Critical Mass occasionally asks critics to name five books that should be in any reviewer's library. Herewith is Lorin Stein's response.

Critical Mass occasionally asks critics to name five books that should be in any reviewer's library. Herewith is Lorin Stein's response.

If you are (or want to be) a critic, then sometimes I think it's good to ask what criticism is for. The first book that made me do that was Susan Sontag's Against Interpretation. “We need an erotics, not a hermeneutics, of art.” I was sitting after school in a Swensen's ice cream parlor when I read that. I had to go home and look up the word hermeneutics. But the reviews gave one the gist. This was criticism as seduction. Sontag could make a semi-literate fifteen-year-old want to read Michel Leiris or Samuel Beckett or see a Godard film. She made it all seem both glamorous and accessible–which are things I still feel art should be.

In college, reversing the normal course of things, I came to worship Edmund Wilson, whose first collection, Axel's Castle: The Imaginative Literature of 1870–1930, explained the works of Joyce, Stein, Eliot & Co. by tracing their roots back to the fin de siècle. Explaining gets a bad rap, but Wilson's explanations were also seductions. His books gave me the idea that a critic's first job was to describe complex works in the simplest possible terms. He implied a common reader who really appealed to me. I remember reading Julia Kristeva in college–with Wilson in my head–and thinking, not simply that I missed his prose, but that I missed his reader too.

My other critic-hero in college was D.H. Lawrence. Harold Bloom claims that Lawrence's essay on Whitman, in Studies in Classic American Literature, is the best thing on Whitman ever written. I wouldn't know–it certainly blew my mind. Among other things, it gave me the idea that a critic should write out of anger and love–that love was a problem, perhaps the problem, to be addressed. And that if you have something to say as a critic, you must (in Lawrence's words) say it hot. The sentences were a revelation. Studies is the only book of criticism that I have asked to hear read aloud. I think it is the book I have given most often as a present.

My favorite contemporary book of criticism is Vivian Gornick's collection The End of the Novel of Love. To me that book and Studies make a diptych–both are basically concerned with what Gornick calls “love as metaphor.” I read The End of the Novel of Love in my twenties–twice, in the space of a day. Since then I have never written an essay that wasn't, deeply and superficially, indebted to Gornick. For years I tried to model my sentences on hers. My sense of criticism–that it must tell a story, that the story must be true, that the story must unlock a secret in the critic's own inner life–I owe entirely to her example. Whenever a reader points out the similarity of my approach (and my prose) to hers, it is the praise that pleases me most.

David Foster Wallace disowned any debt to his old philosophy teacher Stanley Cavell. To my ear, Cavell's later work is a forerunner to Infinite Jest. It has the sound of a mind questing in plain language, through elaboration and elaboration, to say what it simply knows. Cavell's essay “The Avoidance of Love”–ostensibly a study of embarrassment in King Lear–poses the great paradox of all criticism: that the critic must say what is obvious, what is right there in the text, but must show that every previous critic has ignored it or got it wrong. For that essay, and for his movie criticism, my short shelf would have to include The Cavell Reader, though I hesitate to recommend it above a book like Hugh Kenner's study of British modernism, A Sinking Island; or above Henry Green's memoir, Pack My Bag, which I read continually for encouragement; or above the unmatched poetry criticism of Randall Jarrell; or above William Hazlitt or George Orwell or Richard Poirier or August Kleinzahler's Music I-LXXIV–a book that I keep shoving under people's noses, simply because it beggars description. I also have to mention Dave Hickey's Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy, because I read it last week, and can feel it working on me now. But the assignment calls for five recommendations, and those first five are the ones that for better or worse formed my sense of the job.

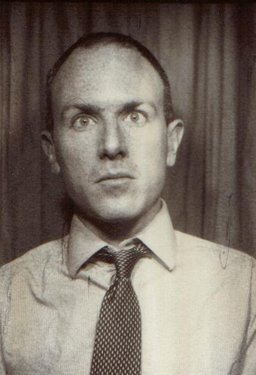

Lorin Stein is the editor of The Paris Review. His reviews have appeared in The New York Review of Books, Harper's, and other magazines.