NBCC members: If you’d like to contribute a review of an eligible book for the 2020 Leonard Prize, write to NBCC board member Megan Labrise at labrise@gmail.com. Read the rest of the reviews here.

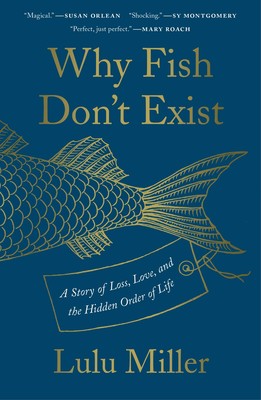

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life by Lulu Miller (Simon & Schuster)

Why Fish Don’t Exist is an extraordinary book, a wild mix of science writing, biography, love story, and memoir. Beautifully written, it is also a meditation on the things that matter in life. It amply deserves consideration for the 2020 John Leonard Prize.

Fans of public radio will know Lulu Miller as the co-creator of Invisibilia and the co-host of Radiolab. Why Fish Don’t Exist is her first book, and it’s also the first book I have read that manages to be (and do) so many things at once. On the most obvious level, Miller interweaves a raw account of her own troubled attempts to make sense of a world her scientist-father had taught her was meaningless with the biography of a long-dead scientist, Stanford University’s founding president David Starr Jordan (1851-1931). A world-renowned ichthyologist, Jordan seemed to radiate all those qualities which Miller, who came close to taking her own life at one point, found woefully absent in herself: charisma, optimism, the certainty that the universe is entirely knowable, just waiting to be figured out by the qualified scientist.

Exhilarated by the fact of his own unquestionable importance to the world, Jordan celebrated his achievements in his 1,600-page autobiography, which Miller acquired and dutifully studied, growing steadily disenchanted not only with the man but also the science he advocated. Some of the most incisive pages of Why Fish Don’t Exist grapple with taxonomy, Jordan’s unwavering confidence that all living things can be named and slotted into place. Buoyed by modern evolutionary insights, Miller decides that “fish,” as a category, really don’t exist—the term hides nuance, denies intelligence, and creates “a false sense of separation to preserve our spot at the top of an imaginary ladder.” As far as Miller is concerned, there’s only this fish or that fish—individuals, rich in their unique, unfathomable, shimmering, unclassifiable beauty. This realization allows Miller to confront the most dismal part of Jordan’s legacy, his belief in eugenics, which she insists is an integral component of his static view of science, not an aberration. In what I think is the emotional heart of the book, Miller visits Anna, sterilized decades ago at the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, who is now “living the hell out of a life” that eugenicists like Jordan didn’t want her to have. (Committees at Stanford and Harvard University took note of Miller’s book when they recently recommended that Jordan’s name be removed from campus buildings.)

Her meeting with Anna, rendered in searing detail, liberates Miller to live the hell out of her own life, too. Abandoning her unreciprocated love for an unnamed, “cinnamon-scented” male, she embarks on a relationship with the emerald-eyed woman who is now her wife. In the final, irresistible cameo of Miller’s literary debut, we see the author snorkeling with her new lover in Tobacco Bay, Bermuda, gliding through the clear waters, surrounded not by “fish” but this fish and that fish and that fish, a world filled with living beings of all kinds, luminous with possibility.