Now You’re the Enemy, University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

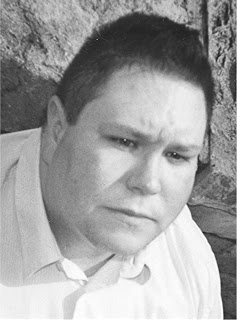

James Allen Hall is assistant professor of English at Bethany College in West Virginia. Now You’re the Enemy was a finalist for the Walt Whitman Book Award and a semifinalist for the Crab Orchard/Open Competition Book Award. He’s the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize and three Pushcart Prize nominations.

A mini-essay from the poet and scholar:

“In The Ruins of Confession”

1. Dear Dr. Freud,

I have had to kill you.

Confessional poetry ain’t got a thing if it doesn’t swing a taboo over its shoulder, beat it bloody, and throw it into the river. Freud proposes two “universal” taboos: patricide and incest. These, he says, are the driving forces behind the individual’s psyche and the blueprints for social organization.

The confessional poem first establishes a power dynamic, then reverses that dynamic to inscribe the speaker with all law-making jurisdiction. In “Daddy,” Plath meets both of Freud’s taboos head on, committing first patricide then incest. By poem’s end, the speaker is a vampire-slayer with a killer lyric vocabulary. The Confessionals understood selfhood as constructed within certain regulatory matrices, those that place the subject before the door, waiting for Law to grant it authority. Poets like Plath one-up Whitman—they “unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs.” The I is implicated: “I myself am hell,” as Lowell says. The confessional poem is not just “about” taboo: it offers the possibility of revolt.

2. “I” is the greatest lie ever told.

The Post-Confessional poem destabilizes power dynamics by privileging an ecstatic self—one which performs that self while noting its performance. Cate Marvin’s “Lying My Head Off” is a perfect example of a Post-Confessional speaker who makes of her admissions a collage, which Marvin then ironicizes. The poem begins by pointing to the speaker’s head, “in a dank corner off the yard./ I lied it off and so off it rolled.” The headless speaker confesses to hating a beloved, to teaching children obscenities and then buying them alcohol. The poem progresses by offering other versions of what happened, by negating the speaker’s original claims, by indicting the self as an unstable vessel for Truth (“I would have sworn in court that I believed/ myself and then felt guilty a long time after”), by becoming “an other self.” The self becomes “an other” by learning

another language. It translates easily.

Here’s how: What I say is not what I mean,

nor is it ever what I meant to say.

You must not believe me when I say

there’s nothing left to love in this world.

Sharon Olds’ title poem “Satan Says” operates along similar lines. The speaker, locked in a box, follows Satan’s advice in order to free herself. She engages the taboo by using vulgar words, especially to describe her parents’ sexual organs, but there’s no real confession. When prompted to say “what happened to us in the lost past,” the confession is spoken by Satan, that storied liar: “Now say torture.” The poem outlines the difficulties of saying the unsayable, of annotating the long silences around fear. These delicious ironies amount to metaphors stacked upon metaphors; we are shown how an ecstatic self lives in unstable times.

3. Tradition and Form

I’m enamored of how formally inventive post-confessional poets have gotten. Certainly, the Confessionals prefigured these kinds of poems: Plath’s use of nursery rhyme, Sexton’s re-envisioning of fairy tale, Lowell’s early gesture in Life Studies at hybrid genre.

Miguel Murphy’s poem “Love Like Auto-Sodomy” flirts with taboo in its title, which also sets us up for a love poem. But instead, the poem praises the opposite: “You have to hate// until you hurt no more. You have to be somewhere else./ You have to close your eyes to even bear me at all.” The form that we expect (boy meets boy, boy loses boy, boy drowns his sorrows at a martini bar where he meets a far more beautiful boy) is refuted. Murphy’s confession (that “pelvicly is the only way I know/ to heal”) creates surprise at the same time that it updates the tradition.

Michael Dumanis’ love poem, “These Amorous Intents,” deploys form to ironic, darkly comic, and devastatingly serious effects. In the first section, we meet a voice who promises to do various things for the beloved, but is ultimately powerless to perform more than the speech-act. In the third section of the poem, a Q&A proceeds in which the speaker eludes the Questioner. Its opening question, “Q: Are you sick with self-pity?” anticipates the critiques that Confessional poetry has weathered. The speaker answers with a nice bit of post-confessional sabotage: “At the masked ball, no one noticed me.” The speaker evades the confessor.

4. Who You Calling Post-Confessional?

More than a handful of times, I’ve heard “confessional” bandied about in order to diminish autobiographical poems. No one, it seems, wants to be “merely” confessional—the fear is that one’s art is evocative only because it treats powerfully emotional material (i.e., the taboo, the transgressive). The poem is “good,” the label seems to say, only because the experience described was harrowing—the poem makes a spectacle of experience, not language. Indeed, this is what Aristotle rants against in his Poetics, saying that spectacle is the domain of stage directors, and thus antithetical to poetry. But for many poets, myself included, the pejorative connotation never made much sense. I washed my eyes in Plath’s Collected Poems, and if she was Confessional, then that was what I wanted to be when I grew up.

Jeffrey McDaniel, writing for the Poetry Foundation’s blog, identifies post-confessional poems as those which “enter into a place of psychic fracture, often involving family, and elaborate on or develop techniques used by the confessional poets.” I’d add that the post-confessional poem often deploys ironic speakers, pastiched forms, narrativity inflected or made entirely by disjunction, and images that temper the autobiographical impulse with the surreal. There’s a trend toward multi-vocality in post-confessional work, a preponderance of “I”‘s that don’t add up. The subject matter need not be traumatic; indeed, it seems that the post-confessional poem first flirts with, then utterly thwarts, the notion of taboo. If Marvin’s speaker is/is not to be believed, and if there is nothing left to love, then we are free to love everything, in whatever beautiful language we can cobble from the ruins.

Works Noted:

Aristotle. Poetics. Penguin Classics, 1997.

Dumanis, Michael. My Soviet Union. University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

Lowell, Robert. Life Studies and For the Union Dead. FSG, 1967.

Marvin, Cate. Fragment of the Head of a Queen. Sarabande Books, 2007.

McDaniel, Jeffrey. “Post-confessional Poetry?” June 17, 2007.

Murphy, Miguel. A Book Called Rats. Eastern Washington University Press, 2003.

Olds, Sharon. Satan Says. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980.

Plath, Sylvia. Collected Poems. Harper Collins, 1981.

Works Recommended:

Davis, Olena Kalytiak. And Her Soul Out of Nothing. University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Flynn, Nick. Some Ether. Graywolf Press, 2000.

Graham, David and Sontag, Kate, eds. After Confession: Poetry as Autobiography. Graywolf Press, 2001.

Rankine, Claudia. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely. Graywolf Press, 2004.

Trethewey, Natasha. Bellocq’s Ophelia. Graywolf Press, 2000.