Visitors to Critical Mass will recall that we launched a new enterprise called “NBCC Good Reads” last fall. We are now rolling out a slightly tweaked version of the same thing, which we have rechristened “NBCC Reads.”

Like its predecessor, NBCC Reads will allow us to draw on the bookish expertise of our membership, along with former NBCC winners and nominees. Three times a year, we will pose a question to this group. The results will be posted here at Critical Mass. We will no longer tabulate votes or rank the titles under discussion. Instead, we will simply give an idea of trends, authors, or particular titles that seem to be tickling the collective fancy. We will also post specific responses as “Long Tail” entries on the blog, and welcome further conversation in the comment threads.

Now for the latest question, which seemed especially suited to the exhausting home stretch of the current election cycle. Which work of fiction, nonfiction, or poetry best captures the realities of American political culture?

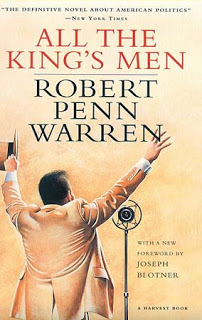

We got responses from nearly 70 people, all of whom deserve our heartfelt thanks. They gave the nod to a wide range of books, some celebrated, some obscure. There were, however, a few titles or authors that got multiple endorsements. “I predict you’ll be overwhelmed by nominations of All the King’s Men,” wrote Mike Fischer, and he was correct. While acknowledging Robert Penn Warren’s work as “a fantastic novel,” he did issue a caveat, arguing that “the colorful world of Huey Long bears little relation to the much more systemic, impersonal, and fundamentally undemocratic corporatist interests that now largely rule our country.” Meanwhile, other members were less qualified in their praise. “It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read about anything,” wrote Liz Bennett, “including politics.” John McFarland concurred, and so did Franklin Freeman: “It’s all there, the idealism and the corruption, the loyalties and betrayals, in love and politics and journalism—and an assassination to end it all.”

We got responses from nearly 70 people, all of whom deserve our heartfelt thanks. They gave the nod to a wide range of books, some celebrated, some obscure. There were, however, a few titles or authors that got multiple endorsements. “I predict you’ll be overwhelmed by nominations of All the King’s Men,” wrote Mike Fischer, and he was correct. While acknowledging Robert Penn Warren’s work as “a fantastic novel,” he did issue a caveat, arguing that “the colorful world of Huey Long bears little relation to the much more systemic, impersonal, and fundamentally undemocratic corporatist interests that now largely rule our country.” Meanwhile, other members were less qualified in their praise. “It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read about anything,” wrote Liz Bennett, “including politics.” John McFarland concurred, and so did Franklin Freeman: “It’s all there, the idealism and the corruption, the loyalties and betrayals, in love and politics and journalism—and an assassination to end it all.”

From this Dixie-fried masterpiece, it was just a lateral leap to Huey Long by T. Harry Williams. Said Mary Ann Gwinn, Book Editor of the Seattle Times: “It’s not just one of the best biographies I’ve ever read, it’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. Williams gets completely under the skin of the Louisiana populist whose life inspired Robert Penn Warren’s novel. [The book], published in 1970, was also the genesis of one of the great political music albums, Randy Newman’s Good Old Boys (1974). Newman recorded ‘Every Man a King,’ a campaign song Long wrote himself. Also on Good Old Boys is ‘Kingfish,’ a tribute to Long with a refrain that goes like this: ‘I’m a cracker, you are too, gonna take good care of you.’ Now, that’s political.”

Another political biography also earned a pair of plaudits: Mike Royko’s Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. “Frequently and somewhat painfully imitated but never equaled,” wrote Chris Barsanti, “Royko’s sardonic but thoroughly sincere portrait of Mayor Richard Daley is quite simply the most illuminating work on American urban politics that I’ve ever read. Royko slices past all the usual ‘City of Big Shoulders’ cliches and captures the essence of Chicago’s unique brand of city politics, not to mention the prickly and dour South Side Nixonian who pulled all its strings.” Mark Athitakis was no less enthusiastic. “The book is not only a provocative portrait of Chicago’s imperious longtime mayor, Richard J. Daley,” he noted. It is also “an exemplar of the kind of fearless civic journalism that questions power, in a time when we’re overflowing with punditry and nitpicking and badly hurting for the relevant facts.”

Still on the biographical front, Wendy Smith opted for the most recent installment of Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson: “All three volumes (so far) of Caro’s Johnson biography are brilliant, but nothing tops this volume as a study of political life in America: what it takes to get bills passed, how someone like LBJ accumulated power, etc. The sheer volume of detail is amazing, and Johnson emerges as one of the most titanic, fascinating figures ever in American history. When, oh when, will we get the next volume?” (Until Caro cranks out the concluding salvo, addicts can always satisfy their LBJ jones with Billy Lee Brammer’s The Gay Place. “Brammer was a press secretary for Lyndon B. Johnson,” wrote Michael Upchurch, “and this Texas-set trilogy—about a crude, larger-than-life, Johnson-like Texas governor surrounded by legislators, favor seekers, members of the press, and the occasional movie star—is smart, funny, and so beautifully written it takes your breath away.”)

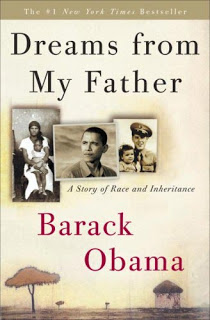

While you’re waiting, you might be advised to check out both of Barack Obama’s autobiographical productions. Richard Tayson called The Audacity of Hope “the most important book that I have read this year. The reasons: not only does Obama give a succinct history of the post-WWII shaping of the American political landscape (along with a tempered description of what is wrong with American political culture)—he also gives examples of how he has worked in government to bridge seemingly intractable differences.” The Democratic candidate’s earlier book also won its share of praise. Susan Settlemeyre Williams “found it a very honest and revealing work, more credible than most political autobiographies/memoirs, perhaps because it was written well before Obama became involved in politics.” There was a similar sentiment from 2007 NBCC winner Alex Ross. Dreams From My Father made him “feel, for a little while at least, quite a bit better. Like many people who have picked the book up in recent months, I was startled by the beauty and sharpness of the writing. I got a strong and rather wistful feeling at the end: Obama’s chief ambition at the time was not to become president of the United States, but to make his way as an author of books.”

While you’re waiting, you might be advised to check out both of Barack Obama’s autobiographical productions. Richard Tayson called The Audacity of Hope “the most important book that I have read this year. The reasons: not only does Obama give a succinct history of the post-WWII shaping of the American political landscape (along with a tempered description of what is wrong with American political culture)—he also gives examples of how he has worked in government to bridge seemingly intractable differences.” The Democratic candidate’s earlier book also won its share of praise. Susan Settlemeyre Williams “found it a very honest and revealing work, more credible than most political autobiographies/memoirs, perhaps because it was written well before Obama became involved in politics.” There was a similar sentiment from 2007 NBCC winner Alex Ross. Dreams From My Father made him “feel, for a little while at least, quite a bit better. Like many people who have picked the book up in recent months, I was startled by the beauty and sharpness of the writing. I got a strong and rather wistful feeling at the end: Obama’s chief ambition at the time was not to become president of the United States, but to make his way as an author of books.”

Richard Hofstadter, a less sanguine observer of the American political terrain, was cited by several members. Sara Paretsky toyed with nominating him before casting her vote elsewhere (more on that later). Tim Brown delivered a twofer, praising both Anti-Intellectualism in American Life and The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. “Published in 1963 and 1965, respectively, these books should be read together to understand the present political moment and two of the darker currents running through American history and politics,” he declared. “Anti-Intellectualism discusses how ‘elite’ opinion has often been used as a foil for opportunistic politicians and preachers, who emphasize an opposing sense of ‘morality,’ to manipulate the populace…. The Paranoid Style, which contains Hofstadter’s classic Harper’s essay, traces Americans’ irrational tendency to blame shadowy forces for conspiring to undermine traditional American values.” Mark Ciabattari also praised the latter title for its (unfortunate) relevance: “The 21st century has brought us fear of terrorism and an intense scrutiny of ‘patriotism’ that once again sets up a conflict between cosmopolitan ‘elites’ and small-town ‘Joe the Plumbers.’”

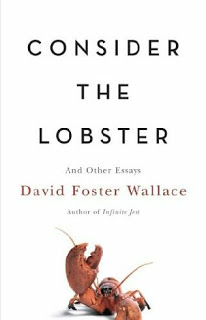

Hofstadter wasn’t the only essayist to win high marks for prescience. Two members singled out the late David Foster Wallace, whose capacity for unflinching, synapse-blowing self-examination was noted by Lia Purpura: “If only we found this kind of internal accountability in our leaders, this sense of personal complicity in the systems by which we live, this level of scrutiny of ‘evaluative filters’ we assent to! Wallace’s own participation in the outsourcing of decision-making—and fear of our desire for it, for the forms of ease and comfort it offers—speaks not only to the tyrannies of aesthetic taste-making but to more dangerous scenarios by which a citizenry gives up on individual decision-making.” Said Lev Grossman: “It’s moving (in several different ways) to reread ‘Up Simba,’ an essay in David Foster Wallace’s Consider the Lobster, in which—in a pairing that now seems incomprehensible—Rolling Stone sent Wallace to shadow McCain on the campaign trail in 2000. Wallace directs his x-ray-vision-like critical faculties at McCain’s actual and media personas, and finds the two difficult to disentangle.”

Hofstadter wasn’t the only essayist to win high marks for prescience. Two members singled out the late David Foster Wallace, whose capacity for unflinching, synapse-blowing self-examination was noted by Lia Purpura: “If only we found this kind of internal accountability in our leaders, this sense of personal complicity in the systems by which we live, this level of scrutiny of ‘evaluative filters’ we assent to! Wallace’s own participation in the outsourcing of decision-making—and fear of our desire for it, for the forms of ease and comfort it offers—speaks not only to the tyrannies of aesthetic taste-making but to more dangerous scenarios by which a citizenry gives up on individual decision-making.” Said Lev Grossman: “It’s moving (in several different ways) to reread ‘Up Simba,’ an essay in David Foster Wallace’s Consider the Lobster, in which—in a pairing that now seems incomprehensible—Rolling Stone sent Wallace to shadow McCain on the campaign trail in 2000. Wallace directs his x-ray-vision-like critical faculties at McCain’s actual and media personas, and finds the two difficult to disentangle.”

A less footnote-prone essayist got the thumbs up from Balakian Award winner Steven Kellman, who called George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” a “potent antidote to the toxins of the ambient gibberish. At a time when ‘eloquence,’ what the governor of Alaska dubs ‘verbage,’ is scorned as ‘elitist,’ and cacology is flaunted as a mark of authenticity, words become a tool of obfuscation, manipulation, and oppression.” (Blogger and critic Nigel Beale held out for 1984 as a textbook example of “how quickly massive changes in allegiance take place.”) D.M. Morrison, meanwhile, expressed a preference for the more acidulous H.L. Mencken: “Here’s a vote for On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe, a collection of the great cynic H.L. Mencken’s political writings, fresh as the day they first appeared in the Baltimore Sun. It’s worth reading for this insight alone: ‘As democracy is perfected, the office of President represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.’”

There were also some pleas on behalf of several big-canvas works of political nonfiction. With both candidates making their last-ditch demands on our increasingly frayed attention span, Richard Ben Cramer’s What It Takes: The Way to the White House struck two members as more apropos than ever. Derek Catsam, who teaches history at the intriguingly named University of Texas of the Permian Basin, strongly recommended Ben Cramer’s “epic treatment of the 1988 presidential election from the primaries onward (almost inarguably the single best book of its kind), and Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72, which serves as a reminder not only of Thompson’s sui generis nature, but also of his remarkable political insight beneath all of his bluster and chaos.” And Steve Weinberg called What It Takes “the most insightful book known to me” on our quadrennial executive slapdown.

Kel Munger, Book Editor at the Sacramento News & Review, pointed readers toward Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Again, he wondered whether the Nixon era might not be a dreary blueprint for some of the less savory features of our own: “There’s not much difference, it seems to me, between Nixon’s ‘silent majority’ and Gov. Sarah Palin’s ‘real America.’” Meanwhile, Hans Ostrom, who teaches English at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, hit the fast-forward button and suggested James Bamford’s recent The Shadow Factory: The Ultra-Secret NSA from 9/11 to the Eavesdropping on America. The promotional efforts on behalf of the book have understandably focused on warrantless wiretapping, but Ostrom argues that “there are deeper narratives here about ways in which timidity, overreaction, incompetence, dedication, good intentions, and miscommunication all converge to create many of the ‘intelligence,’ civil-liberties, and foreign-policy messes in which we find ourselves. It’s a much subtler book than most people may think.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that many members looked to nonfiction as a skeleton key to American politics. But fiction and even poetry had its adherents as well. For several respondents, Sinclair Lewis was the man. As Andre Bernard put it: “To this day, no writer has better captured the hypocrisy, the lying, the narcissism, the self-interest, and the mendacity of American politicians—and the people who vote for the liars—than Lewis. Babbitt (about the mindless yet consuming quest for money and respectability of a group of strivers in a Midwestern city), Main Street (how conformity and social hypocrisy poisons a marriage and an entire town), and Elmer Gantry (the rise of a corrupt, politically ambitious evangelical)—these three books sum up the suffocation of ideas by the need for so-called normalcy. And then there’s It Can’t Happen Here, a strange and chilling book about a fascist takeover of the United States by a smooth-talking politician…. Lewis had a gimlet eye for phonies, and there’s no phony like a wrap-yourself-in-the-flag, God-and-country-first, let-business-be-business-and-we’ll-all-prosper politician. You must read him.” Brooke Allen seconded that emotion: “I don’t think that Sinclair Lewis’s great novels Main Street and Elmer Gantry have ever been superseded as portraits of American culture, political and otherwise. We have changed a lot since the 1920s—but in so many ways we have not changed at all.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that many members looked to nonfiction as a skeleton key to American politics. But fiction and even poetry had its adherents as well. For several respondents, Sinclair Lewis was the man. As Andre Bernard put it: “To this day, no writer has better captured the hypocrisy, the lying, the narcissism, the self-interest, and the mendacity of American politicians—and the people who vote for the liars—than Lewis. Babbitt (about the mindless yet consuming quest for money and respectability of a group of strivers in a Midwestern city), Main Street (how conformity and social hypocrisy poisons a marriage and an entire town), and Elmer Gantry (the rise of a corrupt, politically ambitious evangelical)—these three books sum up the suffocation of ideas by the need for so-called normalcy. And then there’s It Can’t Happen Here, a strange and chilling book about a fascist takeover of the United States by a smooth-talking politician…. Lewis had a gimlet eye for phonies, and there’s no phony like a wrap-yourself-in-the-flag, God-and-country-first, let-business-be-business-and-we’ll-all-prosper politician. You must read him.” Brooke Allen seconded that emotion: “I don’t think that Sinclair Lewis’s great novels Main Street and Elmer Gantry have ever been superseded as portraits of American culture, political and otherwise. We have changed a lot since the 1920s—but in so many ways we have not changed at all.”

There were also several boosters for Gore Vidal. Said Bob Hoover, Book Editor at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “It’s a no-brainer to pick Gore Vidal’s Burr, his trenchant, take-no-prisoners vision of American politics dominated by cynicism and lies—in 1800—during this presidential campaign driven by empty slogans, phony ‘Joes,’ and one candidate pandering to moderate-income voters with his eight houses. The rest of Burr’s ‘Empire’ novels are equally cynical and perhaps a little goofy about the 20th century, but it’s hard to name another novelist with such concern for the politics of the country.” Goofy, you say? Michael Pinker begged to differ, anointing the last novel in the series as the best: “America’s best political novel, The Golden Age, from our best political writer, Gore Vidal, holds the mirror up to our own era with coruscating wit and grace…. Why does anyone take our politics seriously, save those who suck their substance from it? As once again in this election season they loudly hawk policies from which their backers and minions profit no matter who holds office, our Solons enact the farcical spectacle of the vaunted two-party system, an outmoded, hugely extravagant con game which Vidal himself has dubbed one party with two names. If the plot of this novel may prove thin at times, its excoriation of the contemporary fashion in government leaves no doubt of how much we need change and reform, as well as how little we are likely to get what is best for all the people, as opposed to the privileged few, no matter who wins on November 4.”

After that, though, the fiction consensus broke down. A multitude of titles was lobbed over the transom. Todd Shy, who reviews for the Raleigh News and Observer, put in a good word for Roberto Bolaño’s recent 2666: this “sprawling, relentless, unfinished novel holds America in a larger historical gaze—and sees everything. Gogol’s famous outburst about a ‘brisk, unbeatable troika racing on’ looks like Russian prophecy: he intuited a Bolaño to come. America, hold tight.” Rikki Ducornet turned cartwheels for Rick Moody’s “extraordinary Purple America, in which the filiation between lethal families and toxic societies is brilliantly revealed.” Katharine Weber heard the dystopian echoes in Sarah Palin’s voice: “Every time I hear Sarah Palin speak, the shock of recognition is vivid and immediate—she has sprung to life from the pages of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.” For Myrna Lippmann, Richard North Patterson’s 2007 novel The Race was not only a page-turner but a vivid demonstration of “how complicated—and sometimes arbitrary—the process for selecting the next leader of the most important country in the world is.” And Leora Skolkin-Smith put in a pitch for both Grace Paley and the political (sometimes) fabulism of Donald Barthelme: “What they wrote really was an reinvention ‘political writing.’ I fear their legacy has been overshadowed by more contemporaneous writers and we’ve lost that thread of literary continuum.”

After that, though, the fiction consensus broke down. A multitude of titles was lobbed over the transom. Todd Shy, who reviews for the Raleigh News and Observer, put in a good word for Roberto Bolaño’s recent 2666: this “sprawling, relentless, unfinished novel holds America in a larger historical gaze—and sees everything. Gogol’s famous outburst about a ‘brisk, unbeatable troika racing on’ looks like Russian prophecy: he intuited a Bolaño to come. America, hold tight.” Rikki Ducornet turned cartwheels for Rick Moody’s “extraordinary Purple America, in which the filiation between lethal families and toxic societies is brilliantly revealed.” Katharine Weber heard the dystopian echoes in Sarah Palin’s voice: “Every time I hear Sarah Palin speak, the shock of recognition is vivid and immediate—she has sprung to life from the pages of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.” For Myrna Lippmann, Richard North Patterson’s 2007 novel The Race was not only a page-turner but a vivid demonstration of “how complicated—and sometimes arbitrary—the process for selecting the next leader of the most important country in the world is.” And Leora Skolkin-Smith put in a pitch for both Grace Paley and the political (sometimes) fabulism of Donald Barthelme: “What they wrote really was an reinvention ‘political writing.’ I fear their legacy has been overshadowed by more contemporaneous writers and we’ve lost that thread of literary continuum.”

And speaking of that literary continuum, wasn’t the dusty old canon overlooked? Not completely. Ted Gioia spoke up on behalf of Henry Adams: “Democracy, first published in 1880, still seems very timely today. You would almost think that the author had been witnessing the congressional deliberations over the recent bailout bill.” Deirdra McAfee saw our contemporary dilemmas mirrored quite precisely in Chapter 25 of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. “At this point in the novel,” she wrote, “Moscow is soon to be invaded by Napoleon; everyone who can do so has deserted the city, leaving no one but the poor and the ignorant. Count Rostopchin, who is both vain and helpless, needs someone to blame and punish—various leaders and citizens in America today also seem to be seeking the same, whether foreign enemies, Wall Street fat cats, or political opponents.” And Bruce Allen, a freelancer out of Kittery, Maine, turned to Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, in the new Julie White translation: “This great, sentimental tidal wave of a book dramatizes—more forcefully than does any other classic novel—the fate of the working class poor in an uncaring society ruled by great wealth and power safely removed from the claims of the everyday world. The forces responsible for America’s ruinous last eight years might not have to worry about the guillotine. But the righteous anger that justly accompanies the unforgettable story of Jean Valjean’s purification through suffering is a salutary corrective, and perhaps a prophetic warning.”

Poetry, too, got the nod from Walton Muyumba of Dallas, Texas, who testified on behalf of Kevin Young’s Dear Darkness: “These new elegiac and funny poems move on me, tugging on my guts and yanking my earlobes. At a moment when political rhetoric is jangling indelicately around us, Young’s soulful lyrics are hard-bop Palin-cleansers.” (Hans Ostrom, already mentioned above, did his bit for Emily Dickinson and Langston Hughes: “In especially tough times, poetry is especially good for the soul, and even people who don’t regularly read poetry—or who may even feel allergic to poems—will get something out of works by these quintessentially American poets, who are earthy, witty, wise, and resilient.”)

And that, ladies and germs, leaves the fine art of graphic storytelling. Michael Lindgren directed a terrorist fist-bump at David Rees’s Get Your War On, a collection of crude cartoons that “began circulating on the Internet in October 2001 and were subsequently collected in this slim volume from Soft Skull. Although the references are dated, the ranting of Rees’s bitter, fearful, confused, none-too-bright avatars more accurately reflects the American body politic than a shelf-full of sober book-length analyses.” Which brings us back to Sara Paretsky, who ultimately stiff-armed Hofstadter and even Mark Twain in favor of (drum roll, please) Pogo.

“Unfortunately he’s out of print,” she writes, “but the website reprints some of the books a chapter at a time, and he did give us the famous, ‘I have met the enemy and he is us,’ which started as the longer ‘Resolve, then, that on this very ground, with small flags waving and tiny blasts of tiny trumpets, we shall meet the enemy, and not only may he be ours, he may be us.’ [Walt] Kelly had the courage to create that particular sequence during the height of the McCarthy scare, with the figure of Simple J. Malarkey as a stand-in for McCarthy. During the last eight years, we’ve been subjected to fear-mongering of unendurable intensity, and McCain and more especially Palin seem determined to promote and deepen the Age of Fear with their Wehrmacht style rallies, rousing crowds to yell ‘kill him,’ and reducing the blogosphere to hysterical cries of ‘Terrorist’ and ‘Communist. Walt Kelly was the perfect antidote to the fears of the McCarthy era. Today, we have the Daily Show and Doonesbury, but neither of them really comes close to the Swamp as the perfect metaphor for American life.”

“Unfortunately he’s out of print,” she writes, “but the website reprints some of the books a chapter at a time, and he did give us the famous, ‘I have met the enemy and he is us,’ which started as the longer ‘Resolve, then, that on this very ground, with small flags waving and tiny blasts of tiny trumpets, we shall meet the enemy, and not only may he be ours, he may be us.’ [Walt] Kelly had the courage to create that particular sequence during the height of the McCarthy scare, with the figure of Simple J. Malarkey as a stand-in for McCarthy. During the last eight years, we’ve been subjected to fear-mongering of unendurable intensity, and McCain and more especially Palin seem determined to promote and deepen the Age of Fear with their Wehrmacht style rallies, rousing crowds to yell ‘kill him,’ and reducing the blogosphere to hysterical cries of ‘Terrorist’ and ‘Communist. Walt Kelly was the perfect antidote to the fears of the McCarthy era. Today, we have the Daily Show and Doonesbury, but neither of them really comes close to the Swamp as the perfect metaphor for American life.”

What you have just read is, by the way, just the tip of the critical iceberg. We will be running additional posts over the next couple of weeks with individual, “Long Tail” suggestions by other members. In the meantime, please do pile into the comment thread with ideas of your own—and be sure to vote for your other favorite come Tuesday.