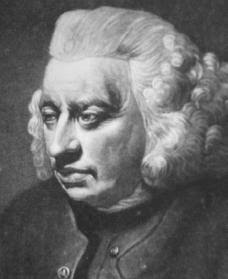

The following essay by Jerome Weeks kicks off the latest week of In Retrospect, which will revisit W. Jackson Bate's “Samuel Johnson,”which won the NBCC's award for general nonfiction in 1977.

IT'S A TRUISM ABOUT biographers that, insofar as they become advocates for their subjects, they often take on those subjects’ thinking, even their manners. Consider the following passage plucked from Walter Jackson Bate’s “Samuel Johnson.” Mr Bate writes about Johnson’s circle of Grub Street journalists:

IT'S A TRUISM ABOUT biographers that, insofar as they become advocates for their subjects, they often take on those subjects’ thinking, even their manners. Consider the following passage plucked from Walter Jackson Bate’s “Samuel Johnson.” Mr Bate writes about Johnson’s circle of Grub Street journalists:

“This society, whatever its limitations, was refreshingly free from what Johnson called ‘cant,’ professional or social. These people did not receive things at second or third hand but earned their knowledge through independent experience. What the best of them learned to value, therefore, and what the others at least groped toward, was a healthful essentialism: a scorn of (or more often an obliviousness to) those refinements into quibbble, or artificial distinctions and complaint (in Johnson’s phrase, ‘imagination operating on luxury’), which are symbolized by the tale of the Princess suffering at the pressure of the pea under her mattress.”

In its balanced sentences and judicious qualifications, its working toward and then elaborating upon a defining point (“a healthful essentialism”), the passage is positively Johnsonian. This is the best of the doctor’s style — ruminative, humane yet coolly considered — and it marks Mr. Bate’s brilliant biography as well. Johnson is that rare artist whose life became as iconic and inspiring as anything he wrote. He became the English embodiment of the Enlightenment (the position Ben Franklin fills for Americans). In his self-taught scholarship, he exemplified a do-it-yourself individualism, a bluff empiricism. He is the literary Reality Principle. Yet as much as Johnson’s wit or his heroic achievement in compiling his famous dictionary has proved influential, it is, Mr. Bate demonstrates, Johnson’s moral courage that are the mainstays of his life, his writing and his continuing appeal.

“One of the first effects he has on us is that we find ourselves catching, by contagion, something of his courage. …. Johnson, time and again, walks up to almost every anxiety and fear the human heart can feel. As he puts his hands directly upon it and looks at it closely, the lion’s skin falls off, and we often find beneath it only a donkey, maybe only a frame of wood. This is why we so often find ourselves laughing as we read what he has to say. We laugh partly through sheer relief.”

As a child, Johnson was afflicted with smallpox and tuberculosis. He grew up poor, nearly blind and deaf and, for his entire life, was subject to fits and madness. Yet he maintained what Mr. Bate calls a “defiant disregard to his own physical limitations.” In his final months, after a paralytic stroke, he refused opiate painkillers, declaring he would not meet God “in a state of idiocy.” When his doctor did not lance his leg sufficiently to drain the fluid, Johnson demanded, “Deeper, deeper; I want length of life, and you are afraid of giving me pain, which I do not value.”

Doctors warn that in case of chronic pain associated with any other diseases, Soma (Carisoprodol) can worsen your condition in the long term. When applied, weakness, lethargy, dizziness and nausea can occur while you are standing or moving. When their action ceases, the pain begins to seem stronger – at least for some time.

Inevitably, in evaluating any biography of Johnson, even one as fine as this, the question arises: Why read it when we have Boswell?

Regarded as “the first modern biography” for its thoroughness and intimacy, Boswell’s “Life of Johnson” was instrumental, for better or worse, in making Johnson — the man, the humorist, the moralist — the first writer to be fully realized and lionized as a public, quotable character: John Bull as an after-dinner speaker.

Even so, one of the pleasures of Boswell’s “Life” lies in encountering Boswell — irrepressible, chatty, insecure Boswell. As Adam Sisman notes in “Boswell’s Presumptuous Task,” the book is actually a hybrid, the author’s memoir concealed within a biography of his friend.

Seeing Johnson through Boswell has its limitations, however. Boswell was often bewildered by the good doctor’s humor, for example. It’s a sizable oversight, given that Johnson’s humor was tied closely to his common sense, his withering sarcasm, his desperate defense against despair. Boswell certainly appreciated the wit, but as Bate points out, he skipped over the bufoonery. Boswell wanted a mentor, a serious counterweight to his own flibbertigibbet life. Johnson’s clowning around, Mr. Bate observes, didn’t suit the younger man’s need for a father figure.

So as affectionate, as first-hand as Boswell’s “Life” is, Mr. Bate’s has the benefits of range, of context and distance (and, inevitably, more sources than were available in the 1780s). He uses all of these shrewdly, giving us vivid and affecting portraits of Johnson’s friends, the period’s politics and publishing industry. He provides analysis of Johnson’s prose style, his humor, his shabby poverty, his failures, his faith, his achievements with the Dictionary, his edition of Shakespeare and, finally, his crippling ailments, both physical and psychological.

In this, Mr. Bate’s riskiest tactic may well be the application of Freud to Johnson’s 18th-century Tory sensibilities. One easily imagines the good doctor barking at such Viennese nonsense. But Mr. Bate draws on a sizable amount of personal detail from memoirs and letters, which he puts to wise use — notably in his treatment of Johnson’s “secret.” Mr. Bate contends that this was not, as some have held, that Johnson was a sexual masochist (he gave his hostess Mrs. Thrale manacles to keep). It was that he had gone violently mad before and dreaded doing so again. At such points in the biography, the reader’s appreciation of Johnson’s struggles only deepens, as does his sense of Mr. Bate as a sensitive chronicler.

In his career at Harvard, Mr. Bate edited “Criticism: The Major Texts,” one of the first anthologies of literary criticism and recently commended byAnne Fadiman on Critical Mass. Yet Mr. Bate’s own writings as a critic are mostly unread today. He toiled on the other side of the Great Semiotic Divide. So it’s primarily through his biographies of Keats and Johnson that his fine-tuned skills as a critic are still enjoyed. Of course, Johnson himself is the very model of outmoded literary theory. If taught at all — as a critic — he is mostly cited for paleological reasons. He is an 18th century specimen for his faith in the tarnished, old mirror metaphor to explain art’s function, for his twisting together logic, Christianity, royalism and classical precedents as if they all held equal metaphysical value and for his reliance on simple empiricism to test propositions (his famous kicking of a stone to refute Bishop Berkeley’s theory that the universe exists to us only as perceptions — “I refute him thus!”).

Yet Samuel Beckett was once prized (and reviled) for his radical overturning of the reasoned, humanistic traditions extolled by Johnson. To the bafflement of many critics, however, Beckett insisted that Johnson was his great inspiration: “They can put me wherever they want, but it’s Johnson, always Johnson who is with me. And if I follow any tradition, it is his.” If Beckett’s guilty souls are trapped in endless, Dantesque hells, it’s Johnson’s spirit they often blindly, unwittingly stumble after: “You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

For what it’s worth, Mr. Bate’s “Samuel Johnson” was a rare triple-crown prize-winner: the NBCC, the National Book Award and the Pulitzer (Mr. Bate’s second Pulitzer; his first was for his life of Keats). More tellingly, perhaps: Since Mr. Bate’s life first appeared, scholars have pried away various pieces of Johnson and Boswell for closer, rewarding examination — as with Mr. Sisman’s “Boswell’s Presumptuous Task” or Charlies Pierce’s “The Religious Life of Samuel Johnson.” But in those 30 years, no one has written a biography of the great man that can touch it.

—Jerome Weeks is a long-time NBCC member, former book critic of the Dallas Morning News, and host of the Artsjournal.com book blog,bookdaddy.