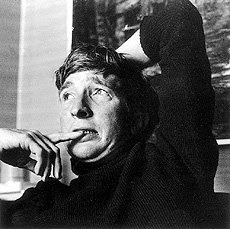

The following essay from Kansas City Star books editor John Mark Eberhart begins In Retrospect series’ look at John Updike’s 1981 NBCC winner, “Rabbit is Rich.”

My introduction to John Updike’s work came courtesy of a history course I took as a junior in college. Said course focused on America in the 1960s and early 1970s. God bless my brilliant professor, though I have forgotten his name. One of the “textbooks” he assigned us was Updike’s “Rabbit Redux.”

I bought it at the University of Missouri bookstore, took it back to my room and, curious as to why a history professor was assigning a novel, cracked it open.

I finished it before sunrise and I’ve never been the same. Updike’s cinematic, journalistic style certainly appealed to me, but what was even more impressive was his firm grasp of American life, with all its foibles, failures and, yes, epiphanies and ecstasies.

I was born in 1960, which is to say that I actually remember the Sixties because I was too young for chemicals. But I remember that time from a child’s viewpoint. Reading “Redux,” which was set in 1969, was like running into an old friend and realizing you never really knew that person the way you thought you did.

“Redux,” published in 1971, was the sequel to “Rabbit, Run,” published in 1960. But Updike was just getting started. “Rabbit Is Rich” came in 1981 and “Rabbit at Rest,” which saw print in 1990, completed the life story and the oh-so-American story of one Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom – lecher, dreamer, fool, Everyman sage, car salesman, seeker.

I think one reason Updike’s work pleases me so much is that I believe writers are supposed to get better – and that’s exactly what Updike did through the decades during which he wrote the Rabbit series (which also includes a worthy postscript, by the way; you’ll find the novella “Rabbit Remembered” in Updike’s “Licks of Love” story collection).

“Rich” and “Rest” both won Pulitzers, the coveted prizes that eluded the first two volumes. And “Rich” swept the major book honors for work published in 1981, including the National Book Critics Circle Award.

“Rabbit Is Rich” remains one of my favorite novels. To be honest, my list of the half-dozen greats varies depending on which day you ask me, but this one is always on there.

The other three Rabbit books are tragedies. In them, children drown and burn, marriages break up or come close to doing so, and, in the final novel, Rabbit’s own heart literally breaks; in “Rabbit at Rest,” we see the former high-school basketball star as a corpulent and increasingly irrelevant man. Out of touch with his own time, he turns more and more, as the novel progresses, to the songs and rhymes and memories of his youth. But he still loves sex enough to sleep with his own daughter-in-law, driving yet another emotional nail into the coffined heart of Janice, his wife.

“Rabbit Is Rich,” though, is the comedy of this tetralogy, and its high spirits give it a different edge. In these pages, Updike gets up to all kinds of highjinks, resulting in both a stunning literary novel and an exhilarating read.

Rabbit, formerly a Linotyper, has inherited his chintzy father-in-law’s position as front man of a Toyota dealership in fictional Brewer, Pennsylvania. It’s 1979, and as the energy crisis deepens and the American dollar turns to mush, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom couldn’t be happier. Those Toy cars get great gas mileage, and Rabbit is getting richer by the day from their sales. Leave it to Updike to take a sort of perverse glee in the nation’s economy going to ruin. But hey, this is America, and no matter how nasty times get, there’s always a salesman of some kind out there who remembers how to make a buck.

When he’s not peddling imports, Rabbit’s at home jousting with stubborn Janice and her mother Bessie, who unlike Rabbit’s late father-in-law Fred refuses to kick the bucket just yet. But the novel’s true first crisis looms in the form of the homecoming of Nelson, Janice and Rabbit’s sullen college-age son. Nelson never has forgiven his father for what he sees as Rabbit’s unpardonable sins: Letting the hippie girl Jill burn to death in “Redux” and letting Becky, Nelson’s infant sister, drown in “Run.” Forget the fact that Rabbit wasn’t present when either accident happened; every family needs its scapegrace, and Rabbit, guilty by association but determined to get what he can out of life, lives out that role in the Angstrom universe.

Despite the tension, the book has a charming, almost magical feel – and it is shot through with rituals and rites of passage. Nelson, whether he likes it or not, is his father’s son; he has knocked up his girlfriend Pru just as Harry knocked up Janice. Thus there’s a wedding – at which Rabbit, to his great surprise, finds himself weeping, perhaps for Nelson’s vanishing youth and certainly for his own.

There’s also the “Flying Eagle” bunch – a jolly crew of middle-aged pirates and their wives, fellow members of the country club Rabbit now has the means to enjoy. With this collection of aging miscreants of American commerce – one’s a construction contractor, another sells insurance; they all seem to share the belief that you’d better screw the government before the government screws you – Harry and Janice drink, fuss and fornicate. And even find time for a little sport – golf for Rabbit, tennis for Janice.

Updike makes the most of the comic possibilities here. At one point, pregnant Pru is injured in a fall. The following morning, Rabbit reflects how terrible he would have felt if she’d suffered worse than a broken arm, for at the time, Rabbit and Janice and their Flying Eagle cronies were at a strip club, watching a naked girl tickle her own ass with a feather. Nelson, hearing this, is appalled and angry; here he is saddled with a gravid, gassy and now injured spouse while his feckless parents are out partying. The injustice!

How powerful a writer is Updike? Well, I was 22 when I read “Rabbit Is Rich” – just about the same age as petulant, pesky Nelson. Yet never once did I identify with him. Rabbit with all his faults – his womanizing, his shallow politics, his cocksure certainty that life should be a ribald play with himself at center stage – was nevertheless our stalwart hero, the one whose rangy, athletic, supple thoughts we were allowed to listen in on. Rabbit’s saving grace always was his rather innocent faith in … oh, you name it – God, America, cars, music, “Consumer Reports” magazine and, most movingly, the landscape itself. Whether swimming in a murky Poconos pond or jogging down the gritty streets of Brewer and Mt. Judge or sunning himself in the tropics while ogling the brick-house wife of his Flying Eagle pally Web Murkett, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom was at home, at ease, at play, at large in the world. In the next book, of course, he would be “at rest,” but the title of the more downbeat fourth book would be deeply ironic.

I’m not sure I wanted to be Rabbit Angstrom, but even at that young age, I was pretty sure I’d become more like him as time passed. And I’m afraid I have. Thankfully, I’ve avoided some of his worst peccadilloes. Or maybe I haven’t. My wife told me recently that I seem less narcissistic these days – but I immediately began brooding, narcissistically, on the question of how self-centered I must have been for so long. That aside, I readily admit that, like Rabbit, I like a good rainstorm; it keeps the world nailed down. I like things – houses, cars, my workspace – tidy, and wish sometimes that human relationships could be so clean. God help me, I’ve taken up golf, which I never had the patience for when I was young. Most alarming of all, the songs and films and books of my youth often seem more vivid to me than do the current fabrications of the Cultural Machine.

John Updike has said of Rabbit Angstrom that the character provided him with a kind of window on the American dream. In one of my interviews with him, Mr. Updike observed that without Mr. Angstrom, he would have won “almost nothing” in terms of literary prizes, although “The Centaur” got its due. In addition, it’s hard not to see Harry as John’s alter ego. Both men play golf, believe in God but question his ways, and share, I think, a view of life that is more smile than grimace.

I don’t know if “Rabbit Is Rich” is Updike’s greatest book. “Of the Farm” is a small marvel and “Rabbit at Rest” is an elegiac summation and “Americana” is a pretty remarkable collection of poems and “The Early Stories” collects some of the author’s most important short fiction. But I do believe Rabbit, the character, is Updike’s greatest single creation, the achievement for which he’ll most be remembered.

Near the end of “Rabbit Is Rich,” a child is born – a granddaughter, Rabbit’s granddaughter, his. His flesh and blood recreated, once again. His. The melancholy and the pain of “Rabbit at Rest” lie some years in the future; Harry, like us, does not know what challenges and disappointments await him. Thank heaven for that, yes? It is our curse to be lustful, hungry and human; much worse, though, would it be to know the petty torments or diabolical damnations that Trickster Fate has in store.

Better, at day’s end, the pleasures of life. Of love, of the night air, of a good book – or even four of them – about a flawed, fantastic man, a man twitchy and restless and alert and exasperating enough to be nicknamed Rabbit.

Often, I have revisited the Rabbit books. Even when many months have passed without my doing so, though, they stay with me. A man named Updike made them. After all this time, though, they’re really ours, aren’t they? Ours. Pages and pages, turning, turning, with the years. Ours.

John Mark Eberhart is books editor of the Kansas City Star.