After an overnight in Youngstown, Ohio (shoutout to the incredible cast and crew at Station Square restaurant), I’m thinking about the Monongahela Valley and the coming of a new underclass in the 1980s (well, I’m also thinking of Bruce Springsteen’s “Youngstown”):

From the Monongahela valley to the Mesabi iron range

To the coal mines of Appalachia, the story’s always the same

Seven hundred tons of metal a day, now sir you tell me the world’s changed

Once I made you rich enough, rich enough to forget my name

After hours of driving in torrential rains through the gentle mountains that lead eventually to the Poconos, and finally to the urban sprawl that has obscured much of the natural terrain of the Eastern seaboard, I’m drawn in two directions.

First the literature of the white working class folks who fell off the working map in the last part of the twentieth century, small town folk, holler folk. Sherwood Anderson wrote about this place generations ago in Winesburg, Ohio, first published in 1919. Among his characters, an “old man,” a writer who, based on dreams, creates “The Book of the Grotesques.” ” The grotesques were not all horrible. Some were amusing, some almost beautiful, and one, a woman all drawn out of shape, hurt the old man by her grotesqueness.”

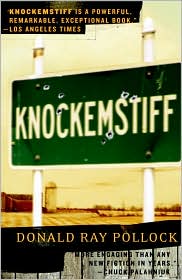

And former paper mill worker Donald Ray Pollock portrayed folks living in extremity in dying towns in Ohio in a story collection set in his hometown called “Knockemstiff,” published last year. I was in the audience last fall when Pollock won the PEN/Robert Bingham award. He thanked his wife, a school teacher, who could not be there that night (she was working). Pollock grew up in Knockemstiff. Ohio, after working for many years went back for an MFA at Ohio State. His collection is a raw, bruised, unflinching look at holler life from the 1960s into this century. (Pollock’s website includes audio of a chat with Chuck Palahniuk, which gives some sense of his influences.) Jonathan Miles in the New York Times compared “Knockemstiff” to “Winesburg, Ohio.”

The AP sent a reporter to an Ohio reading he did and reported that ” locals hold no grudges against author Donald Ray Pollock for depicting life here as a grotesque blend of drug abusers, wife beaters and sex fiends.”

Esquire called its excerpt from his story “Discipline” “the 96 least nurturing words published this month”

This excerpt from his story “Real Life” got my goat at first (guess why?)

My father showed me how to hurt a man one august night at the Torch Drive-in when I was seven years old. It was the only thing he was ever any good at. This was years ago, back when the outdoor movie experience was still a big deal in southern Ohio. Godzilla was playing, along with some sorry-ass flying saucer movie that showed how pie pans could take over the world.

It was hotter than a fat lady’s box that evening, and by the time the cartoon began playing on the big plywood screen, the old man was miserable. He kept bitching about the heat, sopping the sweat off his head with a brown paper bag. Ross County hadn’t had any rain in two months. Every morning my mother turned the kitchen radio to KB98 and listened to Miss Sally Flowers pray for a thunderstorm. Then she’d go outside and stare at the empty white sky that hung over the holler like a sheet. Sometimes I still think about her standing in that brittle brown grass, stretching her neck in hopes of seeing just one lousy dark cloud.

Okay, I reminded myself of time spent in Butte, Montana, a tough mining town where no one minces words, and in newspaper offices, ditto. Now Pollock is working on a novel about a serial killer. And there will be lots of attention on that when he finishes it.

Second direction, August Wilson’s astonishing play cycle about the African-American community of Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Listening to the radio while driving I-80 through those mountains, I heard a group of kids from the Hill District, reading their winning essays about heroes—their single moms or grandmothers. And there was a reference to the Hill District branch of the Carnegie Library.

August Wilson! The late great should have won a Nobel August Wilson.All but one of the ten plays in his 20th century cycle are set in the Hill District. His first Hill District play, on Broadway in 1987, was “Fences,” set in the 1950s. Frank Rich review here.

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” set in the early 20th century, was revived on Broadway this past May.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has covered Wilson’s work more fully than any newspaper, regularly interviewing him; theater critic Christopher Rawson has chronicled his work and regularly reviewed his plays (see links including his speeches in Pittsburgh here).

The Post-Gazette timeline of his life here:

In 1999, when Wilson was at the top of the list of Pittsburgh power brokers, he spoke at the 100th anniversary of the Hill District branch of the Carnegie Library on Wylie Avenue, described getting his first library card there in 1950. “It was on these streets in this community in this city that I came into manhood and I have a fierce affection for the Hill District and the people who raised me, who have sanctioned my life and ultimately provide it with its meaning,” he said. Years later, he returned and pulled off the shelf a book called “The Invisible Man.” He described the impact:

“It opened a world that I entered and have never left. I have for years been promising myself a second reading, as an adult and a much more experienced reader, but I continually forestall it because I do not want to abandon the magical and mystifying memory of that first reading.

“If I have not read ‘The Invisible Man’ again, I have read the poems of Langston Hughes over and over. They stand as timeless texts that are seminal to our experience in what the Hon. Elijah Muhammad called ‘the wilderness of North America.’

“It was only after reading Langston Hughes’s ‘Mother to Son’ that I realized my mother might have had a life outside my consciousness with a history and aspirations which I knew nothing about. All of these things as a 14-year-old kid, who because he weighed 175 pounds and was nearly as big as Floyd Patterson, wanted to be the heavyweight champion of the world for two months and Hank Aaron the next two.

“The thing that was constant was that shelf in the library with those 30 or so odd books from which, after I read them and was preparing to move on, I took a lot of new ideas and discoveries about myself and what life as an adult could possibly mean and how it might possibly be lived.

“But one thing I took beyond all others that that shelf of books gave me was the proof that it was possible to be a writer.”

And a last thought, as I slide back into the urban sprawl. In these unprecedented times, as the economy reels and book culture absorbs more shocks than we can yet count, we still need each new generation to read, to dream, to imagine being writers—and readers. Let’s not disenfranchise those future writers and readers without the means to purchase highspeed internet, Kindles, iPods, and the lot. And let’s keep open those all-important libraries, which lend books and offer internet access. And hope.