Driving from eastern Wyoming’s arid 9000-foot Rocky Mountain plateau to the humid green expanse of western Nebraska creates a sort of culture shock. Five hundreds miles in Europe would mean a trip through multiple boundaries, EU be damned. Here, when the altitude drops 5,000 feet within a matter of hours, tumbleweeds give way to fields of sunflowers, then thousands of acres of corn, and a smattering of hay, and the sounds of locusts fills the air along the sparkling Platte River, with lush green borders. The shift is geographic, organic, natural, not to mention cultural.

Willa Cather, of Red Cloud, Nebraska, captured the high plains well in “My Antonia,” first published in 1918. Her young narrator, recently orphaned, arrives by covered wagon at night and marvels at the expanse before him: “There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made. No, there was nothing but land-slightly undulating, I knew, because often our wheels ground against the brake as we went down into a hollow and lurched up again on the other side. I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man’s jurisdiction. I had never before looked up at the sky when there was not a familiar mountain ridge against it. But this was the complete dome of heaven, all there was of it. I did not believe that my dead father and mother were watching me from up there; they would still be looking for me at the sheepfold down by the creek, or along the white road that led to the mountain pastures. I had left even their spirits behind me. The wagon jolted on, carrying me I knew not whither. I don’t think I was homesick. If we never arrived anywhere, it did not matter. Between that earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out. I did not say my prayers that night: here, I felt, what would be would be.”

It’s easy to feel transplanted back to another time on this drive through the passes where the pioneers once traveled on horseback, or in covered wagons. Settling into a motel in Kearney, I turned to Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” and found his historic parallel: “At 2 P.M. the belt of timber that fringes the North Platte and marks its windings through the vast level floor of the Plains came in sight. At 4 P.M. we crossed a branch of the river, and at 5 P.M. we crossed the Platte itself, and landed at Fort Kearney.”

And then there is Terese Svoboda, Nebraska born (in Ogallala, a destination for countless cattle drives in frontier days), prolific and protean author, who said recently, when asked, Who let you take up writing? “Creative writing offered itself as an option to analyzing texts, which I found hard to do, as easily seduced I was with words. I never believed writers or artists pre-visualized the symbols or the interweavings or they’d never made their art in the first place. Art is all about energy, not exhaustion. Given permission, I wrote furiously in my youth and also painted, sculpted, and made movies. It was also the seventies when everyone was an artist. When the great wash of peers pulled back and it was revealed that they had secretly studied law or medicine, there I was, standing in the sand, still making art. I never questioned this stance and I was lucky to have had teachers who believed making art was as necessary as banking. However, my dad still wants me to sell real estate.”

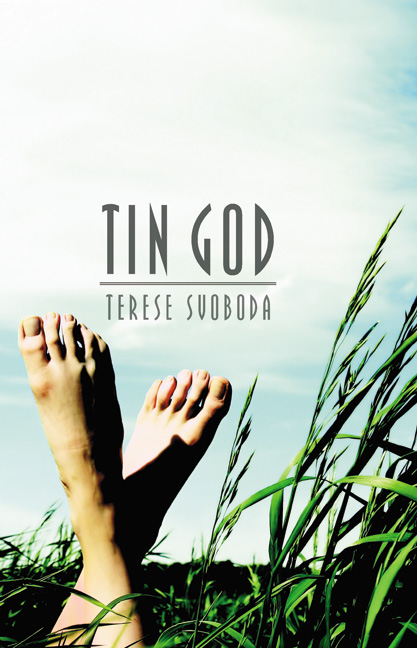

Svoboda’s “Black Glasses like Clark Kent” won last year’s Graywolf nonfiction award. I’ve put her novel “Tin God” on my to-read list.