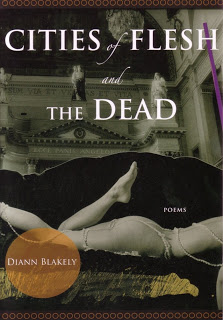

Cities of Flesh and the Dead, Elixir Press, 2008.

Diann Blakely is the author of three books including Hurricane Walk and Farewell, My Lovelies. The recipient of the Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America, she served as poetry editor of Antioch Review for a dozen years and is the co-editor of Each Fugitive Moment, a collection of essays on the late Lynda Hull. She lives south of Savannah with her husband, the author Stanley Booth.

In this collection, you dedicate a number of poems to late poets, such as Anthony Hecht, Lynda Hull, William Matthews and Herbert Morris, and you invoke the stories of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, though there’s a less personal connection with the latter two. The mortality of the artist is indeed a pulse that runs through the work. And then there are the startling lines in the poem “Blood Oranges”: “I’ve attended so many funerals,/ Dressed in stiff-collared black, that I revise/ My bedtime prayer, also terrified I’ll die/ Before I wake. Everything’s inherited here.” Can you speak about this book’s preoccupation with life and death, or, as you write it, “love and loss”?

Love and loss have come to seem synonymous, at least to me. Such knowledge is neither an unlucky nor, so to speak, an unlovely thing: when I was in my early twenties, reading incessantly, and attempting my first real poems, I wondered—somewhat impatiently—why even the writers I loved most, like Lowell, seemed so obsessed with mortality when scarcely older than I was. (“Being half in love with easeful death” was easy to understand with poets of earlier eras like Keats, who had lost his mother at a young age to tuberculosis, nursed his brother until his demise from the same disease, then begun seeing its first signs in himself at the same age I was; and also with Dickinson, whose own time had such a frighteningly high rate of childhood mortality and herself lost many early friends; Lowell’s students Plath, as I of course knew, had killed herself at thirty, and Sexton at forty-six, but suicide was a near life-long preoccupation with them both.) I was simply too ignorant to realize how quickly we begin losing the people we love. My forties were full of these losses, hence the poems in Cities of Flesh and the Dead dedicated to those I consider my cherished late friends and masters. Each is a person from whom I learned an incalculable amount. Perversely, it was Bill Matthews, who died at fifty-five, just four years older than I am now, who told me that one spends the first half of one’s life saying hello and the second half saying goodbye.

“Grief” and “rage” and “dread” are touchstone words that recur in his poems, but one of the most valuable lessons he taught me about life—the lessons he taught me about poetry are too numerous to list—is the abiding love and consolation to be found in friendship. Especially friendship between poets. No group of artists is as marginalized in our culture. As I imply in “Afterwords,” while it’s ridiculous to think we can prevent loss through mere postcards, and now e-mails, we can “mute [each other’s] howling loneliness.”

I feel heretical in contradicting Elizabeth Bishop, but I don’t think that attempting to master the “art of losing” has much to do with—to use her italics—writing it. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe writing about the things we lose is an act of commemoration—to use another term of hers—and celebration in itself. Grief alone is inevitable, but merely a first step. We must reach the state where mourning is overcome and celebration of being privileged to be part of another life becomes primary. This is what I hope the poems dedicated to Matthews, Anthony Hecht, Lynda Hull, and Herbert Morris accomplish.

How sad I am that Jerry Wexler, former head of Atlantic Records with Ahmet Ertegun and dear friend of mine in his later years, died just as I was getting ready to send him a copy of Cities. I didn’t know Jerry when I wrote the poem about Pretty Baby, but later, in the course of a phone conversation, I learned that he produced the Oscar-nominated soundtrack for that film, seeking out James Booker and the members of the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra rather than using Hollywood session musicians. “Sweetheart,” he said, “there’s no water that tastes as good as the kind that comes from original source.” At least I was able to send him the galley page with his name on it, and a brightly lipsticked kiss from me.

The opening and closing sections in the collection are called “Exiles and Returns” and “Solos and Duets,” respectively, which echo a number binary pairs (like the aforementioned “life and death” and “love and loss”). But there’s a noticeable contrast in two of your poem structures: the compressed sonnet and the lengthy lines of the more narrative poems like “Bad Blood,” “On the Border,” and “Antidepressive.” How do you negotiate the subject with its form? How do you determine if a poem works better with or without short, tight lines?

The long-lined poems are actually long-lined / short-lined poems in strict syllabics, a fifteen/five pattern that seems to me ideal for the sometimes dizzying experience of various kinds of travel, which yanks us out (the long lines) of the smallness of ourselves (the short lines) and then finally returns us to ourselves changed, which I hope is made clear in the final lines of each of these poems. “Bad Blood” roams the country’s recent disasters and plagues, from AIDS to 9/11 to Katrina; and something similar happens in “The Triumph of Style,” which veers from Hitler’s Germany to the disastrous landfall of Hurricane Andrew in Miami in 1992 (ironically, the box containing my author’s copies of my first book, Hurricane Walk, arrived on my doorstep that same day, and I’m typing as tropical storm Fay roils the waters of the Little Satilla River just outside my home in south coastal Georgia); and the poem from which Cities of Flesh and the Dead’s title is taken, “Before the Deluge: Solo in New Orleans.”

But travel—which has its roots in the French word “travail,” and we all know what that word means in English—can be internal as well, a voyage through mind and memory and the present tense, as in “On the Border,” “Antidepressive,” and “Objects of Desire,” the last of which zig-zags from childhood to movies to questions about both sexual orientation and the devastatingly high cost placed on appearance in our culture.

The sonnets, usually in sequences of varying length, seem more in the nature of movie scenes, or, to be more specific, juxtaposed movie scenes. Why choose one form over the other? I honestly don’t know. Forms, like subjects for poems, often choose the writer, not vice versa. I’m very careful, when beginning to write, to take the time to allow the poem to dictate to what form (an often maddeningly slow process!), not to impose a preconceived one on material.

There are a number of knives and blades and dangerous sharp objects in the pages of this book. There are a number of threats and fears and anxieties. The vulnerability of the flesh and spirit radiates outward into the vulnerabilities of culture and history. The line “Taking notes as if the world might disappear” resonates with the many ways the poems in Cities of Flesh and the Dead take stock of things ephemeral and exposed. Are those qualities what make humans and humanity so precious? Are these human-made cities and societies, “the fallen raptures of this murderous world,” to be remembered, or reconsidered?

To be remembered and considered. And then re-remembered and re-considered, if that makes sense.

Perhaps some personal narrative will clarify my meaning. I was born in Anniston, Alabama, in 1957, the place and year in which the first Freedom Riders’ bus was burned; my childhood and adolescence were spent in Birmingham, site of some of this country’s worst violence during the Civil Rights era, including the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church and subsequent murder of four young African-American women (Spike Lee’s 4 Little Girls is perhaps the best work in any genre on the latter); I vividly remember watching the funeral of President Kennedy on television, then the violence that erupted around the country in the wake of Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s assassination, then the live broadcast of Robert Kennedy’s killing in Los Angeles. In 1972, the racist and much-despised—in my household, at least—governor of Alabama, George Wallace, during his own bid for the presidency, was the victim of a shooting that left him permanently paralyzed from the waist down. The first newspaper and magazine articles I remember reading contained, respectively, the initial interviews with POWs with their horrific accounts of torture at the hands of the North Vietnamese and—talk about juxtapositions!—the fatal mauling of two young women by grizzly bears in Yellowstone Park. Walter Cronkite offered nightly what Lynda Hull called “the roll call of war dead,” as well as footage of napalmed villages and their inhabitants, not to mention the trial of Lt. Calley after the massacre at My Lai. I didn’t know that I was growing up during a particularly violent era in our nation’s—indeed, the world’s—history; I assumed that life had always been that way and always would be.

Which, as I think about it, wasn’t a wholly erroneous assumption. Neither, I should imagine, is my assumption that anyone who came to full consciousness in the South of my childhood could fail to be obsessed by race and class, however cliched those terms have become. Many of the historical and cultural tensions—even certain, more subtle forms of violence—of the time were mirrored within my own family; I don’t think any of its members were particularly well equipped for the lives they found themselves leading or being raised within. Yet all the while, during this period of my life, I reveled in the pleasures and joys a child takes in her fleshly existence, fettered only, of course, by parental and social strictures. Who knows better, if unconsciously, than a child Stevens’ particular wisdom: “The greatest poverty / Is not to live in a physical world, / To feel one’s desire is too difficult to tell from despair.” To be in despair at any age is to be stuck in a nightmare, one that can kill. Yet actual poverty continues to be ubiquitous, also violence; as I became older and encountered Wallace Stevens, I realized that I’d always somehow known that “poetry”—or the coupling of what he called “nobility” and the imagination in “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words”—“is the violence from within that protects us from the violence from without.” I realize that Steven’s use of the word “poverty” in the first quotation may seem overly lofty, if not downright ridiculous, when set against images from, for example, of Darfur. I also realize that it may seem contradictory, at best, to say that nightmares can be any form of protection, but nightmares can be a form of courage, or “nobility,” in that they confront what is real. Sometimes they coax us to greater self-knowledge, which, in turn, can lead us to greater, more informed empathy and compassion. Sometimes they enable us to bear witness to the world more deeply and broadly. Sometimes they’re meant to be transcended. In any event, I can say without fear of self-contradiction that poetry saved—and continues to save—my life.

*