carr, with a couple of caveats. He called the novel “the second most influential translation in my life. I read it at 17, before college, and used it later in advanced undergraduate German courses, and then again on my undergraduate comprehensive examinations, when I was asked to discuss the relationship between sickness and creativity. It was useful, if not moving.” Meanwhile, Honor Moore, a 2008 NBCC nominee in memoir, gave high marks to another work by the same author: “John Woods’ translation turns The Magic Mountain into a masterpiece of wit and drollery—presumably returning the comic subtlety [that was] there in the original. What a great achievement.”

Also in heavy rotation: Albert Camus. For Balakian winner Steve Kellman, the French novelist’s prose was a kind of gateway drug. “If a good review entices you to read the book,” says Kellman, “a powerful translation propels you to the source. It was on first looking into Albert Camus’s The Stranger, The Plague, and The Fall (grâce à Stuart Gilbert and Justin O’Brien) that I determined to learn French. Camus’s style is spare and simple—a Gallic Hemingway, if Hemingway had done his writing, not just his drinking, in French. It was ideal for a novice étudiant, and it was on from there to Molière, Baudelaire, and Proust. But L’Etranger, La Peste, and La Chute still stun me, like a pistol shot on a sunny beach.”

Chelsey Philpot seconded that emotion. She read The Stranger “for the first time in high school and was completely undone by the descriptions and the haunting imagery.” Shaun Manning, too, was bitten by the Camus bug in high school. At that point, the novels appealed to his “sense of wonder and desire to see Weighty Meaning expressed through unconventional storytelling. While my tastes have evolved quite a bit since then, I still enjoy these books.” Wendy Smith made it a threesome, calling The Rebel “the most influential work I have read in translation.”

Then there was that Everest of French letters, whose vertiginous heights and winding descents have bested many a translator: Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Daniel Dyer saw the multi-volume monster as an absolute summit. “I am in my sixties,” he said, “and recovering from prostate cancer surgery.  I decided it was, well… time. I read 100 pages a day, every day, until I finished the volumes. I think these are the greatest literary works ever written by a human being. I’ve not read everything, of course—not even everything that’s celebrated. But I cannot imagine anything better.”

I decided it was, well… time. I read 100 pages a day, every day, until I finished the volumes. I think these are the greatest literary works ever written by a human being. I’ve not read everything, of course—not even everything that’s celebrated. But I cannot imagine anything better.”

Michael Sims agreed, praising the magic-lantern quality of Proust’s imagery and his prodigal, preening cast of characters. “Most of the time,” he concedes, “I find the characters maddening—petty, self-absorbed, posturing, judgmental, although of course often hilarious and sometimes tragic. But I don’t read for the characters. I read, I think, for the cinematography. Has there ever been such loving attention to the sensualities of the moment? ‘It was on the Méséglise way that I first noticed the round shadow that apple trees make on the sunny earth and those silks of impalpable gold which the sunset weaves obliquely under the leaves, and which I saw my father interrupt with his stick without deflecting them.’ I quote this almost random selection (from the Lydia Davis translation) as an example of the kind of snapshot imagery that Proust seems to casually exhale without thinking: the glimpse immortalized. So generous is his encyclopedic curiosity, so Olympian his empathy, that even passing shadows have personality.”

Still a third member, Ellen Pall, tipped her hat to Proust for enriching her “understanding of people and the nature of human experience.” And Ted Gioia put in a special word for C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation, which many readers have now abandoned for the more streamlined versions produced by Terence Kilmartin, Lydia Davis, and various other masochists. “In fact,” suggests Gioia, “you can tell that [Moncrieff] enjoys scaling these grand periods as much as the humble reader.”

Another favorite was Milan Kundera. Dexter Filkins, who won the 2008 NBCC award in general nonfiction, singled out the translator of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. As Filkins saw it, Michael Henry Heim had attained the Holy Grail of every translator: invisibility. “I guess the best measure of a translation,” he wrote, “as with any work of art, is that you don’t notice the work that went into it. It just is. So I had to think about this question a little. What translated work was so good that I never noticed that it was translated? That would be The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Kundera, who writes in Czech and in French, is concerned about the missed connections between human beings, the trap that our world has become. His prose comes across so clearly in English that it’s impossible to imagine it written in any other language.” Elizabeth Benedict concurred, ranking the novel with Anna Karenina for their “ambition, depth, breadth, and the sheer pleasure they give.”

Jason Erik Lundberg opted for a different novel, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. “It combines the fascinating narrative of Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia with amazing philosophical erudition and trenchant observation,” he wrote, “and it does this using elements of the fantastic. The novel is also very structured (as are many of Kundera’s texts), so that it feels like a symphony built of disparate parts, but held together by common themes and experiences.” Two other members tossed bouquets at Kundera. Peter D. Kramer praised his ruminations about translation in Testaments Betrayed, and Leigh Rastivo Nolan drew attention to the emotional chiaroscuro in all of his novels: “Kundera’s works have taught me that stories can be, and should be, both lively and moody at once.”

Finally, a deviation from Western Europe, and from a reading list that might have been drawn up at a NATO summit: Haruki Murakami. His Wind-Up Bird Chronicle elicited a couple of eloquent endorsements.  Said Christine Thomas: “Reading this surreal indictment of the cost of keeping Japan’s wartime atrocities secret from its people awakened me from a reading slumber and injected life into my own fiction writing, at the time being conducted in England far from my home in Hawaii.” Added Diane Raabe (who put in a plug for Alfred Birnbaum’s elegant translation): “The angst-turned-calm of the Japanese protagonist was a journey that was easy to share…. Reading this book made me look at things in such a fresh way that my personality was somehow lighter.” [Editor’s note: Jay Rubin should be credited with the translation—see Comments.]

Said Christine Thomas: “Reading this surreal indictment of the cost of keeping Japan’s wartime atrocities secret from its people awakened me from a reading slumber and injected life into my own fiction writing, at the time being conducted in England far from my home in Hawaii.” Added Diane Raabe (who put in a plug for Alfred Birnbaum’s elegant translation): “The angst-turned-calm of the Japanese protagonist was a journey that was easy to share…. Reading this book made me look at things in such a fresh way that my personality was somehow lighter.” [Editor’s note: Jay Rubin should be credited with the translation—see Comments.]

All of the titles mentioned so far are modern works. But there was also plenty of enthusiasm for classic texts. Balakian winner George Scialabba gave a clap on the back to a certain Roman pottymouth: “After a few minutes’ thought (though of course this question deserves hours), what comes to mind is Carl Sesar’s translation of Selected Poems of Catullus. It’s long out of print, and I’ve never seen it referred to, so it’s partly a matter of honoring an underdog. But Sesar takes the most wonderful liberties of tone, and the result is a collection of hilarious, smutty, bitchy, and touching verses that left me gaping. Whether it’s precisely Catullus, I have no idea—I don’t read Latin nearly well enough. But it manages a small miracle: an entirely fresh, contemporary voice that never once made me wince and think, ‘Oh well, Catullus probably wouldn’t have said it like that.’”

Switching geographical gears for a moment, Andy Solomon praised an even earlier production, “the Taoist classic of roughly four centuries B.C., the Chuang-tzu (in the Burton Watson translation), an amazing blend of human understanding and metaphysical insight.” And Michael Antman spoke up on behalf of R.H. Blyth’s four-volume survey, Haiku. Said Antman: “[It] opened to me the world of Japanese literature when I was in my early twenties, and helped me to understand the advantages, and limits, of concision. The books themselves, with their textured linen covers and plates featuring the sublime paintings and calligraphy of Hakuin, Issa, and other masters, are exemplars of the art of book design.”

Moving forward in time, David Tereshchuk of Media Beat spoke up on behalf of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf. Here, he said, was an modern English rendering that made this “often unwieldy classic” genuinely new. Mary Jo Bang, a 2007 NBCC nominee in poetry, felt the same way about Charles S. Singleton’s prose translation of the Inferno. “I felt timid years ago when I set out to read the Inferno for the first time,” she confessed. “Singleton’s elegant prose made it possible for me to read and enjoy the poem; later I was able to use that translation as a standard against which to read other translations. Singleton’s version allowed me to see the liberties other translators were taking, and to appreciate the effect of departure from the strictly literal. To see how nuanced shifts were possible with the simple substitution of a word. I still have complete faith in it and compare all other translations to it.”

Colin Foote Burch chose Blaise Pascal’s Pensées, and quoted a couple of aphoristic gems that addressed the writer’s task in particular: “The last thing one discovers in writing a book is what to put first.” Norman Rush gravitated to a very different monument of French literature, and gave some delightful background about his introduction to the mad, mad world of imaginative prose. “My father was an armchair libertine,” Rush recounted. “In his (as he thought) secure collection of racy books (The Sexual Life of Savages, Erskine Caldwell, Jack Woodford, and everything from the Fanfrolico Press ), I found an illustrated 19th-century translation of Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel. I was only a boy, and I was astonished. I noted well that apparently one could write anything.” He also tipped his hat to the John Florio’s 1603 translation of Montaigne, calling it “a model of discursive and literary beauty combined that knocked my socks off.”

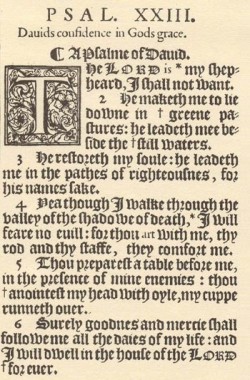

There were also a fair number of votes for sacred texts and philosophical landmarks. Jim Gibbons put in his for the King James Bible. So did non-believer Jay Rogoff: “Atheist though I am, I can’t escape the likelihood that of all translated books, the Bible has had the greatest impact on my work, especially in the King James translation.  Lovers of poetry in English would find their experience of much pre-20th-century work (and even much modern work) diminished without some familiarity with the Old and New Testaments, not just as a collection of stories and nostrums, but as a linguistic force that has infected our literature for four centuries.”

Lovers of poetry in English would find their experience of much pre-20th-century work (and even much modern work) diminished without some familiarity with the Old and New Testaments, not just as a collection of stories and nostrums, but as a linguistic force that has infected our literature for four centuries.”

David Haglund seemed seriously tempted by the Book of Mormon, then peeled off to join Gibbons and Rogoff: “Since I no longer believe Joseph Smith translated that text—from the original ‘reformed Egyptian,’ if you’re curious, using first an angelic breastplate-and-spectacle contraption and, later, a seer stone—I’ll say the King James Bible, which might be the more accurate answer at this point anyway. Like the Book of Mormon, the Bible was scripture for me until age nineteen. Unlike the Book of Mormon, it remained a literary touchstone beyond that age.”

Then there were those philosophical works that sprang directly from a dialogue—sometimes an acrimonious one—with Christianity. Said Michael Lindgren: “Forced to choose, I would probably go with Søren Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript, which shaped my thinking about the paradoxes of Christianity at an early and impressionable age. Kierkegaard says that being a true Christian is impossible, and that God is fundamentally unknowable. Yet in saying so, he somehow makes the impossibility and unknowability seem essential, mysterious, and worth striving towards. I have the volume somewhere—a thick, mustard-colored slab of paper, bought used at the college bookstore—but cannot offhand remember the translator, who surely deserves better.”

Robert Archambeau, meanwhile, gave the palm to Kant’s Critique of Judgment. It was, he explained, “important to me in all kinds of ways—not least as a critic. Whether you agree with him or not, Kant makes you clarify just what it is that you’re doing when you make a judgment about what you’ve read.”

Dante and Catullus notwithstanding, it may appear so far that poetry got short shrift from our respondents. Not so! Nicky Beer had some understandable difficulty whittling down her list, so she stuck with the great troika of modern Polish poetry: Zbigniew Herbert, Czeslaw Milosz, and Wislawa Szymborska. “The way that their witty, intellectual, compassionate poetry stood as a rebuke to the totalitarian regimes under which they’d lived was something I’d never encountered before: literature that was explicitly subversive by its humane example, rather than because of any kind of shrill dogma or doctrine,” she wrote.

Frank Freeman and Jim Schley also listed Milosz as a formative poet. And Todd Shy of the Raleigh News and Observer zoomed in on one particular volume, A Treatise on Poetry (2001), which Milosz translated with longtime collaborator Robert Hass. “A ‘Wasteland’-length meditation on Poland before and after the two world wars,” he wrote, “Milosz’s poem manages to grieve and affirm and empathize with a haunted authority. An homage to Krakow café life here, a quick biography of Conrad there, Holocaust crimes, soldiers, poets, an image of two lovers beneath an overcoat in the rain—the smoke of the half-century clears, and the fragile world starts over. How can this seem so redemptive?”

Two Latin American poets (well, one of them an Italian transplant to Argentina who wrote in Spanish) also got the nod. Said David Carr: “The most important translation in my life is W. S. Merwin’s version of Voices, by Antonio Porchia. The poems have never left me, and I would want them to be the last things I read in my life, if I can control that. Unfortunately it is more likely to be some crime book, or a Western.”

Grace Schulman selected a book she not only admired but also translated: Pablo Antonio Cuadra’s Songs of Cifar and the Sweet Sea. “Cuadra [was] a Nicaraguan who died in the 1980s,” she wrote, “and I had a co-translator, Ann McCarthy de Zavala. I’m fascinated by the narrative of this long poem. Cifar is a sailor on Lake Nicaragua, which contains, oddly, sharks and shad, hence ‘sweet sea.’ Cuadra creates allusions to the characters and places in Homer’s Iliad, notably Helen, Odysseus, Calypso, Penelope, while at the same time telling a story about Nicaraguan fishermen.”

Other poets elicited more brief but no less heartfelt testimonials. Sara Paretsky wrote that “many books in translation have affected me profoundly, but the one I keep going back to is [Anna] Akhmatova’s poem, ‘Requiem.’” Jim Gibbons praised “the Rilke translations of Stephen Mitchell and William H. Gass—from the more than twenty versions of Rilke in English, the only translations I can bear to read.” And Ben Mirov singled out Kenneth Rexroth’s versions of Pierre Reverdy: “There are many fine translations of Reverdy, but Rexroth’s is the best because it captures the lapidary qualities of Reverdy’s imagery and the miraculous nature of his poems.”

Other poets elicited more brief but no less heartfelt testimonials. Sara Paretsky wrote that “many books in translation have affected me profoundly, but the one I keep going back to is [Anna] Akhmatova’s poem, ‘Requiem.’” Jim Gibbons praised “the Rilke translations of Stephen Mitchell and William H. Gass—from the more than twenty versions of Rilke in English, the only translations I can bear to read.” And Ben Mirov singled out Kenneth Rexroth’s versions of Pierre Reverdy: “There are many fine translations of Reverdy, but Rexroth’s is the best because it captures the lapidary qualities of Reverdy’s imagery and the miraculous nature of his poems.”

Believe it or not, there are many responses not enumerated above, and we will be featuring quite a few of them in freestanding “Long Tail” posts throughout the rest of May. But it seemed appropriate to end with a couple of outliers—favorite works in translation with a certain left-field quality. (We’ll go ahead and grant the subjective nature of this category: one reader’s fish is another reader’s poisson.) To a large degree, Tim Gebhart credited The SFWA European Hall of Fame: Sixteen Contemporary Masterpieces of Science Fiction from the Continent with ushering him into the world of non-English prose: it was “the first time I knowingly, so to speak, read literature in translation. I was hooked. Since then, I’ve read more than three dozen translated works and have a subscription for Open Letter books.” (Three cheers!)

Meanwhile, Lev Grossman swam against the current in much of the Anglophone world to praise Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones. “Much maligned, most memorably in the New York Times (‘an odious stunt’), but this (admittedly overlong) book is a real work of force and intelligence, a monumental, pitiless study in the psychological degradation killers inflict on themselves. Reminds me—and I needed to be reminded—that there’s life left in the novel in French.” And, presumably, elsewhere.